| Ashur-bel-nisheshu | |

|---|---|

| Issi'ak Assur | |

| King of Assur | |

| Reign | c. 1417–1409 BC[1] |

| Predecessor | Ashur-nirari II |

| Successor | Ashur-rim-nisheshu |

| Issue | Ashur-rim-nisheshu, Eriba-Adad I |

| Father | Ashur-nirari II |

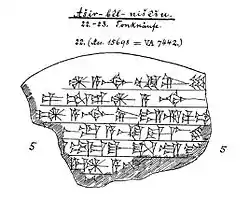

Aššūr-bēl-nīšēšu, inscribed 𒁹𒀭𒀸𒋩𒂗𒌦𒈨𒌍𒋙 mdaš-šur-EN-UN.MEŠ--šú,[i 1][i 2][i 3] and meaning “(the god) Aššur (is) lord of his people,”[2] was the ruler of Assyria c. 1417–1409 BC or 1407–1398 BC (short chronology), the variants due to uncertainties in the later chronology. He succeeded his father, Aššur-nērārī II, to the throne and is best known for his treaty with Kassite king Karaindaš.

Biography

As was the practice during this period of the Assyrian monarchy, he modestly titled himself “vice-regent”, or išši'ak Aššur, of the god Ashur.[3] The Synchronistic Chronicle[i 5] records his apparently amicable territorial treaty with Karaindaš, king of Babylon, and recounts that they “took an oath together concerning this very boundary.”[4]: 158 His numerous clay cone inscriptions (line art for an example pictured) celebrate his re-facing of Puzur-Aššur III’s wall of the “New City” district of Assur.[3]

Contemporary legal documents detail sales of land, houses, and slaves and payment in lead. The Assyrian credit system was fairly sophisticated, with loans issued for commodities such as barley and lead, interest coming due when repayment way delayed. The security posted for loans could include property, the person of the debtor or indeed his children.[5]

There is a discrepancy in the data about his son and eventual successor. The Assyrian King List gives his immediate successor, Aššur-rā’im-nišēšu, as his son, but Aššur-rā’im-nišēšu's own contemporary inscription[i 6] names his father as Aššur-nērārī II, suggesting that he may have been a brother of Aššūr-bēl-nīšēšu. The confusion is further compounded with the Khorsabad Kinglist[i 2] and the SDAS Kinglist[i 3] identifying Eriba-Adad I, who ascended the throne eighteen years later, as his son[4]: 209 while the Nassouhi copy[i 1] identifies him as the son of Aššur-rā’im-nišēšu.[6]

Inscriptions

- 1 2 Nassouhi King List, Istanbul A. 116 (Assur 8836), iii 11–12.

- 1 2 Khorsabad King List, IM 60017 (excavation nos.: DS 828, DS 32-54), iii 5–6.

- 1 2 SDAS King List, tablet IM 60484, ii 38.

- ↑ Cone VAT 7442, first published KAH 2 no. 22 (1922).

- ↑ Synchronistic Chronicle (ABC 21), tablet K4401a, i 1–4.

- ↑ Cone VAT? 2764, first published KAH 1 no. 63 (1911).

References

- ↑ Chen, Fei (2020). "Appendix I: A List of Assyrian Kings". Study on the Synchronistic King List from Ashur. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-9004430914.

- ↑ K. Åkerman (1998). K. Radner (ed.). The Prosopography of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Volume 1, Part I: A. The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. p. 171.

- 1 2 A. K. Grayson (1972). Assyrian Royal Inscriptions, Volume 1. Otto Harrassowitz. p. 38. §236—240.

- 1 2 A. K. Grayson (1975). Assyrian and Babylonian chronicles. J. J. Augustin. pp. 158, 209.

- ↑ C. J. Gadd (1975). "XVIII: Assyria and Babylon, 1370—1300 B.C.". In I. E. S. Edwards; C. J. Gadd; N. G. L. Hammond; S. Solberger (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume II, Part 2, History of the Middle East and the Aegean Region, 1380 – 1000 BC. Cambridge University Press. pp. 38–39.

- ↑ J. A. Brinkman (1973). "Comments on the Nasouhi Kinglist and the Assyrian Kinglist Tradition". Orientalia. 42: 312.