B'nai Jacob Synagogue | |

| |

| |

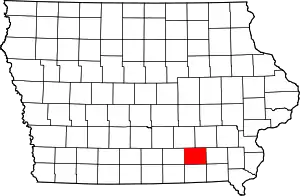

| Location | 529 E. Main Street, Ottumwa, Iowa |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°0′50.3″N 92°24′24.8″W / 41.013972°N 92.406889°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1915 |

| Built by | L.T. Chrisman, and Co. |

| Architect | George M. Kerns |

| Architectural style | Renaissance[1] or Deco Vernacular[2] |

| MPS | Ottumwa MPS |

| NRHP reference No. | 04000815[3] |

| Added to NRHP | August 10, 2004[3] |

B'nai Jacob Synagogue is a former Conservative synagogue in Ottumwa, Iowa. The originally Orthodox congregation was established in 1898, and it constructed the E. Main Street synagogue building in 1915, and joined the Conservative movement in the 1950s.

The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2004. The synagogue closed as apace of worship in 2010 and the building is now preserved as a meeting and performance space.

History

The first Jewish settlement in Ottumwa in the 19th century was dominated by German Jews, and in the early 1880s, there was an organized German congregation. By 1884, this had dissolved as most of the original German pioneers died out and their children left town. In 1886 there were about 20 Jewish families in town.[4] The Ottumwa Jewish cemetery, founded by the Ottumwa Hebrew Association in 1876, was the lasting legacy of this period of Ottumwa's history.[5]

Edna Ferber lived in Ottumwa as a child in the 1890s. Her father operated The Fair, an Ottumwa department store. At the time, Ottumwa was a coal mining town, and the antisemitism of the town had a lasting influence on Ferber. She wrote of her years in Ottumwa: "I don't think that there was a day when I wasn't called a sheeny."[6][7]

By the turn of the 20th century, Ottumwa had fewer than 50 Jewish families, immigrants from Germany and across eastern Europe. Most were "in the junk and second-hand business", but there were also laborers, shoemakers, tailors and one prominent merchant. Some families were extremely observant, "wearing two types of phylacteries", while others believed "in no Judaism at all." One local Jew had a personal Torah scroll and a private mikvah, but there was no organized community.[8]

In the early 1900s, many people called the area around the 300, 400 and 500 blocks of Main Street "Jew Town" because the stores in the neighborhood were mostly owned by Jewish families, many of whom lived above their stores.[9] The B'nai Jacob congregation was organized in 1898. In 1907, the congregation was located at 404 E. Main St., and had 15 members out of an estimated Jewish population of 150. The Hebrew school had 15 pupils and met once per week. By 1919, the Jewish population of Ottumwa had risen to 412 and the congregation had moved one block into the current building. The school still only had one teacher on staff, but there were 21 pupils and the school met daily.[5][10] The B'nai Jacob congregation numbered around 250 in the 1930s and 1940s. The synagogue affiliated with the Conservative movement in the 1950s.

The Jewish population of Ottumwa was 231 in 1951.[11] By 1960, the Jewish population was estimated at 175,[12] and by 1962, 150.[13] For the next two decades, through 1983, the population estimate remained unchanged.[14][15][16] By 2010, the congregation on a typical Saturday morning had shrunk to seven or so, and by 2018, as few as two.[9][17][18] In August of that year, the congregation donated its Torah scroll "to a new synagogue forming in South America", and ceased functioning.[19]

Building

B'nai Jacob's Renaissance[1] or Deco Vernacular[2] synagogue building at 529 East Main Street (at Union Street) was constructed in 1915. The architect was George M. Kerns and L.T. Chrisman and Company was the contractor. The exterior is brick, with an addition in the back holding a kitchen and social hall, built some time in the 1950s.

As originally built, the bimah was in the center of the sanctuary, but in an earlier modernization of the building, the central bimah was removed. The woodwork around the Torah ark is original, as is the 7-branched menorah in front of the ark. The ark doors and interior, however, are not original.

The sanctuary features a woman's gallery against the south-west wall, built over the front entrance foyer and classroom, although it is rarely used. In traditional Judaism, women were seated separately from men, separated by a mechitza which frequently took the form of a balcony. The separation of men and women at B'nai Jacob ended when one woman's health problems prevented her from climbing the stairs to the balcony.

The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on August 10, 2004 (reference number 4000815),[3] and underwent major historic restoration in 2004–2005.[9][17]

In February 2019 the building was donated to the American Gothic Performing Arts Festival and renamed Temple of Creative Arts, to be used as meeting and performance space.[19]

References

- 1 2 "B'Nai Jacob Synagogue, Ottumwa Iowa". Archiplanet. December 5, 2010. Archived from the original on May 27, 2009.

- 1 2 Preisler, Julian H. (2007–2010). "Congregation B'Nai Jacob". American Synagogues, A Photographic Journey. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010.

- 1 2 3 NRHP Weekly list, August 20, 2004

- ↑ Goldenberg, Bertha (June 1886). "The Sabbath Visitor: Letter". Cincinnati. p. 127.

- 1 2 Szold, Henrietta, ed. (1907). "American Jewish Yearbook 5668". Ottumwa: Jewish Publication Society. p. 180.

- ↑ Watts, Eileen H.; Avery, Edna Ferber (2007). "Jewish American Writer: Who Knew?". In Avery, Evelyn Gross (ed.). Modern Jewish Writers in America. pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Lemberger, Michael W.; Michaels, Leigh (2007). Ottumwa. Arcadia. p. 40. ISBN 9780738550831.

- ↑ Glazer, Simon (1904). "Ottumwa". The Jews in Iowa. Des Moines: Koch Brothers. pp. 314–315. ISBN 9780722247921.

- 1 2 3 "B'nai Jacob Synagogue in Ottumwa Turns 90". Ottumwa Courier. September 13, 2005. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ↑ Schneiderman, Harry, ed. (1919). "Ottumwa". American Jewish Yearbook 5680. Vol. 21. Jewish Publication Society. p. 374.

- ↑ Fine, Morris, ed. (1951). "Jewish Population Estimates" (PDF). American Jewish Yearbook. Jewish Publication Society of America. p. 18.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Erich (1963). "Studies of Jewish Intermarriage in the United States" (PDF). American Jewish Yearbook. American Jewish Committee. p. 35.

- ↑ Fine, Morris; Himmelfarb, Milton, eds. (1963). "American Jewish Yearbook: Appendix" (PDF). American Jewish Committee. p. 71.

- ↑ Jelenko, Martha; Fine, Morris; Hillelfarb, Milton, eds. (1973). "American Jewish Yearbook: Appendix" (PDF). Jewish Publication Society. p. 311.

- ↑ Jelenko, Martha; Fine, Morris; Hillelfarb, Milton, eds. (1976). "American Jewish Yearbook: Appendix" (PDF). American Jewish Committee. p. 234.

- ↑ Hillelfarb, Milton; Singer, David, eds. (1984). "American Jewish Yearbook: Appendix" (PDF). American Jewish Committee. p. 168.

- 1 2 Buhrman, Matt (July 6, 2010). "Historic Places: B'Nai Jacob Synagogue". Kirksville, Missouri/Ottumwa, Iowa: KTVO.

- ↑ "Dwindling membership challenges Ottumwa synagogue". Ottumwa Courier. May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- 1 2 Milner, Matt (June 17, 2019). "Performing arts festival celebrates new home", Ottumwa Courier.

External links

- B'nai Jacob Synagogue, Facebook