יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז (Yehudei Ashkenaz)

אשכנזישע יידן (Ashkhnzishe eydn) | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 10[1]–11.2[2] million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States | 5–6 million[3] |

| Israel | 2.8 million[1][4] |

| Russia | 194,000–500,000; according to the FJCR, up to 1 million of Jewish descent |

| Argentina | 300,000 |

| United Kingdom | 260,000 |

| Canada | 240,000 |

| France | 200,000 |

| Germany | 200,000 |

| Ukraine | 150,000 |

| Australia | 120,000 |

| South Africa | 80,000 |

| Belarus | 80,000 |

| Brazil | 80,000 |

| Hungary | 75,000 |

| Chile | 70,000 |

| Belgium | 30,000 |

| Netherlands | 30,000 |

| Moldova | 30,000 |

| Italy | 28,000 |

| Poland | 25,000 |

| Mexico | 18,500 |

| Sweden | 18,000 |

| Latvia | 10,000 |

| Romania | 10,000 |

| Austria | 9,000 |

| Turkey | 7,000 |

| New Zealand | 5,000 |

| Colombia | 4,900 |

| Azerbaijan | 4,300 |

| Lithuania | 4,000 |

| Czech Republic | 3,000 |

| Slovakia | 3,000 |

| Ireland | 2,500 |

| Estonia | 1,000 |

| Languages | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Majority Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Sephardi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, other Jewish ethnic divisions and Samaritans;[6][7][8] Germans and other Germanic peoples;[9] Russians, Poles, and other Slavic peoples;[9][10] Assyrians,[6][7] Arabs,[6][7][11][12] Mediterranean groups (Italians,[13][14] Spaniards)[15][16][17][18][19] | |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

Ashkenazi Jews (/ˌɑːʃkəˈnɑːzi, ˌæʃ-/ A(H)SH-kə-NAH-zee;[20] Hebrew: יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, romanized: Yehudei Ashkenaz, lit. 'Jews of Germania'; Yiddish: אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, romanized: Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim[lower-alpha 1], constitute a Jewish diaspora population that emerged in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium CE.[22] They traditionally spoke Yiddish[22] and largely migrated towards northern and eastern Europe during the late Middle Ages due to persecution.[23][24] Hebrew was primarily used as a literary and sacred language until its 20th-century revival as a common language in Israel.

Ashkenazim adapted their traditions to Europe and underwent a transformation in their interpretation of Judaism.[25] In the late 18th and 19th centuries, Jews who remained in or returned to historical German lands experienced a cultural reorientation. Under the influence of the Haskalah and the struggle for emancipation, as well as the intellectual and cultural ferment in urban centres, some gradually abandoned Yiddish in favor of German and developed new forms of Jewish religious life and cultural identity.[26]

Throughout the centuries, Ashkenazim made significant contributions to Europe's philosophy, scholarship, literature, art, music, and science.[27][28][29][30]

As a proportion of the world Jewish population, Ashkenazim were estimated to be 3% in the 11th century, rising to 92% in 1930 near the population's peak.[31] The Ashkenazi population was significantly diminished by the Holocaust carried out by Nazi Germany during World War II, affecting almost every European Jewish family.[32][33] In 1933, prior to World War II, the estimated worldwide Jewish population was 15.3 million.[34] Israeli demographer and statistician Sergio D. Pergola implied that Ashkenazim comprised 65%–70% of Jews worldwide in 2000,[35] while other estimates suggest more than 75%.[36] As of 2013, the population was estimated to be between 10 million[1] and 11.2 million.[2]

Genetic studies indicate that Ashkenazim have both Levantine and European (mainly southern European) ancestry. These studies draw diverging conclusions about the degree and sources of European admixture, with some focusing on the European genetic origin in Ashkenazi maternal lineages, contrasting with the predominantly Middle Eastern genetic origin in paternal lineages.[37][38][39][40][41]

Etymology

The name Ashkenazi derives from the biblical figure of Ashkenaz, the first son of Gomer, son of Japhet, son of Noah, and a Japhetic patriarch in the Table of Nations (Genesis 10). The name of Gomer has often been linked to the Cimmerians.

The Biblical Ashkenaz is usually derived from Assyrian Aškūza (cuneiform Aškuzai/Iškuzai), a people who expelled the Cimmerians from the Armenian area of the Upper Euphrates;[42] the name Aškūza is identified with the Scythians.[43][44] The intrusive n in the Biblical name is likely due to a scribal error confusing a vav ו with a nun נ.[44][45][46]

In Jeremiah 51:27, Ashkenaz figures as one of three kingdoms in the far north, the others being Minni and Ararat (corresponding to Urartu), called on by God to resist Babylon.[46][47] In the Yoma tractate of the Babylonian Talmud the name Gomer is rendered as Germania, which elsewhere in rabbinical literature was identified with Germanikia in northwestern Syria, but later became associated with Germania. Ashkenaz is linked to Scandza/Scanzia, viewed as the cradle of Germanic tribes, as early as a 6th-century gloss to the Historia Ecclesiastica of Eusebius.[48]

In the 10th-century History of Armenia of Yovhannes Drasxanakertc'i (1.15), Ashkenaz was associated with Armenia,[49] as it was occasionally in Jewish usage, where its denotation extended at times to Adiabene, Khazaria, Crimea and areas to the east.[50] His contemporary Saadia Gaon identified Ashkenaz with the Saquliba or Slavic territories,[51] and such usage covered also the lands of tribes neighboring the Slavs, and Eastern and Central Europe.[50] In modern times, Samuel Krauss identified the Biblical "Ashkenaz" with Khazaria.[52]

Sometime in the Early Medieval period, the Jews of central and eastern Europe came to be called by this term.[46] Conforming to the custom of designating areas of Jewish settlement with biblical names, Spain was denominated Sefarad (Obadiah 20), France was called Tsarefat (1 Kings 17:9), and Bohemia was called the Land of Canaan.[53] By the high medieval period, Talmudic commentators like Rashi began to use Ashkenaz/Eretz Ashkenaz to designate Germany, earlier known as Loter,[46][48] where, especially in the Rhineland communities of Speyer, Worms and Mainz, the most important Jewish communities arose.[54] Rashi uses leshon Ashkenaz (Ashkenazi language) to describe Yiddish, and Byzantium and Syrian Jewish letters referred to the Crusaders as Ashkenazim.[48] Given the close links between the Jewish communities of France and Germany following the Carolingian unification, the term Ashkenazi came to refer to the Jews of both medieval Germany and France.[55]

History

Like other Jewish ethnic groups, the Ashkenazi originate from the Israelites[56][57][58] and Hebrews[59][60] of historical Israel and Judah. Ashkenazi Jews share a significant amount of ancestry with other Jewish populations and derive their ancestry mostly from populations in the Middle East, Southern Europe and Eastern Europe.[10] Other than their origins in ancient Israel, the question of how Ashkenazi Jews came to exist as a distinct community is unknown, and has given rise to several theories.[61][62]

Early Jewish communities in Europe

Beginning in the fourth century BCE, Jewish colonies sprang up in southern Europe, including the Aegean Islands, Greece, and Italy. Jews left ancient Israel for a number of causes, including a number of push and pull factors. More Jews moved into these communities as a result of wars, persecution, unrest, and for opportunities in trade and commerce.

Jews migrated to southern Europe from the Middle East voluntarily for opportunities in trade and commerce. Following Alexander the Great's conquests, Jews migrated to Greek settlements in the Eastern Mediterranean, spurred on by economic opportunities. Jewish economic migration to southern Europe is also believed to have occurred during the Roman period.

In 63 BCE, the Siege of Jerusalem saw the Roman Republic conquer Judea, and thousands of Jewish prisoners of war were brought to Rome as slaves. After gaining their freedom, they settled permanently in Rome as traders.[63] It is likely that there was an additional influx of Jewish slaves taken to southern Europe by Roman forces after the capture of Jerusalem by the forces of Herod the Great with assistance from Roman forces in 37 BCE. It is known that Jewish war captives were sold into slavery after the suppression of a minor Jewish revolt in 53 BCE, and some were probably taken to southern Europe.[64]

Regarding Jewish settlements founded in southern Europe during the Roman era, E. Mary Smallwood wrote that "no date or origin can be assigned to the numerous settlements eventually known in the west, and some may have been founded as a result of the dispersal of Palestinian Jews after the revolts of AD 66–70 and 132–135, but it is reasonable to conjecture that many, such as the settlement in Puteoli attested in 4 BC, went back to the late republic or early empire and originated in voluntary emigration and the lure of trade and commerce."[65][66][67]

Jewish-Roman Wars

The first and second centuries CE saw a series of unsuccessful large-scale Jewish revolts against Rome. The Roman suppression of these revolts led to wide-scale destruction, a very high toll of life and enslavement. The First Jewish-Roman War (66–73 CE) resulted in the destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple. Two generations later, the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–136 CE) erupted. Judea's countryside was devastated, and many were killed, displaced or sold into slavery.[68][69][70][71] Jerusalem was rebuilt as a Roman colony under the name of Aelia Capitolina, and the province of Judea was renamed Syria Palaestina.[72][73] Jews were prohibited from entering the city on pain of death. Jewish presence in the region significantly dwindled after the failure of the Bar Kokhba revolt.[74]

With their national aspirations crushed and widespread devastation in Judea, despondent Jews migrated out of Judea in the aftermath of both revolts, and many settled in southern Europe. In contrast to the earlier Assyrian and Babylonian captivities, the movement was by no means a singular, centralized event, and a Jewish diaspora had already been established before.

During both of these rebellions, many Jews were captured and sold into slavery by the Romans. According to the Jewish historian Josephus, 97,000 Jews were sold as slaves in the aftermath of the first revolt.[75] In one occasion, Vespasian reportedly ordered 6,000 Jewish prisoners of war from Galilee to work on the Isthmus of Corinth in Greece.[76] Jewish slaves and their children eventually gained their freedom and joined local free Jewish communities.[77]

Late antiquity

Many Jews were denied full Roman citizenship until Emperor Caracalla granted all free peoples this privilege in 212 CE. Jews were required to pay a poll tax until the reign of Emperor Julian in 363 CE. In the late Roman Empire, Jews were free to form networks of cultural and religious ties and enter into various local occupations. However, after Christianity became the official religion of Rome and Constantinople in 380 CE, Jews were increasingly marginalized.

The Synagogue in the Agora of Athens is dated to the period between 267 and 396 CE. The Stobi Synagogue in Macedonia was built on the ruins of a more ancient synagogue in the 4th century, while later in the 5th century, the synagogue was transformed into a Christian basilica.[78] Hellenistic Judaism thrived in Antioch and Alexandria, and many of these Greek-speaking Jews would convert to Christianity.[79]

Sporadic[80] epigraphic evidence in gravesite excavations, particularly in Brigetio (Szőny), Aquincum (Óbuda), Intercisa (Dunaújváros), Triccinae (Sárvár), Savaria (Szombathely), Sopianae (Pécs) in Hungary, and Mursa (Osijek) in Croatia, attest to the presence of Jews after the 2nd and 3rd centuries where Roman garrisons were established.[81] There was a sufficient number of Jews in Pannonia to form communities and build a synagogue. Jewish troops were among the Syrian soldiers transferred there, and replenished from the Middle East. After 175 CE Jews and especially Syrians came from Antioch, Tarsus, and Cappadocia. Others came from Italy and the Hellenized parts of the Roman Empire. The excavations suggest they first lived in isolated enclaves attached to Roman legion camps and intermarried with other similar oriental families within the military orders of the region.[80]

Raphael Patai states that later Roman writers remarked that they differed little in either customs, manner of writing, or names from the people among whom they dwelt; and it was especially difficult to differentiate Jews from the Syrians.[82][43] After Pannonia was ceded to the Huns in 433, the garrison populations were withdrawn to Italy, and only a few, enigmatic traces remain of a possible Jewish presence in the area some centuries later.[83] No evidence has yet been found of a Jewish presence in antiquity in Germany beyond its Roman border, nor in Eastern Europe. In Gaul and Germany itself, with the possible exception of Trier and Cologne, the archeological evidence suggests at most a fleeting presence of very few Jews, primarily itinerant traders or artisans.[84]

Estimating the number of Jews in antiquity is a task fraught with peril due to the nature of and lack of accurate documentation. The number of Jews in the Roman Empire for a long time was based on the accounts of Syrian Orthodox bishop Bar Hebraeus who lived between 1226 and 1286 CE, who stated by the time of the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, as many as six million Jews were already living in the Roman Empire, a conclusion which has been contested as highly exaggerated. The 13th-century author Bar Hebraeus gave a figure of 6,944,000 Jews in the Roman world. Salo Wittmayer Baron considered the figure convincing.[85] The figure of seven million within and one million outside the Roman world in the mid-first century became widely accepted, including by Louis Feldman. However, contemporary scholars now accept that Bar Hebraeus based his figure on a census of total Roman citizens and thus included non-Jews, the figure of 6,944,000 being recorded in Eusebius' Chronicon.[86]: 90, 94, 104–105 [87] Louis Feldman, previously an active supporter of the figure, now states that he and Baron were mistaken.[88]: 185 Philo gives a figure of one million Jews living in Egypt. Brian McGing rejects Baron's figures entirely, arguing that we have no clue as to the size of the Jewish demographic in the ancient world.[86]: 97–103 Sometimes the scholars who accepted the high number of Jews in Rome had explained it by Jews having been active in proselytising.[89] The idea of ancient Jews trying to convert Gentiles to Judaism is nowadays rejected by several scholars.[90] The Romans did not distinguish between Jews inside and outside of the land of Israel/Judaea. They collected an annual temple tax from Jews both in and outside of Israel. The revolts in and suppression of diaspora communities in Egypt, Libya and Crete during the Kitos War of 115–117 CE had a severe impact on the Jewish diaspora.

A substantial Jewish population emerged in northern Gaul by the Middle Ages,[91] but Jewish communities existed in 465 CE in Brittany, in 524 CE in Valence, and in 533 CE in Orléans.[92] Throughout this period and into the early Middle Ages, some Jews assimilated into the dominant Greek and Latin cultures, mostly through conversion to Christianity.[93] King Dagobert I of the Franks expelled the Jews from his Merovingian kingdom in 629. Jews in former Roman territories faced new challenges as harsher anti-Jewish Church rulings were enforced.

Early Middle Ages

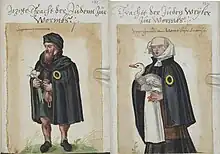

Charlemagne's expansion of the Frankish empire around 800, including northern Italy and Rome, brought on a brief period of stability and unity in Francia. This created opportunities for Jewish merchants to settle again north of the Alps. Charlemagne granted the Jews freedoms similar to those once enjoyed under the Roman Empire. In addition, Jews from southern Italy, fleeing religious persecution, began to move into Central Europe. Returning to Frankish lands, many Jewish merchants took up occupations in finance and commerce, including money lending, or usury. (Church legislation banned Christians from lending money in exchange for interest.) From Charlemagne's time to the present, Jewish life in northern Europe is well documented. By the 11th century, when Rashi of Troyes wrote his commentaries, Jews in what came to be known as "Ashkenaz" were known for their halakhic learning, and Talmudic studies. They were criticized by Sephardim and other Jewish scholars in Islamic lands for their lack of expertise in Jewish jurisprudence and general ignorance of Hebrew linguistics and literature.[94] Yiddish emerged as a result of Judeo-Latin language contact with various High German vernaculars in the medieval period.[95] It is a Germanic language written in Hebrew letters, and heavily influenced by Hebrew and Aramaic, with some elements of Romance and later Slavic languages.[96]

High and Late Middle Ages migrations

Historical records show evidence of Jewish communities north of the Alps and Pyrenees as early as the 8th and 9th centuries. By the 11th century, Jewish settlers moving from southern European and Middle Eastern centers (such as Babylonian Jews[97] and Persian Jews[98]) and Maghrebi Jewish traders from North Africa who had contacts with their Ashkenazi brethren and had visited each other from time to time in each's domain[99] appear to have begun to settle in the north, especially along the Rhine, often in response to new economic opportunities and at the invitation of local Christian rulers. Thus Baldwin V, Count of Flanders, invited Jacob ben Yekutiel and his fellow Jews to settle in his lands; and soon after the Norman conquest of England, William the Conqueror likewise extended a welcome to continental Jews to take up residence there. Bishop Rüdiger Huzmann called on the Jews of Mainz to relocate to Speyer. In all of these decisions, the idea that Jews had the know-how and capacity to jump-start the economy, improve revenues, and enlarge trade seems to have played a prominent role.[100] Typically, Jews relocated close to the markets and churches in town centres, where, though they came under the authority of both royal and ecclesiastical powers, they were accorded administrative autonomy.[100]

In the 11th century, both Rabbinic Judaism and the culture of the Babylonian Talmud that underlies it became established in southern Italy and then spread north to Ashkenaz.[101]

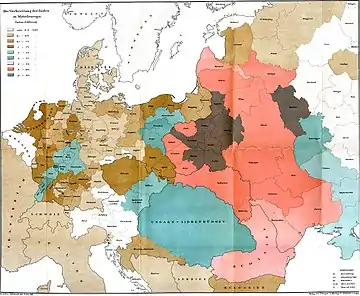

Numerous massacres of Jews occurred throughout Europe during the Christian Crusades. Inspired by the preaching of a First Crusade, crusader mobs in France and Germany perpetrated the Rhineland massacres of 1096, devastating Jewish communities along the Rhine River, including the SHuM cities of Speyer, Worms, and Mainz. The cluster of cities contain the earliest Jewish settlements north of the Alps, and played a major role in the formation of Ashkenazi Jewish religious tradition,[25] along with Troyes and Sens in France. Nonetheless, Jewish life in Germany persisted, while some Ashkenazi Jews joined Sephardic Jewry in Spain.[102] Expulsions from England (1290), France (1394), and parts of Germany (15th century), gradually pushed Ashkenazi Jewry eastward, to Poland (10th century), Lithuania (10th century), and Russia (12th century). Over this period of several hundred years, some have suggested, Jewish economic activity was focused on trade, business management, and financial services, due to several presumed factors: Christian European prohibitions restricting certain activities by Jews, preventing certain financial activities (such as "usurious" loans)[103] between Christians, high rates of literacy, near-universal male education, and ability of merchants to rely upon and trust family members living in different regions and countries.

In Poland, Jews were granted special protection by the Statute of Kalisz of 1264. By the 15th century, the Ashkenazi Jewish communities in Poland were the largest Jewish communities of the Diaspora.[104] This area, which eventually fell under the domination of Russia, Austria, and Prussia (Germany) following the Partitions of Poland, and was later largely regained by reborn Poland in the interbellum, would remain the main center of Ashkenazi Jewry until the Holocaust.

The answer to why there was so little assimilation of Jews in central and eastern Europe for so long would seem to lie in part in the probability that the alien surroundings in central and eastern Europe were not conducive, though there was some assimilation. Furthermore, Jews lived almost exclusively in shtetls, maintained a strong system of education for males, heeded rabbinic leadership, and had a very different lifestyle to that of their neighbours; all of these tendencies increased with every outbreak of antisemitism.[105]

In parts of Eastern Europe, before the arrival of the Ashkenazi Jews from Central Europe, some non-Ashkenazi Jews were present who spoke Leshon Knaan and held various other Non-Ashkenazi traditions and customs.[106] In 1966, the historian Cecil Roth questioned the inclusion of all Yiddish speaking Jews as Ashkenazim in descent, suggesting that upon the arrival of Ashkenazi Jews from central Europe to Eastern Europe, from the Middle Ages to the 16th century, there were a substantial number of non-Ashkenazim Jews already there who later abandoned their original Eastern European Jewish culture in favor of the Ashkenazi one.[107] However, according to more recent research, mass migrations of Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews occurred to Eastern Europe, from Central Europe in the west, who due to high birth rates absorbed and largely replaced the preceding non-Ashkenazi Jewish groups of Eastern Europe (whose numbers the demographer Sergio Della Pergola considers to have been small).[108] Genetic evidence also indicates that Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jews largely descend from Ashkenazi Jews who migrated from central to eastern Europe and subsequently experienced high birthrates and genetic isolation.[109]

Some Jewish immigration from southern Europe to Eastern Europe continued into the early modern period. During the 16th century, as conditions for Italian Jews worsened, many Jews from Venice and the surrounding area migrated to Poland and Lithuania. During the 16th and 17th centuries, some Sephardi Jews and Romaniote Jews from throughout the Ottoman Empire migrated to Eastern Europe, as did Arabic-speaking Mizrahi Jews and Persian Jews.[110][111][112][113]

Medieval references

In the first half of the 11th century, Hai Gaon refers to questions that had been addressed to him from Ashkenaz, by which he undoubtedly means Germany. Rashi in the latter half of the 11th century refers to both the language of Ashkenaz[114] and the country of Ashkenaz.[115] During the 12th century, the word appears quite frequently. In the Mahzor Vitry, the kingdom of Ashkenaz is referred to chiefly in regard to the ritual of the synagogue there, but occasionally also with regard to certain other observances.[116]

In the literature of the 13th century, references to the land and the language of Ashkenaz often occur. Examples include Solomon ben Aderet's Responsa (vol. i., No. 395); the Responsa of Asher ben Jehiel (pp. 4, 6); his Halakot (Berakot i. 12, ed. Wilna, p. 10); the work of his son Jacob ben Asher, Tur Orach Chayim (chapter 59); the Responsa of Isaac ben Sheshet (numbers 193, 268, 270).

In the Midrash compilation, Genesis Rabbah, Rabbi Berechiah mentions Ashkenaz, Riphath, and Togarmah as German tribes or as German lands. It may correspond to a Greek word that may have existed in the Greek dialect of the Jews in Syria Palaestina, or the text is corrupted from "Germanica". This view of Berechiah is based on the Talmud (Yoma 10a; Jerusalem Talmud Megillah 71b), where Gomer, the father of Ashkenaz, is translated by Germamia, which evidently stands for Germany, and which was suggested by the similarity of the sound.

In later times, the word Ashkenaz is used to designate southern and western Germany, the ritual of which sections differs somewhat from that of eastern Germany and Poland. Thus the prayer-book of Isaiah Horowitz, and many others, give the piyyutim according to the Minhag of Ashkenaz and Poland.

According to 16th-century mystic Rabbi Elijah of Chelm, Ashkenazi Jews lived in Jerusalem during the 11th century. The story is told that a German-speaking Jew saved the life of a young German man surnamed Dolberger. So when the knights of the First Crusade came to siege Jerusalem, one of Dolberger's family members who was among them rescued Jews in Palestine and carried them back to Worms to repay the favor.[117] Further evidence of German communities in the holy city comes in the form of halakhic questions sent from Germany to Jerusalem during the second half of the 11th century.[118]

Modern history

Material relating to the history of German Jews has been preserved in the communal accounts of certain communities on the Rhine, a Memorbuch, and a Liebesbrief, documents that are now part of the Sassoon Collection.[119] Heinrich Graetz also added to the history of German Jewry in modern times in the abstract of his seminal work, History of the Jews, which he entitled "Volksthümliche Geschichte der Juden."

In an essay on Sephardi Jewry, Daniel Elazar at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs[120] summarized the demographic history of Ashkenazi Jews in the last thousand years. He noted that at the end of the 11th century, 97% of world Jewry was Sephardic and 3% Ashkenazi; in the mid-17th century, "Sephardim still outnumbered Ashkenazim three to two"; by the end of the 18th century, "Ashkenazim outnumbered Sephardim three to two, the result of improved living conditions in Christian Europe versus the Ottoman Muslim world."[120] By 1930, Arthur Ruppin estimated that Ashkenazi Jews accounted for nearly 92% of world Jewry.[31] These factors are sheer demography showing the migration patterns of Jews from Southern and Western Europe to Central and Eastern Europe.

In 1740, a family from Lithuania became the first Ashkenazi Jews to settle in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem.[121]

In the generations after emigration from the west, Jewish communities in places like Poland, Russia, and Belarus enjoyed a comparatively stable socio-political environment. A thriving publishing industry and the printing of hundreds of biblical commentaries precipitated the development of the Hasidic movement as well as major Jewish academic centers.[122] After two centuries of comparative tolerance in the new nations, massive westward emigration occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries in response to pogroms in the east and the economic opportunities offered in other parts of the world. Ashkenazi Jews have made up the majority of the American Jewish community since 1750.[104]

In the context of the European Enlightenment, Jewish emancipation began in 18th century France and spread throughout Western and Central Europe. Disabilities that had limited the rights of Jews since the Middle Ages were abolished, including the requirements to wear distinctive clothing, pay special taxes, and live in ghettos isolated from non-Jewish communities and the prohibitions on certain professions. Laws were passed to integrate Jews into their host countries, forcing Ashkenazi Jews to adopt family names (they had formerly used patronymics). Newfound inclusion into public life led to cultural growth in the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment, with its goal of integrating modern European values into Jewish life.[123] As a reaction to increasing antisemitism and assimilation following the emancipation, Zionism developed in central Europe.[124] Other Jews, particularly those in the Pale of Settlement, turned to socialism. These tendencies would be united in Labor Zionism, the founding ideology of the State of Israel.

The Holocaust

Of the estimated 8.8 million Jews living in Europe at the beginning of World War II, the majority of whom were Ashkenazi, about 6 million – more than two-thirds – were systematically murdered in the Holocaust. These included 3 million of 3.3 million Polish Jews (91%); 900,000 of 1.5 million in Ukraine (60%); and 50–90% of the Jews of other Slavic nations, Germany, Hungary, and the Baltic states, and over 25% of the Jews in France. Sephardi communities suffered similar devastation in a few countries, including Greece, the Netherlands and the former Yugoslavia.[125] As the large majority of the victims were Ashkenazi Jews, their percentage dropped from an estimate of 92% of world Jewry in 1930[31] to nearly 80% of world Jewry today. The Holocaust also effectively put an end to the dynamic development of the Yiddish language in the previous decades, as the vast majority of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, around 5 million, were Yiddish speakers.[126] Many of the surviving Ashkenazi Jews emigrated to countries such as Israel, Canada, Argentina, Australia, and the United States after the war.[127]

Following the Holocaust, some sources place Ashkenazim today as making up approximately 83%–85% of Jews worldwide,[128][129][130][131] while Sergio DellaPergola in a rough calculation of Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, implies that Ashkenazi make up a notably lower figure, less than 74%.[35] Other estimates place Ashkenazi Jews as making up about 75% of Jews worldwide.[36]

Israel

In Israel, the term Ashkenazi is now used in a manner unrelated to its original meaning, often applied to all Jews who settled in Europe and sometimes including those whose ethnic background is actually Sephardic. Jews of any non-Ashkenazi background, including Mizrahi, Yemenite, Kurdish and others who have no connection with the Iberian Peninsula, have similarly come to be lumped together as Sephardic. Jews of mixed background are increasingly common, partly because of intermarriage between Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi, and partly because many do not see such historic markers as relevant to their life experiences as Jews.[132]

Religious Ashkenazi Jews living in Israel are obliged to follow the authority of the chief Ashkenazi rabbi in halakhic matters. In this respect, a religiously Ashkenazi Jew is an Israeli who is more likely to support certain religious interests in Israel, including certain political parties. These political parties result from the fact that a portion of the Israeli electorate votes for Jewish religious parties; although the electoral map changes from one election to another, there are generally several small parties associated with the interests of religious Ashkenazi Jews. The role of religious parties, including small religious parties that play important roles as coalition members, results in turn from Israel's composition as a complex society in which competing social, economic, and religious interests stand for election to the Knesset, a unicameral legislature with 120 seats.[133]

Ashkenazi Jews have played a prominent role in the economy, media, and politics[134] of Israel since its founding. During the first decades of Israel as a state, strong cultural conflict occurred between Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews (mainly east European Ashkenazim). The roots of this conflict, which still exists to a much smaller extent in present-day Israeli society, are chiefly attributed to the concept of the "melting pot".[135] That is to say, all Jewish immigrants who arrived in Israel were strongly encouraged to "meltdown" their own particular exilic identities[136] within the general social "pot" in order to become Israeli.[137]

United States of America

As of 2020, 63% of American Jews are Ashkenazim. A disproportionate amount of Ashkenazi Americans are religious compared to American Jews of other racial groups.[138] They live in large populations in the states of New York, California, Florida, and New Jersey.[139][140] The majority of American Ashkenazi Jewish voters vote for the Democratic Party, although Orthodox ones tend to support the Republican Party, while Conservative, Reform, and non denominational ones tend to support the Democratic Party.[141]

Definition

By religion

Religious Jews have minhagim, customs, in addition to halakha, or religious law, and different interpretations of the law. Different groups of religious Jews in different geographic areas historically adopted different customs and interpretations. On certain issues, Orthodox Jews are required to follow the customs of their ancestors and do not believe they have the option of picking and choosing. For this reason, observant Jews at times find it important for religious reasons to ascertain who their household's religious ancestors are in order to know what customs their household should follow. These times include, for example, when two Jews of different ethnic background marry, when a non-Jew converts to Judaism and determines what customs to follow for the first time, or when a lapsed or less observant Jew returns to traditional Judaism and must determine what was done in his or her family's past. In this sense, "Ashkenazic" refers both to a family ancestry and to a body of customs binding on Jews of that ancestry. Reform Judaism, which does not necessarily follow those minhagim, did nonetheless originate among Ashkenazi Jews.[142]

In a religious sense, an Ashkenazi Jew is any Jew whose family tradition and ritual follow Ashkenazi practice. Until the Ashkenazi community first began to develop in the Early Middle Ages, the centers of Jewish religious authority were in the Islamic world, at Baghdad and in Islamic Spain. Ashkenaz (Germany) was so distant geographically that it developed a minhag of its own. Ashkenazi Hebrew came to be pronounced in ways distinct from other forms of Hebrew.[143]

In this respect, the counterpart of Ashkenazi is Sephardic, since most non-Ashkenazi Orthodox Jews follow Sephardic rabbinical authorities, whether or not they are ethnically Sephardic. By tradition, a Sephardic or Mizrahi woman who marries into an Orthodox or Haredi Ashkenazi Jewish family raises her children to be Ashkenazi Jews; conversely an Ashkenazi woman who marries a Sephardi or Mizrahi man is expected to take on Sephardic practice and the children inherit a Sephardic identity, though in practice many families compromise. A convert generally follows the practice of the beth din that converted him or her. With the integration of Jews from around the world in Israel, North America, and other places, the religious definition of an Ashkenazi Jew is blurring, especially outside Orthodox Judaism.[144]

New developments in Judaism often transcend differences in religious practice between Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews. In North American cities, social trends such as the chavurah movement, and the emergence of "post-denominational Judaism"[145][146] often bring together younger Jews of diverse ethnic backgrounds. In recent years, there has been increased interest in Kabbalah, which many Ashkenazi Jews study outside of the Yeshiva framework. Another trend is the new popularity of ecstatic worship in the Jewish Renewal movement and the Carlebach style minyan, both of which are nominally of Ashkenazi origin.[147] Outside of Haredi communities, the traditional Ashkenazi pronunciation of Hebrew has also drastically declined in favor of the Sephardi-based pronunciation of Modern Hebrew.

By culture

Culturally, an Ashkenazi Jew can be identified by the concept of Yiddishkeit, which means "Jewishness" in the Yiddish language.[148] Yiddishkeit is specifically the Jewishness of Ashkenazi Jews.[149] Before the Haskalah and the emancipation of Jews in Europe, this meant the study of Torah and Talmud for men, and a family and communal life governed by the observance of Jewish Law for men and women. From the Rhineland to Riga to Romania, most Jews prayed in liturgical Ashkenazi Hebrew, and spoke Yiddish in their secular lives. But with modernization, Yiddishkeit now encompasses not just Orthodoxy and Hasidism, but a broad range of movements, ideologies, practices, and traditions in which Ashkenazi Jews have participated and somehow retained a sense of Jewishness. Although a far smaller number of Jews still speak Yiddish, Yiddishkeit can be identified in manners of speech, in styles of humor, in patterns of association. Broadly speaking, a Jew is one who associates culturally with Jews, supports Jewish institutions, reads Jewish books and periodicals, attends Jewish movies and theater, travels to Israel, visits historical synagogues, and so forth. It is a definition that applies to Jewish culture in general, and to Ashkenazi Yiddishkeit in particular.

As Ashkenazi Jews moved away from Europe, mostly in the form of aliyah to Israel, or immigration to North America, and other English-speaking areas such as South Africa; and Europe (particularly France) and Latin America, the geographic isolation that gave rise to Ashkenazim have given way to mixing with other cultures, and with non-Ashkenazi Jews who, similarly, are no longer isolated in distinct geographic locales. Hebrew has replaced Yiddish as the primary Jewish language for many Ashkenazi Jews, although many Hasidic and Hareidi groups continue to use Yiddish in daily life. (There are numerous Ashkenazi Jewish anglophones and Russian-speakers as well, although English and Russian are not originally Jewish languages.)

France's blended Jewish community is typical of the cultural recombination that is going on among Jews throughout the world. Although France expelled its original Jewish population in the Middle Ages, by the time of the French Revolution, there were two distinct Jewish populations. One consisted of Sephardic Jews, originally refugees from the Inquisition and concentrated in the southwest, while the other community was Ashkenazi, concentrated in formerly German Alsace, and mainly speaking a German dialect similar to Yiddish. (The third community of Provençal Jews living in Comtat Venaissin were technically outside France, and were later absorbed into the Sephardim.) The two communities were so separate and different that the National Assembly emancipated them separately in 1790 and 1791.[150]

But after emancipation, a sense of a unified French Jewry emerged, especially when France was wracked by the Dreyfus affair in the 1890s. In the 1920s and 1930s, Ashkenazi Jews from Europe arrived in large numbers as refugees from antisemitism, the Russian revolution, and the economic turmoil of the Great Depression. By the 1930s, Paris had a vibrant Yiddish culture, and many Jews were involved in diverse political movements. After the Vichy years and the Holocaust, the French Jewish population was augmented once again, first by Ashkenazi refugees from Central Europe, and later by Sephardi immigrants and refugees from North Africa, many of them francophone.

Ashkenazi Jews did not record their traditions or achievements by text, instead these traditions were passed down orally from one generation to the next.[151] The desire to maintain pre-Holocaust traditions relating to Ashkenazi culture has often been met with criticism by Jews in Eastern Europe.[151] Reasoning for this could be related to the development of a new style of Jewish arts and culture developed by the Jews of Palestine during the 1930s and 1940s, which in conjunction with the decimation of European Ashkenazi Jews and their culture by the Nazi regime made it easier to assimilate to the new style of ritual rather than try to repair the older traditions.[152] This new style of tradition was referred to as the Mediterranean Style, and was noted for its simplicity and metaphorical rejuvenation of Jews abroad.[152] This was intended to replace the Galut traditions, which were more sorrowful in practice.[152]

Then, in the 1990s, yet another Ashkenazi Jewish wave began to arrive from countries of the former Soviet Union and Central Europe. The result is a pluralistic Jewish community that still has some distinct elements of both Ashkenazi and Sephardic culture. But in France, it is becoming much more difficult to sort out the two, and a distinctly French Jewishness has emerged.[153]

By ethnicity

In an ethnic sense, an Ashkenazi Jew is one whose ancestry can be traced to the Jews who settled in Central Europe. For roughly a thousand years, the Ashkenazim were a reproductively isolated population in Europe, despite living in many countries, with little inflow or outflow from migration, conversion, or intermarriage with other groups, including other Jews. Human geneticists have argued that genetic variations have been identified that show high frequencies among Ashkenazi Jews, but not in the general European population, be they for patrilineal markers (Y-chromosome haplotypes) and for matrilineal markers (mitotypes).[154] Since the middle of the 20th century, many Ashkenazi Jews have intermarried, both with members of other Jewish communities and non-Jews.[155]

Customs, laws and traditions

The Halakhic practices of (Orthodox) Ashkenazi Jews may differ from those of Sephardi Jews, particularly in matters of custom. Differences are noted in the Shulkhan Arukh itself, in the gloss of Moses Isserles. Well known differences in practice include:

- Observance of Pesach (Passover): Ashkenazi Jews traditionally refrain from eating legumes, grain, millet, and rice (quinoa, however, has become accepted as foodgrain in the North American communities), whereas Sephardi Jews typically do not prohibit these foods.

- Ashkenazi Jews freely mix and eat fish and milk products; some Sephardic Jews refrain from doing so.

- Ashkenazim are more permissive toward the usage of wigs as a hair covering for married and widowed women.

- In the case of kashrut for meat, conversely, Sephardi Jews have stricter requirements – this level is commonly referred to as Beth Yosef. Meat products that are acceptable to Ashkenazi Jews as kosher may therefore be rejected by Sephardi Jews. Notwithstanding stricter requirements for the actual slaughter, Sephardi Jews permit the rear portions of an animal after proper Halakhic removal of the sciatic nerve, while many Ashkenazi Jews do not. This is not because of different interpretations of the law; rather, slaughterhouses could not find adequate skills for correct removal of the sciatic nerve and found it more economical to separate the hindquarters and sell them as non-kosher meat.

- Ashkenazi Jews often name newborn children after deceased family members, but not after living relatives. Sephardi Jews, in contrast, often name their children after the children's grandparents, even if those grandparents are still living. A notable exception to this generally reliable rule is among Dutch Jews, where Ashkenazim for centuries used the naming conventions otherwise attributed exclusively to Sephardim such as Chuts.

- Ashkenazi tefillin bear some differences from Sephardic tefillin. In the traditional Ashkenazic rite, the tefillin are wound towards the body, not away from it. Ashkenazim traditionally don tefillin while standing, whereas other Jews generally do so while sitting down.

- Ashkenazic traditional pronunciations of Hebrew differ from those of other groups. The most prominent consonantal difference from Sephardic and Mizrahic Hebrew dialects is the pronunciation of the Hebrew letter tav in certain Hebrew words (historically, in postvocalic undoubled context) as an /s/ and not a /t/ or /θ/ sound.

- The prayer shawl, or tallit (or tallis in Ashkenazi Hebrew), is worn by the majority of Ashkenazi men after marriage, but western European Ashkenazi men wear it from Bar Mitzvah. In Sephardi or Mizrahi Judaism, the prayer shawl is commonly worn from early childhood.[156]

Ashkenazic liturgy

The term Ashkenazi also refers to the nusach Ashkenaz (Hebrew, "liturgical tradition", or rite) used by Ashkenazi Jews in their Siddur (prayer book). A nusach is defined by a liturgical tradition's choice of prayers, the order of prayers, the text of prayers, and melodies used in the singing of prayers. Two other major forms of nusach among Ashkenazic Jews are Nusach Sefard (not to be confused with the Sephardic ritual), which is the general Polish Hasidic nusach, and Nusach Ari, as used by Lubavitch Hasidim.

Relations with Sephardim

Relations between Ashkenazim and Sephardim have at times been tense and clouded by arrogance, snobbery and claims of racial superiority with both sides claiming the inferiority of the other, based upon such features as physical traits and culture.[157][158][159][160][161]

North African Sephardim and Berber Jews were often looked down upon by Ashkenazim as second-class citizens during the first decade after the creation of Israel. This has led to protest movements such as the Israeli Black Panthers led by Saadia Marciano, a Moroccan Jew. Research in 2010 revealed a genetic common ancestry of all Jewish populations.[162] In some instances, Ashkenazi communities have accepted significant numbers of Sephardi newcomers, sometimes resulting in intermarriage and the possible merging between the two communities.[163]

Notable Ashkenazim

Ashkenazi Jews have a notable history of achievement in Western societies[164] in the fields of natural and social sciences, mathematics, literature, finance, politics, media, and others. In those societies where they have been free to enter any profession, they have a record of high occupational achievement, entering professions and fields of commerce where higher education is required.[165] Though Ashkenazi Jews have never exceeded 3% of the American population, Jews account for 37% of the winners of the U.S. National Medal of Science, 25% of the American Nobel Prize winners in literature, 40% of the American Nobel Prize winners in science and economics .[166]

Genetics

Genetic origins

Efforts to identify the origins of Ashkenazi Jews through DNA analysis began in the 1990s. There are three types of genetic origin testing, autosomal DNA (atDNA), mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and Y-chromosomal DNA (Y-DNA). Autosomal DNA is a mixture from an individual's entire ancestry. Y-DNA shows a male's lineage along his paternal line. mtDNA shows any person's lineage only along their maternal line. Genome-wide association studies have also been used for genetic origin testing.

Like most DNA studies of human migration patterns, the earliest studies on Ashkenazi Jews focused on the Y-DNA and mtDNA segments of the human genome. Both segments are unaffected by recombination (except for the ends of the Y chromosome – the pseudoautosomal regions known as PAR1 and PAR2), thus allowing tracing of direct maternal and paternal lineages.

These studies revealed that Ashkenazi Jews originate from an ancient (2000–700 BCE) population of the Middle East who spread to Europe.[167] Ashkenazic Jews display the homogeneity of a genetic bottleneck, meaning they descend from a larger population whose numbers were greatly reduced but recovered through a few founding individuals. Although the Jewish people, in general, were present across a wide geographical area as described, genetic research by Gil Atzmon of the Longevity Genes Project at Albert Einstein College of Medicine suggests "that Ashkenazim branched off from other Jews around the time of the destruction of the First Temple, 2,500 years ago ... flourished during the Roman Empire but then went through a 'severe bottleneck' as they dispersed, reducing a population of several million to just 400 families who left Northern Italy around the year 1000 for Central and eventually Eastern Europe."[168]

Various studies have drawn diverging conclusions about the degree and sources of the non-Levantine admixture in Ashkenazim,[37] particularly the extent of the non-Levantine origin in maternal lineages, which is in contrast to the predominant Levantine genetic origin in paternal lineages. But all studies agree that both lineages have genetic overlap with the Fertile Crescent, albeit at differing rates. Collectively, Ashkenazi Jews are less genetically diverse than other Jewish ethnic divisions, due to their genetic bottleneck.[169]

Male lineages: Y-chromosomal DNA

Most genetic studies of Ashkenazi Jews conclude that the male lines were from the Middle East.[170][171][172]

A 2000 study by Hammer et al.[173] found that the Y-chromosome of Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews contained mutations that are also common among Middle Eastern peoples, but uncommon among indigenous Europeans. This suggests that Ashkenazim male ancestors are mostly from the Middle East. Ashkenazi had less than 0.5% male genetic admixture per generation over an estimated 80 generations, with "relatively minor contribution of European Y chromosomes to the Ashkenazim," and the total admixture estimate "very similar to Motulsky's average estimate of 12.5%". This supported the finding that "Diaspora Jews from Europe, Northwest Africa, and the Near East resemble each other more closely than they resemble their non-Jewish neighbors." "Past research found that 50%–80% of DNA from the Ashkenazi Y chromosome, which is used to trace the male lineage, originated in the Near East," Richards said. The population has subsequently spread out.

A 2001 study by Nebel et al. showed that Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews share overall Near Eastern paternal ancestries. In comparison with data available from other relevant populations in the region, Jews were found to be more closely related to groups in the north of the Fertile Crescent. The study also found Eu 19 (R1a) chromosomes had elevated frequency among Ashkenazi Jews (13%), and they are very frequent in Central and Eastern Europeans (54–60%). They hypothesized that the differences among Ashkenazim could reflect low-level gene flow from surrounding European populations or genetic drift during isolation.[174] A 2005 study by Nebel et al., found a similar level of 11.5% of male Ashkenazim belonging to R1a1a (M17+), the dominant Y-chromosome haplogroup in Central and Eastern Europeans.[175] However, a 2017 study, of Ashkenazi Levites where the proportion reaches 50%, found a "rich variation of haplogroup R1a outside of Europe which is phylogenetically separate from the typically European R1a branches", and concludes that the particular R1a-Y2619 sub-clade is evidence for a local origin, and that this validates the "Middle Eastern origin of the Ashkenazi Levite lineage" which had previously been concluded based on a few samples.[176]

Female lineages: Mitochondrial DNA

Until recently, geneticists largely attributed the ethnogenesis of most of the world's Jewish populations, including Ashkenazim, to "women from each local population" whom the Jewish men "took as wives and converted to Judaism". Thus, in 2002, in line with this theory, David Goldstein reported that unlike Ashkenazi male lineages, female lineages "did not seem to be Middle Eastern", and that each community had its own genetic pattern and even that "in some cases the mitochondrial DNA was closely related to that of the host community." This suggested "that Jewish men had arrived from the Middle East, taken wives from the host population and converted them to Judaism, after which there was no further intermarriage with non-Jews."[154]

A 2006 study by Behar et al.,[38] of 1,000 units of haplogroup K (mtDNA), suggested that about 40% of today's Ashkenazim descend from just four women who were "likely from a Hebrew/Levantine mtDNA pool" originating in the Middle East in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. The rest of Ashkenazi mtDNA reportedly originated from about 150 women, most of whom were also likely of Middle Eastern origin.[38] Specifically, although haplogroup K is common throughout western Eurasia, its global distribution makes it very unlikely that "the four aforementioned founder lineages entered the Ashkenazi mtDNA pool via gene flow from a European host population".

A 2013 study of Ashkenazi mitochondrial DNA by a team led by Martin B. Richards agreed with the older hypothesis of the origin. It tested all 16,600 DNA units of mtDNA, and found that the four main female Ashkenazi founders had descent lines that were established in Europe 10,000 to 20,000 years in the past[177] while most of the remaining minor founders also have a deep European ancestry. The study argued that the great majority of Ashkenazi maternal lineages were not brought from the Near East or the Caucasus, but instead assimilated within Europe, primarily of Italian and Old French origins.[178] The study estimated that more than 80% of Ashkenazi maternal ancestry comes from women indigenous to (mainly prehistoric Western) Europe, and only 8% from the Near East, while the origin of the remainder is undetermined.[17][177] According to the study this "point to a significant role for the conversion of women in the formation of Ashkenazi communities."[17][18][179][180][181] Karl Skorecki criticized the study, arguing that while it "re-opened the question of the maternal origins of Ashkenazi Jewry, the phylogenetic analysis in the manuscript does not 'settle' the question."[182]

A 2014 study by Fernández et al. found that Ashkenazi Jews display a frequency of haplogroup K in their maternal DNA, suggesting an ancient Near Eastern matrilineal origin, similar to the results of the Behar study in 2006. Fernández noted that this observation clearly contradicts the results of the 2013 study led by Richards that suggested a European source for 3 exclusively Ashkenazi K lineages.[39]

Association and linkage studies (autosomal DNA)

In genetic epidemiology, a genome-wide association study (GWA study, or GWAS) is an examination of all or most of the genes (the genome) of different individuals of a particular species to see how much the genes vary from individual to individual. These techniques were originally designed for epidemiological uses, to identify genetic associations with observable traits.[183]

A 2006 study by Seldin et al. used over 5,000 autosomal SNPs to demonstrate European genetic substructure. The results showed "a consistent and reproducible distinction between 'northern' and 'southern' European population groups". Most northern, central, and eastern Europeans (Finns, Swedes, English, Irish, Germans, and Ukrainians) showed >90%, while most southern Europeans (Italians, Greeks, Portuguese, Spaniards) showed >85%. Both Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews showed >85% membership in the "southern" group. Referring to the Jews clustering with southern Europeans, the authors state the results were "consistent with a later Mediterranean origin of these ethnic groups".[16]

A 2007 study by Bauchet et al. found that Ashkenazim were most closely clustered with Arabic North African populations than with the global population, and in the European structure analysis, they share similarities only with Greeks and Southern Italians, reflecting their east Mediterranean origins.[184][185]

A 2010 study of Jewish ancestry by Atzmon-Ostrer et al. identified two major groups: Middle Eastern Jews and European/Syrian Jews, by using "principal component, phylogenetic, and identity by descent (IBD) analysis". "The IBD segment sharing and the proximity of European Jews to each other and to southern European populations suggested similar origins for European Jewry and refuted large-scale genetic contributions of Central and Eastern European and Slavic populations to the formation of Ashkenazi Jewry", as the two groups share ancestors in the Middle East about 2500 years ago. The study examines genetic markers spread across the entire genome and finds that the Jewish groups (Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi) share large swaths of DNA, indicating close relationships, and that each studied Jewish group (Iranian, Iraqi, Syrian, Italian, Turkish, Greek and Ashkenazi) has its own genetic signature but is more closely related to the other Jewish groups than to their fellow non-Jewish countrymen.[186] Atzmon's team found that the SNP markers in genetic segments of 3 million DNA letters or longer were 10 times more likely to be identical among Jews than non-Jews. Results of the analysis also tally with biblical accounts of the fate of the Jews. The study also found that with respect to non-Jewish European groups, the population most closely related to Ashkenazi Jews are modern-day Italians. The study speculated that this similarity may be due to inter-marriage and conversions in during the Roman Empire. It was also found that any two Ashkenazi Jewish participants shared about as much DNA as fourth or fifth cousins.[187][188]

A 2010 study by Bray et al., using SNP microarray techniques and linkage analysis, found that when assuming Druze and Palestinian Arab populations to represent the reference to world Jewry ancestor genome, 35% to 55% of the modern Ashkenazi genome may be of European origin, and that European "admixture is considerably higher than previous estimates by studies that used the Y chromosome" with this reference point.[189] The authors interpreted this linkage disequilibrium in the Ashkenazi Jewish population as matching signs "of interbreeding or 'admixture' between Middle Eastern and European populations".[190] On the Bray et al. tree, Ashkenazi Jews were found to be a genetically more divergent population than Russians, Orcadians, French, Basques, Sardinians, Italians and Tuscans. The study also observed that Ashkenazim are more diverse than their Middle Eastern relatives, which was counterintuitive because Ashkenazim are supposed to be a subset, not a superset, of their assumed geographical source population. Bray et al. therefore suggest that these results reflect a history of mixing between genetically distinct populations in Europe. However, it is possible that Ashkenazim's high heterozygocity was due to a relaxation of marriage prescription in their ancestors, while the low heterozygocity in te Middle East is due to maintenance of FBD marriage there. Therefore, Ashkenazim distinctiveness as found in the Bray et al. study may come from their ethnic endogamy (ethnic inbreeding), which allowed them to "mine" their ancestral gene pool in the context of relative reproductive isolation from European neighbors, and not from clan endogamy (clan inbreeding). Consequently, their higher diversity compared to Middle Easterners stems from the latter's marriage practices, not necessarily from the former's admixture with Europeans.[191]

A 2010 genome-wide genetic study by Behar et al. examined the genetic relationships among all major Jewish groups, including Ashkenazim, and their genetic relationship with non-Jewish ethnic populations. It found that today's Jews (except Indian and Ethiopian Jews) are closely related to people from the Levant. The authors explained that "the most parsimonious explanation for these observations is a common genetic origin, which is consistent with an historical formulation of the Jewish people as descending from ancient Hebrew and Israelite residents of the Levant".[192]

A 2013 study by Behar et al. found evidence among Ashkenazim of mixed European and Levantine origins. The authors found Ashkenazi had the greatest affinity and shared ancestry firstly with other Jewish groups from southern Europe, Syria, and North Africa, and secondly with both southern Europeans (such as Italians) and modern Levantines (such as the Druze, Cypriots, Lebanese and Samaritans). The study found no affinity of Ashkenazim to northern Caucasus populations, and no more affinity to modern south Caucasus and eastern Anatolian populations (such as Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Georgians, and Turks) than found in other Jews or non-Jewish Middle Easterners (such as the Kurds, Iranians, Druze and Lebanese).[193]

A 2017 autosomal study by Xue, Shai Carmi et al. found an admixture of Middle-Eastern and European ancestry in Ashkenazi Jews: with the European component comprising ≈50%–70% (estimated at "possibly 60%") and largely being of a southern European source and a minority eastern European, and the remainder (estimated at possibly ≈40%) being Middle Eastern ancestry showing the strongest affinity to Levantine populations such as the Druze and Lebanese.[40]

A 2018 study, referencing the popular theory of Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) origins in "an initial settlement in Western Europe (Northern France and Germany), followed by migration to Poland and an expansion there and in the rest of Eastern Europe", tested "whether Ashkenazi Jews with recent origins in Eastern Europe are genetically distinct from Western European Ashkenazi". The study concluded that "Western AJ consist of two slightly distinct groups: one that descends from a subset of the original founders [who remained in Western Europe], and another that migrated there back from Eastern Europe, possibly after absorbing a limited degree of gene flow".[194]

A 2022 study of genome data from the medieval Jewish cemetery of Erfurt found at least two related but genetically distinct Jewish groups: one closely related to Middle Eastern populations and especially similar to modern Ashkenazi Jews from France and Germany and modern Sephardic Jews from Turkey; the other group had a substantial contribution from Eastern European populations. But today Ashkenazi Jews from eastern Europe no longer exhibit this genetic variability, and instead, their genomes resemble a nearly even mixture of the two Erfurt groups (with about 60% from the first group and 40% from the second).[41]

The Khazar hypothesis

In the late 19th century, it was proposed that the core of Ashkenazi Jews were genetically descended from a hypothetical Khazarian Jewish diaspora who had migrated westward from modern Russia and Ukraine into modern France and Germany (as opposed to the currently held theory that Jews migrated from France and Germany into Eastern Europe). The hypothesis is not corroborated by historical sources,[195] and is unsubstantiated by genetics,[193] but it is still occasionally supported by scholars who have had some success in keeping the theory in the academic consciousness.[196][197]

The theory has sometimes been used by Jewish authors such as Arthur Koestler as part of an argument against traditional forms of antisemitism (for example the claim that "the Jews killed Christ"), just as similar arguments have been advanced on behalf of the Crimean Karaites. Today, however, the theory is more often associated with antisemitism[198] and anti-Zionism.[199]

A 2013 trans-genome study carried out by 30 geneticists, from 13 universities and academies, from nine countries, assembling the largest data set available to date, for assessment of Ashkenazi Jewish genetic origins found no evidence of Khazar origin among Ashkenazi Jews. The authors concluded:

Thus, analysis of Ashkenazi Jews together with a large sample from the region of the Khazar Khaganate corroborates the earlier results that Ashkenazi Jews derive their ancestry primarily from populations of the Middle East and Europe, that they possess considerable shared ancestry with other Jewish populations, and that there is no indication of a significant genetic contribution either from within or from north of the Caucasus region.

The authors found no affinity in Ashkenazim with north Caucasus populations, as well as no greater affinity in Ashkenazim to south Caucasus or Anatolian populations than that found in non-Ashkenazi Jews and non-Jewish Middle Easterners (such as the Kurds, Iranians, Druze and Lebanese). The greatest affinity and shared ancestry of Ashkenazi Jews were found to be (after those with other Jewish groups from southern Europe, Syria, and North Africa) with both southern Europeans and Levantines such as Druze, Cypriot, Lebanese and Samaritan groups.[193]

Medical genetics

There are many references to Ashkenazi Jews in the literature of medical and population genetics. Indeed, much awareness of "Ashkenazi Jews" as an ethnic group or category stems from the large number of genetic studies of disease, including many that are well reported in the media, that have been conducted among Jews. Jewish populations have been studied more thoroughly than most other human populations, for a variety of reasons:

- Jewish populations, and particularly the large Ashkenazi Jewish population, are ideal for such research studies, because they exhibit a high degree of endogamy, yet they are sizable.[200]

- Jewish communities are comparatively well informed about genetics research, and have been supportive of community efforts to study and prevent genetic diseases.[200]

The result is a form of ascertainment bias. This has sometimes created an impression that Jews are more susceptible to genetic disease than other populations.[200] Healthcare professionals are often taught to consider those of Ashkenazi descent to be at increased risk for colon cancer.[201] People of Ashkenazi descent are at much higher risk of being a carrier for Tay–Sachs disease, which is fatal in its homozygous form.[202]

Genetic counseling and genetic testing are often undertaken by couples where both partners are of Ashkenazi ancestry. Some organizations, most notably Dor Yeshorim, organize screening programs to prevent homozygosity for the genes that cause related diseases.[203][204]

See also

Explanatory notes

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 "Ashkenazi Jews". Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- 1 2 "First genetic mutation for colorectal cancer identified in Ashkenazi Jews". The Gazette. Johns Hopkins University. 8 September 1997. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ Feldman, Gabriel E. (May 2001). "Do Ashkenazi Jews have a Higher than expected Cancer Burden? Implications for cancer control prioritization efforts". Israel Medical Association Journal. 3 (5): 341–46. PMID 11411198. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ Statistical Abstract of Israel, 2009, CBS. "Table 2.24 – Jews, by country of origin and age". Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Yiddish". 19 November 2019. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Reconstruction of Patrilineages and Matrilineages of Samaritans and Other Israeli Populations From Y-Chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Jews Are the Genetic Brothers of Palestinians, Syrians, and Lebanese". Science Daily. 9 May 2000. Archived from the original on 19 June 2000. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "Study Finds Close Genetic Connection Between Jews, Kurds". Haaretz. 21 November 2001. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- 1 2 Ben-Sasson 1976.

- 1 2 Doron M. Behar; Mait Metspalu; Yael Baran; Naama M. Kopelman; Bayazit Yunusbayev; Ariella Gladstein; Shay Tzur; Hovhannes Sahakyan; Ardeshir Bahmanimehr; Levon Yepiskoposyan; Kristiina Tambets; Elza K. Khusnutdinova; Alena Kushniarevich; Oleg Balanovsky; Elena Balanovsky (2013). "No Evidence from Genome-wide Data of a Khazar Origin of the Ashkenazi Jews". Human Biology. 85 (6): 859–900. doi:10.13110/humanbiology.85.6.0859. ISSN 0018-7143. PMID 25079123.

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (9 June 2010). "Studies Show Jews' Genetic Similarity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ "High-resolution Y chromosome haplotypes of Israeli and Palestinian Arabs reveal geographic substructure and substantial overlap with haplotypes of Jews" (PDF). Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ "Banda et al. "Admixture Estimation in a Founder Population". Am Soc Hum Genet, 2013". Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ↑ Bray, SM; Mulle, JG; Dodd, AF; Pulver, AE; Wooding, S; Warren, ST (September 2010). "Signatures of founder effects, admixture, and selection in the Ashkenazi Jewish population". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (37): 16222–27. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10716222B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1004381107. PMC 2941333. PMID 20798349.

- ↑ Adams SM, Bosch E, Balaresque PL, et al. (December 2008). "The genetic legacy of religious diversity and intolerance: paternal lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula". American Journal of Human Genetics. 83 (6): 725–36. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.007. PMC 2668061. PMID 19061982.

- 1 2 Seldin MF, Shigeta R, Villoslada P, et al. (September 2006). "European population substructure: clustering of northern and southern populations". PLOS Genet. 2 (9): e143. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020143. PMC 1564423. PMID 17044734.

- 1 2 3 M. D. Costa and 16 others (2013). "A substantial prehistoric European ancestry amongst Ashkenazi maternal lineages". Nature Communications. 4 (1): 2543. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2543C. doi:10.1038/ncomms3543. PMC 3806353. PMID 24104924.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 "Jewish Women's Genes Traced Mostly to Europe – Not Israel – Study Hits Claim Ashkenazi Jews Migrated From Holy Land". The Jewish Daily Forward. 12 October 2013. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ↑ Shai Carmi; Ken Y. Hui; Ethan Kochav; Xinmin Liu; James Xue; Fillan Grady; Saurav Guha; Kinnari Upadhyay; Dan Ben-Avraham; Semanti Mukherjee; B. Monica Bowen; Tinu Thomas; Joseph Vijai; Marc Cruts; Guy Froyen; Diether Lambrechts; Stéphane Plaisance; Christine Van Broeckhoven; Philip Van Damme; Herwig Van Marck; et al. (September 2014). "Sequencing an Ashkenazi reference panel supports population-targeted personal genomics and illuminates Jewish and European origins". Nature Communications. 5 (1): 4835. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4835C. doi:10.1038/ncomms5835. PMC 4164776. PMID 25203624.

- 1 2 Wells, John (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ↑ Ashkenaz, based on Josephus. AJ. 1.6.1., Perseus Project AJ1.6.1, . and his explanation of Genesis 10:3, is considered to be the progenitor of the ancient Gauls (the people of Gallia, meaning, mainly the people from modern France, Belgium, and the Alpine region) and the ancient Franks (of, both, France, and Germany). According to Gedaliah ibn Jechia the Spaniard, in the name of Sefer Yuchasin (see: Gedaliah ibn Jechia, Shalshelet Ha-Kabbalah Archived 13 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Jerusalem 1962, p. 219; p. 228 in PDF), the descendants of Ashkenaz had also originally settled in what was then called Bohemia, which today is the present-day Czech Republic. These places, according to the Jerusalem Talmud (Megillah 1:9 [10a], were also called simply by the diocese "Germamia". Germania, Germani, Germanica have all been used to refer to the group of peoples comprising the Germanic tribes, which include such peoples as Goths, whether Ostrogoths or Visigoths, Vandals and Franks, Burgundians, Alans, Langobards, Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Suebi and Alamanni. The entire region east of the Rhine river was known by the Romans as "Germania" (Germany).

- 1 2 Mosk, Carl (2013). Nationalism and economic development in modern Eurasia. New York: Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-415-60518-2.

In general the Ashkenazi originally came out of the Holy Roman Empire, speaking a version of German that incorporates Hebrew and Slavic words, Yiddish.

- ↑ Mosk (2013), p. 143. "Encouraged to move out of the Holy Roman Empire as persecution of their communities intensified during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the Ashkenazi community increasingly gravitated toward Poland."

- ↑ Harshav, Benjamin (1999). The Meaning of Yiddish. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 6. "From the fourteenth and certainly by the sixteenth century, the center of European Jewry had shifted to Poland, then ... comprising the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (including today's Byelorussia), Crown Poland, Galicia, the Ukraine and stretching, at times, from the Baltic to the Black Sea, from the approaches to Berlin to a short distance from Moscow."

- 1 2 Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "ShUM cities of Speyer, Worms and Mainz". whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ↑ Ben-Sasson, Haim Hillel; et al. (2007). "Germany". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 7 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. pp. 526–28. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

The cultural and intellectual reorientation of the Jewish minority was closely linked with its struggle for equal rights and social acceptance. While earlier generations had used solely the Yiddish and Hebrew languages among themselves, ... the use of Yiddish was now gradually abandoned, and Hebrew was by and large reduced to liturgical usage.

- ↑ Henry L. Feingold (1995). Bearing Witness: How America and Its Jews Responded to the Holocaust. Syracuse University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8156-2670-1. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ Eric Hobsbawm (2002). Interesting Times: A Twentieth Century Life. Abacus Books. p. 25.

- ↑ Abramson, Glenda (March 2004). Encyclopedia of Modern Jewish Culture. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-134-42864-9.

- ↑ Blanning, T. C. W. (2000). The Oxford History of Modern Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285371-4.

- 1 2 3 Brunner, José (2007). Demographie – Demokratie – Geschichte: Deutschland und Israel (in German). Wallstein Verlag. p. 197. ISBN 978-3-8353-0135-1. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ↑ Rafael, Eliezer Ben; Gorni, Yosef; Ro'i, Yaacov (2003). Contemporary Jewries: Convergence and Divergence. Brill. p. 186. ISBN 978-90-04-12950-4. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ Ehrlich, M. Avrum (2009). Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 193ff [195]. ISBN 978-1-85109-873-6. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ "Jewish Population of Europe in 1933: Population Data by Country". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- 1 2 Sergio DellaPergola (2008). ""Sephardic and Oriental" Jews in Israel and Countries: Migration, Social Change, and Identification". In Peter Y. Medding (ed.). Sephardic Jewry and Mizrahi Jews. Vol. X11. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–42. ISBN 978-0-19-971250-2. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2015. Della Pergola does not analyze or mention the Ashkenazi statistics, but the figure is implied by his rough estimate that in 2000, Oriental and Sephardi Jews constituted 26% of the population of world Jewry.

- 1 2 Focus on Genetic Screening Research, ed. Sandra R. Pupecki, p. 58

- 1 2 Costa, Marta D.; Pereira, Joana B.; Pala, Maria; Fernandes, Verónica; Olivieri, Anna; Achilli, Alessandro; Perego, Ugo A.; Rychkov, Sergei; Naumova, Oksana; Hatina, Jiři; Woodward, Scott R.; Eng, Ken Khong; Macaulay, Vincent; Carr, Martin; Soares, Pedro; Pereira, Luísa; Richards, Martin B. (8 October 2013). "A substantial prehistoric European ancestry amongst Ashkenazi maternal lineages". Nature Communications. 4 (1): 2543. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2543C. doi:10.1038/ncomms3543. PMC 3806353. PMID 24104924.

- 1 2 3 Behar, Doron M.; Ene Metspalu; Toomas Kivisild; Alessandro Achilli; Yarin Hadid; Shay Tzur; Luisa Pereira; Antonio Amorim; Lluı's Quintana-Murci; Kari Majamaa; Corinna Herrnstadt; Neil Howell; Oleg Balanovsky; Ildus Kutuev; Andrey Pshenichnov; David Gurwitz; Batsheva Bonne-Tamir; Antonio Torroni; Richard Villems; Karl Skorecki (March 2006). "The Matrilineal Ancestry of Ashkenazi Jewry: Portrait of a Recent Founder Event" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 78 (3): 487–97. doi:10.1086/500307. PMC 1380291. PMID 16404693. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- 1 2 Eva Fernández; Alejandro Pérez-Pérez; Cristina Gamba; Eva Prats; Pedro Cuesta; Josep Anfruns; Miquel Molist; Eduardo Arroyo-Pardo; Daniel Turbón (5 June 2014). "Ancient DNA Analysis of 8000 B.C. Near Eastern Farmers Supports an Early Neolithic Pioneer Maritime Colonization of Mainland Europe through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands". PLOS Genetics. 10 (6): e1004401. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004401. PMC 4046922. PMID 24901650.

- 1 2 Xue J, Lencz T, Darvasi A, Pe'er I, Carmi S (April 2017). "The time and place of European admixture in Ashkenazi Jewish history". PLOS Genetics. 13 (4): e1006644. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006644. PMC 5380316. PMID 28376121.

- 1 2 Waldman, Shamam; Backenroth, Daniel; Harney, Éadaoin; Flohr, Stefan; Neff, Nadia C.; Buckley, Gina M.; Fridman, Hila; Akbari, Ali; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Olalde, Iñigo; Cooper, Leo; Lomes, Ariel; Lipson, Joshua; Cano Nistal, Jorge (8 December 2022). "Genome-wide data from medieval German Jews show that the Ashkenazi founder event pre-dated the 14th century". Cell. 185 (25): 4703–4716.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.11.002. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 9793425. PMID 36455558. S2CID 248865376.

- ↑ Gmirkin, Russell (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-567-02592-0. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- 1 2 Straten, Jits van (2011). The Origin of Ashkenazi Jewry. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-023605-7. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- 1 2 Vladimir Shneider, Traces of the Ten. Beer-sheva, Israel 2002. p. 237

- ↑ Bøe, Sverre (2001). Gog and Magog: Ezekiel 38–39 as Pre-text for Revelation 19,17–21 and 20,7–10. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-147520-7. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Kriwaczek, Paul (2011). Yiddish Civilisation: The Rise and Fall of a Forgotten Nation. Orion. ISBN 978-1-78022-141-0. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ Bromiley, Geoffrey William (1964). Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2249-9. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- 1 2 3 Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred, eds. (2007). "Ashkenaz". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. pp. 569–71. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.