| Adhan | |

| Arabic | أَذَان |

|---|---|

| Romanization | aḏān, athan, azaan, adhaan, athaan |

| Literal meaning | Call to the prayer |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

Adhan (Arabic: أَذَان [ʔaˈðaːn]), also variously transliterated as athan, adhane (in French),[1] ajan/ajaan, azan/azaan (in South Asia), adzan (in Southeast Asia), and ezan (in the Balkans and Turkey), among other languages,[2] is the Islamic call to public prayer (salah) in a mosque recited by a muezzin at prescribed times of the day.

Adhan is recited from the mosque five times daily, traditionally from the minaret. It is the first call summoning Muslims to enter the mosque for obligatory (fard) prayer (salah). A second call, known as the iqamah, summons those within the mosque to line up for the beginning of the prayers. Only in Turkey, Ezan is voiced in five different styles at different times; saba, uşşak, hicaz, rast, segah.[3]

Terminology

Adhān, Arabic for "announcement", from root ʾadhina meaning "to listen, to hear, be informed about", is variously transliterated in different cultures.[1][2]

It is commonly written as athan, or adhane (in French),[1] azan in Iran and south Asia (in Persian, Dari, Pashto, Hindi, Bengali, Urdu, and Punjabi), adzan in Southeast Asia (Indonesian and Malaysian), and ezan in Turkish and Serbo-Croatian Latin (езан in Serbo-Croatian Cyrillic and Bulgarian, ezani in Albanian).[2] Muslims on the Malabar Coast in India use the Persian term بانگ, banku, for the call to public prayer.[4]

Another derivative of the word adhān is ʾudhun (أُذُن), meaning "ear".

Announcer

The muezzin (Arabic: مُؤَذِّن muʾaḏḏin) is the person who recites the adhan[5][6]: 470 from the mosque. Typically in modern times, this is done using a microphone:[7] a recitation that is consequently broadcast to the speakers usually mounted on the higher part of the mosque's minarets, thus calling those nearby to prayer. However, in many mosques, the message can also be recorded. This is due to the fact that the "call to prayer" has to be done loudly and at least five times a day. This is usually done by replaying previously recorded "call to prayer" without the presence of a muezzin. This way, the mosque operator has the ability to edit or mix the message and adjust the volume of the message while also not having to hire a full-time muezzin or in case of the absence of a muezzin. This is why in many Muslim countries, the sound of the prayer call can be exactly identical between one mosque and another, as well as between one Salah hour and another, as is the case for the London Central Mosque. In the event of a religious holidays like Eid al-Fitr, for example in Indonesia, where the Kalimah (speech) has to be recited out loud all day long, mosque operators uses this recording method to create a looping recital of the Kalimah.

The muezzin is chosen for his ability in reciting the adhan clearly, melodically, and loudly enough for all people to hear. This is one of the important duties in the mosque, as his companions and community rely on him in his call for Muslims to come to pray in congregation.[8] The Imam leads the prayer five times a day. The first muezzin in Islam was Bilal ibn Rabah, a freed slave of Abyssinian heritage.[9][10]

Words

| Recital | Arabic Qurʾanic Arabic |

Transliteration | Translation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunni | Shia | Quranist | |||||||

| Hanafi | Maliki | Shafi'i | Hanbali | Imami | Zaydi | ||||

| 4x | 2x | 4x | 2x | ٱللَّٰهُ أَكْبَرُ | ʾAllāhu ʾakbaru | God is the Greatest | |||

| 2x | أَشْهَدُ أَن لَّا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ | ʾašhadu ʾan lā ʾilāha ʾillā -llāhu | I testify There is no deity but God | ||||||

| 2x | None | أَشْهَدُ أَنَّ مُحَمَّدًا رَسُولُ ٱللَّٰهِ | ʾašhadu ʾanna Muḥammad al rasūlu -llāhi | I testify Muhammad is the Messenger of God | |||||

| None | 2x (Mustahabb) | None | أَشْهَدُ أَنَّ عَلِيًّا وَلِيُّ ٱللَّٰهِ | ašhadu ʾanna ealyaaan wally -llāh | I testify Ali is the Vali (vicegerent) of God | ||||

| 2x | حَيَّ عَلَى ٱلصَّلَاةِ حَيَّ عَلَى ٱلصَّلَوٰةِ |

ḥayya ʿalā ṣ-ṣalāhti | Hasten to the prayer (Salah) | ||||||

| 2x | حَيَّ عَلَى ٱلْفَلَاحِ حَيَّ عَلَى ٱلْفَلَٰحِ |

ḥayya ʿalā l-falāḥi | Hasten to the salvation | ||||||

| None | 2x | None | حَيَّ عَلَىٰ خَيْرِ ٱلْعَمَلِ | ḥayya ʿalā khayri l-ʿamali | Hasten to the best of deeds | ||||

| 2x (Fajr prayer only)[lower-alpha 1] |

None | ٱلصَّلَاةُ خَيْرٌ مِنَ ٱلنَّوْمِ ٱلصَّلَوٰةُ خَيْرٌ مِنَ ٱلنَّوْمِ |

aṣ-ṣalātu khayrun mina n-nawmi | Prayer is better than sleep | |||||

| 2x | ٱللَّٰهُ أَكْبَرُ | ʾAllāhu ʾakbaru | God is the Greatest | ||||||

| 1x | 2x | 1x | لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ | lā ʾilāha ʾillā -llāhu | There is no deity but God | ||||

On rare occasions, the muezzin may say 'Sallu fi buyutikum (Pray in your homes) or Sallu fi rihaalikum (Pray in your dwellings) if it is raining heavily, if it is windy or if it is cold. Another case where this was said was during the COVID-19 lockdown. The phrase is usually said at the end of the adhan or he may skip Hayya ala salah and Hayya alal falah; other ways have also been narrated.

Religious views

Sunni

| External videos | |

|---|---|

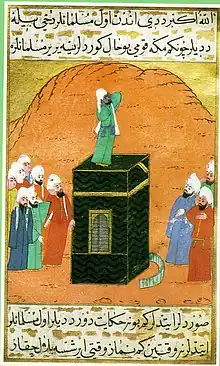

Sunnis state that the adhan was not written or said by the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, but by one of his Sahabah (his companions). Abdullah ibn Zayd, a sahabi of Muhammad, had a vision in his dream, in which the call for prayers was revealed to him by God. He later related this to his companions. Meanwhile, this news reached Muhammad, who confirmed it. Because of his stunning voice Muhammad chose a freed Habeshan slave by the name of Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi to make the call for prayers. Muhammad preferred the call better than the use of bells (as used by the Christians) and horns (as by the Jews).[11][12][13]

During the Friday prayer (Salat al-Jumu'ah), there is one adhan but some Sunni Muslims increase it to two adhans; the first is to call the people to the mosque, the second is said before the Imam begins the khutbah (sermon). Just before the prayers start, someone amongst the praying people recites the iqama as in all prayers. The basis for this is that at the time of the Caliph Uthman he ordered two adhans to be made, the first of which was to be made in the marketplace to inform the people that the Friday prayer was soon to begin, and the second adhan would be the regular one held in the mosque. Not all Sunnis prefer two adhans as the need for warning the people of the impending time for prayer is no longer essential now that the times for prayers are well known.

Shia

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Shia sources state Muhammad, according to God's command, ordered the adhan as a means of calling Muslims to prayer. Shia Islam teaches that no one else contributed, or had any authority to contribute, towards the composition of the adhan.[11][12][14]

Shia sources also narrate that Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi was, in fact, the first person to recite the adhan publicly out loud in front of the Muslim congregation.

The fundamental phrase lā ʾilāha ʾillā llāh is the foundation stone of Islam along with the belief in it. It declares that "there is no god but the God". This is the confession of Tawhid or the "doctrine of Oneness [of God]".

The phrase Muḥammadun rasūlu -llāh fulfills the requirement that there should be someone to guide in the name of God, which states Muhammad is God's Messenger. This is the acceptance of prophethood or Nabuwat of Muhammad.

Muhammad declared Ali ibn Abi Talib as his successor, at Ghadir Khumm, which was required for the continuation of his guidance. According to the hadith of the pond of Khumm, Muhammad stated that "Of whomsoever I am the authority, Ali is his authority". Hence, it is recommended to recite the phrase ʿalīyun walī -llāh ("Ali is His [God's] Authority").

In one of the Qiblah of Ma'ad al-Mustansir Billah (1035–1094) of Fatemi era masjid of Qahira (Mosque of Ibn Tulun) engraved his name and kalimat ash-shahādah as lā ʾilāha ʾillā -llāh, muḥammadun rasūlu -llāh, ʿalīyun walīyu -llāh (لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ مُحَمَّدٌ رَسُولُ ٱللَّٰهِ عَلِيٌّ وَلِيُّ ٱللَّٰهِ).

Adhan reminds Muslims of these three Islamic teaching Tawhid, Nabuwat and Imamate before each prayer. These three emphasise devotion to God, Muhammad and Imam, which are considered to be so linked together that they can not be viewed separately; one leads to other and finally to God.

The phrase is optional to some Shia as justified above. They feel that Ali's Walayah ("Divine Authority") is self-evident, a testification and need not be declared. However, the greatness of God is also taken to be self-evident, but Muslims still declare Allāhu ʾakbar to publicize their faith. This is the reason that the most Shia give for the recitation of the phrase regarding Ali.

Dua (supplication)

Sunni

While listening to the adhan, Sunni Muslims repeat the same words silently, except when the adhan reciter (muezzin) says: "حَيَّ عَلَى ٱلصَّلَاةِ" or "حَيَّ عَلَى ٱلْفَلَاحِ" (ḥayya ʿalā ṣ-ṣalāhti or ḥayya ʿala l-falāḥi)[15] they silently say: "لَا حَوْلَ وَلَا قُوَّةَ إِلَّا بِٱللَّٰهِ" (lā ḥawla wa lā quwwata ʾillā bi-llāhi) (there is no strength or power except from God).[16]

Immediately following the adhan, Sunni Muslims recite the following dua (supplications):

1. A testimony:

وَأَنَا أَشْهَدُ أَنْ لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ وَحْدَهُ لَا شَرِيكَ لَهُ وَأَنَّ مُحَمَّدًا عَبْدُهُ وَرَسُولُهُ رَضِيتُ بِٱللَّٰهِ رَبًّا وَمُحَمَّدٍ رَسُولًا وَبِٱلْإِسْلَامِ دِينًا

wa-ʾanā ʾašhadu ʾan lā ʾilāha ʾillā llāhu waḥdahu lā šarīka lahu wa-ʾanna muḥammadan ʿabduhu wa-rasūluhu, raḍītu bi-llāhi rabban wa-bi-muḥammadin rasūlan wa-bi-lʾislāmi dīnān

"I bear witness that there is no deity but God alone with no partner and that Muhammad is His servant and Messenger, and the Lord God's chosen messenger is Muhammad and Islam is his religion."[17]

2. An invocation of blessings on Muhammad:

ٱللَّٰهُمَّ صَلِّ عَلَىٰ مُحَمَّدٍ وَعَلَىٰ آلِ مُحَمَّدٍ كَمَا صَلَّيْتَ عَلَىٰ إِبْرَاهِيمَ وَعَلَىٰ آلِ إِبْرَاهِيمَ إِنَّكَ حَمِيدٌ مَجِيدٌ ٱللَّٰهُمَّ بَارِكْ عَلَىٰ مُحَمَّدٍ وَعَلَىٰ آلِ مُحَمَّدٍ كَمَا بَارَكْتَ عَلَىٰ إِبْرَاهِيمَ وَعَلَىٰ آلِ إِبْرَاهِيمَ إِنَّكَ حَمِيدٌ مَجِيدٌ

ʾallāhumma ṣalli ʿalā muḥammadin wa-ʿalā ʾāli muḥammadin, kamā ṣallayta ʿalā ʾibrāhīma wa-ʿalā ʾāli ʾibrāhīma, ʾinnaka ḥamīdun majīd. ʾallāhumma bārik ʿalā muḥammadin wa-ʿalā ʿalā muḥammadin, kamā bārakta ʿalā ʾibrāhīma wa-ʿalā ʾāli ʾibrāhīma ʾinnaka ḥamīdun majīdun

"O God, sanctify Muhammad and the Progeny of Muhammad, as you have sanctified Ibrahim and the Progeny of Ibrahim. Truly, You are Praised and Glorious. O God, bless Muhammad and the Progeny of Muhammad, as you have blessed Ibrahim and the Progeny of Ibrahim. Truly, You are Praised and Glorious."[18]

3. Muhammad's name is invoked requested:

اللَّهُمَّ رَبَّ هَذِهِ الدَّعْوَةِ التَّامَّةِ وَالصَّلاَةِ الْقَائِمَةِ آتِ مُحَمَّدًا الْوَسِيلَةَ وَالْفَضِيلَةَ وَابْعَثْهُ مَقَامًا مَحْمُودًا الَّذِي وَعَدْتَه

ʾAllahumma Rabba hadhihid-da`watit-tammah, was-solatil qa'imah, ati Muhammadan-l-wasilata wal-fadilah, wa-b`ath-hu maqaman mahmudan-il-ladhi wa`adtahuū

"O Allah! Lord of this perfect call (perfect by not ascribing partners to You) and of the regular prayer which is going to be established, give Muhammad the right of intercession and illustriousness, and resurrect him to the best and the highest place in Paradise that You promised him (of)."

4. Dua are then made directly to God, between the adhan and the iqamaah.

According to Abu Dawud, Muhammad said: "Repeat the words of the mu'azzin and when you finish, ask God what you want and you will get it".[20]

Shia

While listening to the adhan, Shia Muslims repeat the same words silently, except when the adhan reciter (muezzin) says: "أَشْهَدُ أَنْ لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ" and "أَشْهَدُ أَنَّ مُحَمَّدًا رَسُولُ ٱللَّٰهِ" (ʾašhadu ʾan lā ʾilāha ʾillā -llāhu and ʾašhadu ʾanna Muḥammadan rasūlu -llāhi) they silently say:

وَأَنَا أَشْهَدُ أَنْ لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ وَأَشْهَدُ أَنَّ مُحَمَّدًا رَسُولُ ٱللَّٰهِ (صَلَّى ٱللَّٰهُ عَلَيْهِ وَآلِهِ وَسَلَّمَ) أَكْتَفِي بِهَا عَمَّنْ أَبَىٰ وَجَحَدَ وَأُعِينُ بِهَا مَنْ أَقَرَّ وَشَهِدَ

wa-ʾanā ʾašhadu ʾan lā ʾilāha ʾillā -llāhu wa-ʾašhadu ʾanna muḥammadan rasūlu -llāhi (ṣallā -llāhu ʿalayhi wa-ʾālihi wa-sallama) ʾaktafī bihā ʿamman ʾabā wa-jaḥada wa-ʾuʿīnu bihā man ʾaqarra wa-šahida

"And I [also] bear witness that there is no deity but God, I bear witness that Muhammad is the Messenger of God, and I suffice by it (the testimonies) against whoever refuses and fights against it (the testimonies), and I designate by it one who agrees and testifies."[21]

Whenever Muhammad's name is mentioned in the adhan or Iqama, Shia Muslims recite salawat,[22] a form of the peace be upon him blessing specifically for Muhammad. This salawat is usually recited as either ṣallā -llāhu ʿalayhī wa-ʾālihī wa-sallama (صَلَّى ٱللَّٰهُ عَلَيْهِ وَآلِهِ وَسَلَّمَ), ṣallā -llāhu ʿalayhī wa-ʾālihī (صَلَّى ٱللَّٰهُ عَلَيْهِ وَآلِهِ), or ʾallāhumma ṣalli ʿalā muḥammadin wa-ʾāli muḥammadin (ٱللَّٰهُمَّ صَلِّ عَلَىٰ مُحَمَّدٍ وَآلِ مُحَمَّدٍ).

Immediately following the adhan, Shia Muslims sit and recite the following dua (supplication):

ٱللَّٰهُمَّ ٱجْعَلْ قَلْبِي بَارًّا وَرِزْقِي دَارًّا وَٱجْعَلْ لِي عِنْدَ قَبْرِ نَبِيِّكَ (صَلَّى ٱللَّٰهُ عَلَيْهِ وَآلِهِ وَسَلَّمَ) قَرَارًا وَمُسْتَقَرًّا

ʾallāhumma -jʿal qalbī bārran wa-rizqī dārran wa-jʿal lī ʿinda qabri nabīyika (ṣallā -llāhu ʿalayhi waʾ-ālihi wa-sallama) qarāran wa-mustaqarrān

"O God! Make my heart to be righteous, and my livelihood to be constant, and my sustenance to be continuous, and Make for me, in the presence of Your Prophet (God bless him and his progeny and grant him peace) a dwelling and a rest."[21]

Form

The call to prayer is said after entering the time of prayer. The muezzin usually stands during the call to prayer.[23] It is common for the muezzin to put his hands to his ears when reciting the adhan. Each phrase is followed by a longer pause and is repeated one or more times according to fixed rules. During the first statement each phrase is limited in tonal range, less melismatic, and shorter. Upon repetition the phrase is longer, ornamented with melismas, and may possess a tonal range of over an octave. The adhan's form is characterised by contrast and contains twelve melodic passages which move from one to another tonal center of one maqam a fourth or fifth apart. Various geographic regions in the Middle East traditionally perform the adhan in particular maqamat: Medina, Saudi Arabia uses Maqam Bayati while Mecca uses Maqam Hijaz. The tempo is mostly slow; it may be faster and with fewer melismas for the sunset prayer. During festivals, it may be performed antiphonally as a duet.[24] Duration can be 4 minutes, but also longer, and then continuing with the shorter iqama.[25]

Modern legal status

Australia

There are controversies due to community-centric disagreements at mosques in Australia, such as ongoing parking disputes at Al Zahra in Arncliffe,[26] noise complaints at Gallipoli Mosque[27] and Lakemba Mosque[28] in Sydney, and public filming at Albanian Australian Islamic Society and the Keysborough Turkish Islamic and Cultural Centre[29] in Melbourne.[30]

Bangladesh

In 2016, opposition leader Khaleda Zia alleged the government was preventing the broadcasting of adhans through loudspeakers, with government officials citing security concerns for the prime minister Sheikh Hasina".[31]

Israel

In 2016, Israel's ministerial committee approved a draft bill that limits the volume of the use of public address systems for calls to prayer, particularly outdoor loudspeakers for the adhan, citing it as a factor of noise pollution, the draft bill was never enacted and has been in limbo ever since.[32][33][34] The bill was submitted by Knesset member Motti Yogev of the far right Zionist party Jewish Home and Robert Ilatov of the right wing Yisrael Beiteinu.[33] The ban is meant to affect three mosques in Abu Dis village of East Jerusalem, disbarring them from broadcasting the morning call (fajr) prayers.[35] The bill was backed by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu who said: "I cannot count the times — they are simply too numerous — that citizens have turned to me from all parts of Israeli society, from all religions, with complaints about the noise and suffering caused to them by the excessive noise coming to them from the public address systems of houses of prayer."[34] The Israel Democracy Institute, a non-partisan think tank, expressed concerns that it specifically stifles the rights of Muslims, and restricts their freedom of religion.[34][35]

Turkey

As an extension of the reforms brought about by the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, the Turkish government at the time, encouraged by Atatürk, introduced secularism to Turkey. The program involved implementing a Turkish adhan program as part of its goals, as opposed to the conventional Arabic call to prayer.[36] Following the conclusion of said debates, on the 1 February 1932, the adhan was chanted in Turkish and the practice was continued for a period of 18 years. There was some resistance against the adhan in the Turkish language and protests surged. In order to suppress these protests, in 1941, a new law was issued, under which people who chanted the adhan in Arabic could be imprisoned for up to 3 months and be fined up to 300 Turkish Lira.

On 17 June 1950, a new government led by Adnan Menderes, restored Arabic as the liturgical language.[37]

Sweden

The Fittja Mosque in Botkyrka, south of Stockholm, was in 2013 the first mosque to be granted permission for a weekly public call to Friday prayer, on condition that the sound volume does not exceed 60 dB.[38] In Karlskrona (province of Blekinge, southern Sweden) the Islamic association built a minaret in 2017 and has had weekly prayer calls since then.[39][40] The temporary mosque in Växjö filed for a similar permission in February 2018,[41] which sparked a nationwide debate about the practice.[42][43][44] A yearlong permission was granted by the Swedish Police Authority in May the same year.[45][46]

Kuwait and UAE

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Kuwait, some cities changed their adhan from the usual hayya 'ala as-salah, meaning "come to prayer", to as-salatu fi buyutikum meaning "pray in your homes" or ala sallu fi rihalikum meaning "pray where you are".[47]

Other Muslim countries (notably Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and Indonesia) also made this change because Muslims are prohibited to pray in mosques during the pandemic as preventive measures to stop the chain of the outbreak. The basis for the authority to change a phrase in the adhan was justified by Muhammad's instructions while calling for adhan during adverse conditions.[48]

Tajikistan

The usage of loudspeakers to broadcast the adhan was banned in 2009 with Law No. 489 of 26 March 2009 on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Unions.[49]

Uzbekistan

In 2005, former Uzbek president Islam Karimov banned the Muslim call to prayer from being broadcast in the country; the ban was lifted in November 2017 by his successor, Shavkat Mirziyoyev.[50]

In other countries, there is no written law forbidding the distribution of the call to prayer in mosques and prayer halls.

In popular culture

In television

In some Muslim-majority countries, television stations usually broadcasts the adhan at prayer times, in a similar fashion to radio stations. In Indonesia and Malaysia, it is mandatory for all television stations to broadcast the adhan at Fajr and Magrib prayers, with the exception of non-Muslim religious stations. Islamic religious stations often broadcast the adhan at all five prayer times.

The adhan are commonly broadcast with a visual cinematic sequence depicting mosques and worshippers attending to the prayer. Some television stations in both Malaysia and Indonesia often utilize a more artistic or cultural approach to the cinematic involving multiple actors and religious-related plotlines.[51]

The 1991-1994 recording of Masjid al-Haram muezzin, Sheikh Ali Ahmed Mulla is best known for its use in various television and radio stations.

Turkish National Anthem

The adhan is referenced in the eighth verse of İstiklâl Marşı, the Turkish national anthem:

The sole wish of my soul, oh glorious God, from You is that,

No heathen would ever, on the bosom of my temple, lay hand!

These adhans, whose testimonies are the ground of religion,

Should resound far and wide over my eternal homeland.

"The Armed Man"

The adhan appears in "The Armed Man: A Mass For Peace" composed by Karl Jenkins.

See also

- Barechu - Jewish call to prayer

- Church bells - Christian call to prayer

- Dhikr

- Tashahhud

References

- 1 2 3 "Adhane - Appel à la prière depuis la Mecque". YouTube.

- 1 2 3 Dessing, Nathal M. (2001). Rituals of Birth, Circumcision, Marriage, and Death Among Muslims in the Netherlands. Peeters Publishers. p. 25. ISBN 978-9-042-91059-1.

- ↑ "Orhan SELEN - EZAN MAKAMLARI".

- ↑ Miller, Roland E. (2015). Mappila Muslim Culture. State University of New York. p. 397.

- ↑ Gottheil, Richard J. H. (1910). "The Origin and History of the Minaret". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 30 (2): 132–154. doi:10.2307/3087601. JSTOR 3087601.

- ↑ Mohammad Taqi al-Modarresi (March 26, 2016). The Laws of Islam (PDF). Enlight Press. ISBN 978-0994240989. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2019. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ↑ Lee, Tong Soon (1999). "Technology and the Production of Islamic Space: The Call to Prayer in Singapore". Ethnomusicology. 43 (1): 86–100. doi:10.2307/852695. JSTOR 852695.

- ↑ Özdemir, Adil; Frank, Kenneth (2000), "The Call to Prayer", Visible Islam in Modern Turkey, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 106–114, doi:10.1057/9780230286894_9, ISBN 978-1-349-41721-6, retrieved October 12, 2022

- ↑ William Muir, The Life of Mohammad from Original Sources, reprinted by Adamant Media ISBN 1-4021-8272-4

- ↑ Ludwig W. Adamec (2009), Historical Dictionary of Islam, p.68. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810861615. Quote: "Bilal, ..., was the first mu'azzin."

- 1 2 "Sahih Muslim". sunnah.com. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- 1 2 Sunan al-Tirmidhi (Arabic) Chapter of Fitan, 2:45 (India) and 4:501 Tradition # 2225 (Egypt); Hadith #2149 (numbering of al-'Alamiyyah)

- ↑ Haykal, Muhammad Husayn (May 1994). The Life of Muhammad. p. 200. ISBN 9789839154177.

- ↑ Quran : Surah Sajda: Ayah 24-25

- ↑ Muwatta

- ↑ Sahih Al-Bukhari #548

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Sahih Al-Bukhari 3370

- ↑ "Dua after azan (adhan) | sunnah of Muhammad (SAW)".

- ↑ Abu Dawud 524

- 1 2 Al-Kulayni, Ya'qub (940). الكافي [Al-Kafi] (PDF) (in Arabic and English). Hub-e-Ali.

- ↑ Al-Kulayni, Ya'qub (940). الكافي [Al-Kafi] (PDF) (in Arabic and English). Hub-e-Ali.

- ↑ Mohammad Taqi al-Modarresi (26 March 2016). The Laws of Islam (PDF). Enlight Press. p. 470. ISBN 978-0994240989. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ↑ Touma, Habib Hassan (1996). The Music of the Arabs, p.157-158, trans. Laurie Schwartz. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-88-8.

- ↑ "Reciting the Adhan | Guide to the Islamic call to prayer [History, Meaning and Soundscapes]". August 2, 2022.

- ↑ "Inconsiderate Parking Al-Zahra Arncliffe Mosque".

- ↑ "First Azan - Muslim call to prayer in Sydney - Australia". YouTube.

- ↑ "Sydney's Lakemba mosque to broadcast Muslim call to prayer over loudspeakers".

- ↑ "Emotional Azan by Idris Aslami - Filmed at Mosque in Australia (2017)". YouTube.

- ↑ "First Adhan Called from Melbourne Mosque Minaret". YouTube.

- ↑ "Azan not being allowed thru loudhailers for Hasina's security: Khaleda". Prothom Alo. Prothom Alo. June 28, 2016. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ↑ "Israel to limit volume of prayer call from mosques".

- 1 2 "Israel to ban use of loudspeakers for 'Azaan' despite protest". The Financial Express. Ynet. November 14, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Israeli PM backs bill to limit Azan". Dawn. AFP. November 14, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- 1 2 Hawwash, Kamel (November 7, 2016). "Israel's ban on the Muslim call to prayer in Jerusalem is the tip of the iceberg". Middle East Monitor. Middle East Monitor. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ↑ The adhan in Turkey Archived April 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Aydar, Hidayet (2006). "The issue of chanting the adhan in languages other than Arabic and related social reactions against it in Turkey". dergipark.gov.tr. pp. 59–62. Archived from the original on January 12, 2019. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ↑ "Ljudkablar dras för första böneutropet" [Cables laid out for the first call to prayer] (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter. April 24, 2014.

- ↑ Nyheter, S. V. T. (October 13, 2017). "Blekinge har fått sin första minaret" [Blekinge has gotten its first minaret]. SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Sveriges Television. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ↑ "Swedish town allows calls to prayer from minaret". Anadolu Agency. November 17, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ↑ Nyheter, S. V. T. (February 12, 2018). "Moskén i Växjö vill ha böneutrop" [The mosque in Växjö wants prayer calls]. SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Sveriges Television. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ "Christian Democrat leader opposes Muslim call to prayer in Sweden". Sveriges Radio. Radio Sweden. March 15, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ Lawal Olatunde (February 14, 2018). "Swedish church supports Muslims Adhan". Islamic Hotspot. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ "This Jewish leader is defending the Muslim call to prayer in Sweden". The New Arab. March 19, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ↑ Thorneus, Ebba (May 8, 2018). "Polisen tillåter böneutrop via högtalare". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ↑ Broke, Cecilia (May 8, 2018). "Polisen ger klartecken till böneutrop i Växjö" [The Police gives clearance for prayer calls in Växjö]. SVT (in Swedish). Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ↑ Kuwait mosques tell believers to pray at home amid coronavirus pandemic alaraby.co.uk

- ↑ Bukhari: Volume 1, Book 11, Number 605

- ↑ Roznai, Yaniv (June 7, 2017). "Negotiating the Eternal: The Paradox of Entrenching Secularism in Constitutions". Michigan State Law Review. Rochester, NY. 253: 282. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2982275. SSRN 2982275.

- ↑ "An Uzbek spring has sprung, but summer is still a long way off". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ↑ "Adzan Maghrib RCTI 2015 (from YouTube)". YouTube. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

External links

- Adhan from the Grand Mosque (Masjid al Haram) recited by Sheikh Ali Ahmed Mulla

- Adhan from the Prophet's Mosque (Masjid Nabawi), Madinah al Munawarah

- Adhan (call for prayer) from a mosque

- Tweaking the Azaan and other measures Muslim countries have taken to combat the virus

- Meaning of the adhan Archived March 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Ezan video at Hagia Sophia