The Arctic policy of Russia is the domestic and foreign policy of the Russian Federation with respect to the Russian region of the Arctic. The Russian region of the Arctic is defined in the "Russian Arctic Policy" as all Russian possessions located north of the Arctic Circle. Approximately one-fifth of Russia's landmass is north of the Arctic Circle. Russia is one of five littoral states bordering the Arctic Ocean[lower-alpha 1]. As of 2010, out of 4 million inhabitants of the Arctic, roughly 2 million lived in arctic Russia, making it the largest arctic country by population. However, in recent years Russia's Arctic population has been declining at an excessive rate.[2]

The stated goals of Russia in its Arctic policy are to utilize its natural resources, protect its ecosystems, use the seas as a transportation system in Russia's interests, and ensure that it remains a zone of peace and cooperation.[3] Russia currently maintains a military presence in the Arctic and has plans to expand it, as well as strengthen the Border Guard/Coast Guard presence there. Using the Arctic for economic gain has been done by Russia for centuries for shipping and fishing. Russia has plans to exploit the large offshore resource deposits in the Arctic. The Northern Sea Route is of particular importance to Russia for transportation, and the Russian Security Council is considering projects for its development. The Security Council also stated a need for increasing investment in Arctic infrastructure.[4]

Russia conducts extensive research in the Arctic region, notably the drifting ice stations and the Arktika 2007 expedition, which was the first to reach the seabed at the North Pole. The research is partly aimed to back up Russia's territorial claims, specifically those related to Russia's extended continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean.

History

On October 1, 1987, Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, delivered the Murmansk Initiative stating six goals of the Soviet Union's Arctic foreign policy: establish a nuclear-free zone in Northern Europe; reduce military activity in the Baltic, Northern, Norwegian and Greenland Seas; cooperate on resource development; form an international conference on Arctic scientific research coordination; cooperate in environmental protection and management; and open the Northern Sea Route.[5]

Geography

|

The Russian Ministry of Economic Development has identified eight Arctic Support Zones along the Arctic coast of Russia on which funds and projects will be focused, with the aim of fostering the economic potential of the Northern Sea Route while ensuring that the Russian presence will not be limited to resource extraction.[6][7]

The eight zones are Kola, Arkhangelsk, Nenets, Vorkuta, Yamal-Nenets, Taimyr-Turukhan, North Yakutia and Chukotka.[8] In the North Yakutia area, the project includes reconstruction of the Tiksi sea port and the port of Zelenomysky.[9] In the Arkhangelsk zone, this will include the construction of the Belkomur Railway.[10]

Exploration

The first recorded voyage to the Russian Arctic was by the Novgorodian Uleb in 1032, in which he discovered the Kara Sea. From the 11th to the 16th centuries, Russian coastal dwellers of the White Sea, or pomors, gradually explored other parts of the Arctic coastline, going as far as the Ob and Yenisey rivers, establishing trading posts in Mangazeya. Continuing the search of furs and walrus and mammoth ivory, the Siberian Cossacks under Mikhail Stadukhin reached the Kolyma River by 1644. Ivan Moskvitin discovered the Sea of Okhotsk in 1639 and Fedot Alekseyev Popov and Semyon Dezhnyov discovered the Bering Strait in 1648,[11] with Dezhnyov establishing a permanent Russian settlement near the present day Anadyr.

After Peter I took the throne, Russia began to develop a navy and use it to continue its Arctic exploration. Vitus Bering explored Kamchatka in 1728,[11] while Bering's aides Ivan Fyodorov and Mikhail Gvozdev discovered Alaska in 1732. The Great Northern Expedition, which lasted from 1733 to 1743, was one of the largest exploration enterprises in history, organized and led by Vitus Bering, Aleksei Chirikov and a number of other major explorers. A party of the expedition personally led by Bering and Chirikov discovered southern Alaska, the Aleutian Islands and the Commander Islands,[12] while the parties led by Stepan Malygin, Dmitry Ovtsyn, Fyodor Minin, Semyon Chelyuskin, Vasily Pronchischev, Khariton Laptev and Dmitry Laptev mapped most of the Arctic coastline of Russia (from the White Sea in Europe to the mouth of Kolyma River in Asia).[13] The expedition resulted in 62 large maps and charts of the Arctic region.[12]

Territorial claims

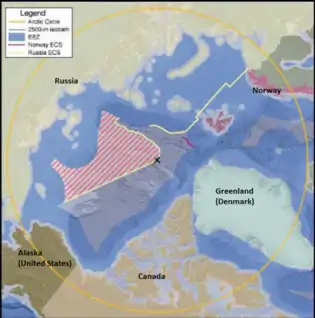

Modern Russian territorial claims to the Arctic officially date back to April 15, 1926, when the Soviet Union claimed land between 32°04'35"E and 168°49'30"W. However, this claim specifically only applied to islands and lands within this region.[14] The first maritime boundary between Russia and Norway, from the Varangerfjord, was signed in 1957. However, tensions resurfaced after both countries made continental shelf claims in the 1960s.[15] Informal talks began in the 1970s about determining a boundary in the Barents Sea to settle differing claims,[15] as Russia wanted the boundary to be a line running straight north from the mainland, 67,000 square miles (170,000 km2) more than what it had. On September 15, 2010, Foreign Ministers Jonas Gahr Støre and Sergei Lavrov, of Norway and Russia respectively, signed a treaty that effectively divided the disputed territory in half between the two countries, and also agreed to co-manage resources in that region where they overlap national sectors.[16][17][18] The two countries had already been co-managing fisheries in the Barents since the 1978 Grey Zone Agreement, which has been renewed annually since it was signed.[15][18]

On March 12, 1997, Russia ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which allowed countries to make claims to extended continental shelves.[19] In accordance with UNCLOS, Russia submitted a claim to an extended continental shelf beyond its 200-mile (320 km) exclusive economic zone on December 20, 2001, to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). Russia claimed that two underwater mountain chains - the Lomonosov and Mendeleev ridges - within the Russian sector of the Arctic were extensions of the Eurasian continent and thus part of the Russian continental shelf. The UN CLCS neither validated nor invalidated the claim but requested Russia to submit additional data to substantiate its claim.[20] Russia planned to submit additional data to the CLCS in 2012.[21]

In August 2007, a Russian expedition named Arktika 2007, led by Artur Chilingarov, planted a Russian flag on the seabed at the North Pole.[22] This was done in the course of scientific research to substantiate Russia's 2001 extended continental shelf claim submission.[22] Rock, mud, water, and plant samples at the seabed were collected and brought back to Russia for scientific study.[23] The Natural Resources Ministry of Russia announced that the bottom samples collected from the expedition are similar to those found on continental shelves. Russia is using this to substantiate its claim that the Lomonosov Ridge in its sector is a continuation of the continental shelf that extends from Russia, and that Russia has a legitimate claim to that seabed.[24] The United States and Canada dismissed the flag planting as purely symbolic and legally meaningless.[25] Russia's Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov agreed,[18] telling reporters: "The aim of this expedition is not to stake Russia's claim but to show that our shelf reaches to the North Pole."[26] He also confirmed that Arctic territory issues "can be tackled solely on the basis of international law, the International Convention on the Law of the Sea and in the framework of the mechanisms that have in accordance with it been created for determining the borders of states which have a continental shelf."[27] In another interview Sergey Lavrov said: "I was amazed by my Canadian counterpart’s statement that we are planting flags around. We’re not throwing flags around. We just do what other discoverers did. The purpose of the expedition is not to stake whatever rights of Russia, but to prove that our shelf extends to the North Pole. By the way the flag on the Moon, it was the same".[28]

Foreign Ministers and other officials representing Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the United States met in Ilulissat, Greenland in May 2008, at the Arctic Ocean Conference and announced the Ilulissat Declaration. Among other things the declaration stated that any demarcation issues in the Arctic should be resolved on a bilateral basis between contesting parties.[29][30]

An example of such bilateral agreement was achieved between Russia and Norway in 2010.

Military

Part of Russia's current Arctic policy includes maintaining a military presence in the region. In 2014, the Northern Fleet Joint Strategic Command (Russia) was established. The Russian Northern Fleet, the largest of the four Russian Navy fleets, is headquartered in Severomorsk, in the Kola Gulf on the Barents Sea.[31] The Northern Fleet encompasses two-thirds of Russia's total naval power, and has close to 80 operational ships.[32] As of 2013, this included approximately 35 submarines, six missile cruisers, and the flagship Petr Velikiy (Peter the Great), a nuclear-powered guided missile cruiser.[32] In 2012 the Russian Navy resumed naval patrols of the Northern Sea Route, marked by a 2,000 mile patrol of the Russian Arctic by ten ships led by an icebreaker and the Petr Velikiy.[33] The Russian Military also reportedly announced in June 2008 that it would increase the operational radius of its Northern Fleet submarines.[34]

The first nuclear icebreaker, the Lenin, began operating in the Northern Sea Route in July 1960.[35] A total of ten nuclear-powered civilian vessels, including nine icebreakers, have been built in Russia. Three of these have been decommissioned, including the Lenin.[36] Besides its six nuclear icebreakers, Russia also has 19 diesel polar icebreakers.[37] Its nuclear icebreaker fleet includes the 50 Let Pobedy (50 Years of Victory), the largest nuclear icebreaker in the world.[32] There are currently plans to build six more icebreakers, as well as plans to build a $33 billion year-round Arctic port.[38] On September 28, 2011, President Medvedev lifted the ban on the privatization of the nuclear icebreaker fleet with decree No. 1256.[36] This repeal will allow Atomflot, the state company that owns the fleet, to be at least partially owned by private investors. The government is expected to retain a controlling share in the company.[39]

Russia says that it has military units specifically trained for Arctic combat.[34] On October 4, 2010, Russian Navy commander Admiral Vladimir Vysotsky was quoted as saying: "We are observing the penetration of a host of states which . . . are advancing their interests very intensively, in every possible way, in particular China," and that Russia would "not give up a single inch" in the Arctic. [40] Russian Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov announced plans on July 16, 2011, for the creation of two brigades that would be stationed in the Arctic.[41] Russia's Arctic policy statement, approved by President Medvedev on September 18, 2008, called for the establishment of improved military forces in the Arctic to "ensure military security" in that region, as well as the strengthening of existing border guards in the area.[3][42]

Research

Russia has conducted research in the Arctic for decades. The country is the only one that uses drift stations- research facilities seasonally deployed on drift ice- and also has other research stations in its Arctic zone. The first drift station, North Pole-1, was established on May 21, 1937, by the Soviet Union.[43] Russian research has focused on the Arctic seabed, marine life, meteorology, exploration, and natural resources, among other topics. Recent research has also been focusing on studying the Lomonosov Ridge to collect evidence that could strengthen Russian territorial claims to the seabed in that region within the Russian sector of the Arctic.[43][44]

Drifting station North Pole-38 was established in October 2010.[45] In July 2011 the icebreaker Rossiya and the research ship Akademik Fyodorov began conducting seismic studies north of Franz Josef Land to find evidence to back up Russia's territorial claims in the Arctic. The Akademik Fyodorov and the icebreaker Yamal went on a similar mission the year before. The Lena-2011 expedition, a joint Russian-German project headed by Jörn Thiede, left for the Laptev Sea and the Lena River in the summer of 2011. It was to study Siberian climate and climate change, as well as gather information about the Russian continental shelf.[46] The head of the expedition, who is also the chairman of the European Arctic Commission, expressed confidence that Russia will gather the evidence needed to confirm its claim to additional parts of the Arctic shelf.[47]

In 2011, research stations under construction included one on Samoylovsky Island, which was planned to be completed by mid-2012 and will focus on researching shelf zone permafrost,[48] and one on the Svalbard Islands, which was anticipated to be finished in 2013 and will focus on geophysical, hydrological, and geological research.[49]

Over the summer of 2015, Russia built a large Federal Security Service (Russ. FSB) Border Guard base on Alexandra Land island of the Franz Joseph Land archipelago, expanding on an already established airbase called Nagurskoye, above the 80th parallel. The new complex is made of multiple inter-connected buildings and can house a company of 150 soldiers for up to 18 months without the need of re-supply.[50]

Economy

Russia's economic interests in the Arctic are based on two things - natural resources and maritime transport.[51] The Northern Sea Route, in use for centuries and officially defined by Russian legislation, is an Arctic shipping lane that stretches from the Barents Sea to the Bering Strait through Arctic waters. Travel along Northern Sea Route takes only one-third the distance needed to go through the Suez Canal, without as high a risk of pirates.[52]

The route is currently open for up to eight weeks a year, and studies are predicting that climate change will lead to further reduction in Arctic ice, which can lead to greater use of the route.[53][54] Even when "open" this route is not totally ice free and requires Russian icebreaker and navigational support to ensure safety of passage. Currently 1.5 million tonnes (1,500,000 long tons; 1,700,000 short tons) of goods are transported along the Northern Sea Route every year.[53] Traffic through the Route is expected to increase tenfold by 2020, and six tankers have already gone through in 2010.[52] The Russian government estimates that annual cargo traffic could reach 85 million metric tons,[55] and shipping along the Route could account for a quarter of cargo between Europe and Asia by 2030.[56] However, using the Northern Sea Route extensively will require vast expansion of Russia's current infrastructure in the Arctic, especially ports and naval vessels.[53] In August 2011 Nikolai Patrushev, Secretary of Russia's Security Council, stated that the poor condition of infrastructure in the Arctic hinders development there, reducing the attractiveness of the region's resources for development.[4] The infrastructure is worse in the eastern part of Russia, which also contains more resources.[4] Recent economic sanctions imposed on Russia have additionally weakened the NSR's viability for foreign investors and in 2014 the overall number of voyages across the passage has fallen dramatically from 71 to 53.[57]

The Yamal Peninsula, home to Russia's biggest natural gas reserves, was connected to the rest of Russia by Gazprom through the creation of the Obskaya–Bovanenkovo Line, which opened in 2010. This was part of Gazprom's Yamal project to develop natural gas resources in the Yamal Peninsula.[58] Russian Railways plans to connect Indiga, which is being considered as a prime location for the construction of a deepwater port, and Amderma, site of the Amderma Airport, to its railway system by 2030.[52] Prime Minister Putin also announced that a year-round port would be constructed on the Yamal Peninsula.[59]

But so far, Russia's concentration on production of oil and gas on the Yamal Peninsula met with huge challenges.[60] In attempting to extract gas and oil in the Arctic region, Gazprom encounter harsh climate and the long lines of communication. So Gazprom requires large investments with high risk and a long investment horizon and is dependent on the energy prices continuing to be high so that the extraction is profitable. International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the majority of the Arctic fields are not profitable if the world market price of oil is below 120 dollars per barrel. At the time of this writing (May 11, 2017), the price of Brent oil has fallen to around 50 dollars per barrel. Meanwhile, since Russian law only allows for the state energy companies Gazprom (mainly gas) and Rosneft (mainly oil) to extract oil and gas from the continental shelf – but since these two firms do not have at their own disposal the necessary technological expertise – they have entered into partnerships with a number of foreign firms.[60]

The Russian Government is also attempting to increase foreign investment in its Arctic resources. In August 2011 Rosneft, a Russian government-operated oil company, signed a deal with ExxonMobil in which Rosneft received some of Exxon's global oil assets in exchange for the joint development of Russian Arctic resources by both companies.[61] This agreement includes a $3.2 billion hydrocarbon exploration of the Kara and Black seas (although the Black Sea is not in the Arctic),[62] as well as the joint development of ice-resistant drilling platforms and other Arctic technologies.[63] This deal followed a failed attempt at a similar cooperation between Rosneft and BP in May.[61] Chevron is currently in talks with Rosneft about jointly developing Arctic resources.[64]

Russia is the only country in the world planning to use floating nuclear power plants. The Akademik Lomonosov, expected to go into operation in 2012, will be one of eight plants that will provide power to Russian coastal cities. There are plans for these plants to also provide power to large gas rigs in the Arctic Ocean in the future.[65][66] The Prirazlomnoye field, an offshore oilfield in the Pechora Sea that will include up to 40 wells, is currently under construction and drilling is expected to start in early 2012. It will be the world's first ice-resistant oil platform and will also be the first offshore Arctic platform.[67][68]

Russia wants to establish its Arctic possessions as a major resource base by 2020.[44][69] As climate change makes the Arctic areas more accessible, Russia, along with other countries, is looking to use the Arctic to increase its energy resource production.[70] According to the U.S. Geological Survey, there are 90 billion barrels (1.4×1010 m3) of oil and 1,670 trillion cubic feet (4.7×1013 m3) of natural gas north of the Arctic Circle.[70][71] Overall, about 10% of the world's petroleum resources are estimated to be in the Arctic. The dominant portion of offshore Arctic hydrocarbon (oil and gas), as reflected in the USGS studies, is located within the current uncontested Exclusive Economic Zones of the five nations bordering the Arctic.[72]

In September 2013, Gazprom's oil drilling activities in the Arctic have drawn protests from environmental groups particularly Greenpeace. Greenpeace has opposed oil drilling in the Arctic on the grounds that oil drilling would cause damage to the Arctic ecosystem and that there are no safety plans in place to prevent oil spills.[73] On September 18, the Greenpeace vessel MV Arctic Sunrise staged a protest and attempted to board Gazprom's Prirazlomnaya platform. In response, the Russian Coast Guard seized control of the ship, and arrested the activists. Phil Radford, executive director of Greenpeace USA, stated that the arrest of the Arctic 30 is the stiffest response that Greenpeace has encountered from a government since the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior in 1985 by the "action" branch of the French foreign intelligence services, the Direction générale de la sécurité extérieure (DGSE).[74] Earlier in August 2012, Greenpeace had also staged similar protests against the same oil rig.[75][76] The Russian government has intended to charge the Greenpeace activists with piracy, which carries a maximum penalty of fifteen years of imprisonment.[73] Thirty members of the crew of "Arctic Sunrise" have been detained for 48 hours by authorities in Murmansk. The crew members come from 19 countries. Several members were arrested after having assaulted the Prirazlomnaya drill rig in the Pechora Sea.[77]

See also

References

- ↑ "Iceland".

- ↑ "Socio-demographic situation in the Arctic". Archived from the original on 2012-03-17. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- 1 2 "Russia's Arctic Policy To 2020 And Beyond". Archived from the original on 2011-12-04. Retrieved 2011-07-18.

- 1 2 3 "RF ready to contribute to preserving unique Arctic nature - Medvedev". ITAR-TASS News Agency. August 6, 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-09-14. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ↑ "Arctic - How Gorbachev shaped future Arctic policy 25 years ago". Archived from the original on 2013-06-09. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Technology and government's hand vital for Russian Arctic development". bne IntelliNews. Archived from the original on 2017-04-07. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ "Russia's Ministry of Economic Development wants 210 billion rubles for Arctic regions". Eye on the Arctic. 7 March 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ "About 40 Arctic projects may be in Russia's Yamal backbone zone — governor". TASS (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2017-04-07. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ "5 billion for development of Tiksi infrastructure". The Independent Barents Observer. Archived from the original on 2017-04-07. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ "В Минэкономразвития рассмотрели проекты 3 пилотных опорных зон развития арктической зоны РФ" (in Russian). Neftegaz. Archived from the original on 2017-04-07. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- 1 2 Leonid Sverdlov (November 27, 1996). "Russian Naval Officers and Geographic Exploration in Northern Russia (18th through 20th centuries)". Arctic Voice. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- 1 2 "The Great Northern Expedition". Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment Working Group. Archived from the original on 2012-01-29. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Russian Northern Expeditions (18th-19th centuries)". Beaufort Gyre Exploration Project. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Leonid Timtchenko (June 17, 1996). "The Russian Arctic Sectoral Concept: Past And Present" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- 1 2 3 Thilo Neumann (November 9, 2010). "Norway and Russia Agree on Maritime Boundary in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean" (PDF). The American Society of International Law. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- ↑ Walter Gibbs (April 27, 2010). "Russia and Norway Reach Accord on Barents Sea". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- ↑ "Treaty on maritime delimitation and cooperation in the Barents Sea and the Arctic Ocean signed today". The Norwegian Mission to the EU. September 15, 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-11-23. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- 1 2 3 Michael Byers (April 30, 2010). "It's time to resolve our Arctic differences". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- ↑ "Status of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea" (PDF). United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-11-17. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Marc Benitah (November 8, 2007). "Russia's Claim in the Arctic and the Vexing Issue of Ridges in UNCLOS". American Society of International Law. Archived from the original on 2011-03-15. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Russian shelf claim to UN in 2012". Barents Observer. July 6, 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- 1 2 William J. Broad (February 19, 2008). "Russia's Claim Under Polar Ice Irks American". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2012-11-10. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Mike McDowell, Peter Batson. "Last of the Firsts: Diving to the Real North Pole" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Arctic seabed 'belongs to Russia'". BBC News. September 20, 2007. Archived from the original on 2010-03-25. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Mike Eckel (August 8, 2007). "Russia defends North Pole flag-planting". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ Russia plants flag on Arctic floor Archived 2012-11-02 at the Wayback Machine. CNN News.

- ↑ Lavrov, Sergey (2007-08-03). "Transcript of Remarks and Replies to Media Questions by Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov Following His Participation in the 14th Session of the ASEAN Regional Forum on Security, Manila, Philippines, August 2, 2007". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia. Archived from the original on 2009-11-13. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ↑ "Cold War Goes North - Kommersant Moscow". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ "Conference in Ilulissat, Greenland: Landmark political declaration on the future of the Arctic". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. 2008-05-28. Archived from the original on 2008-06-15. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ↑ "The Ilulissat Declaration" (PDF). um.dk. 2008-05-28. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-06-26. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ↑ Dr. Richard Weitz (February 12, 2011). "Russia: The Non-Reluctant Arctic Power". Second Line of Defense. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- 1 2 3 Marlene Laruelle (2014). Russia's Arctic Strategies and the Future of the Far North. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

- ↑ Fred Weir (September 16, 2013). "Russian Navy returns to Arctic. Permanently". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 2014-01-04. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- 1 2 Adrian Blomfield (June 11, 2008). "Russia plans Arctic military build-up". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2012-09-28. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Lawson W Brigham. "Soviet Arctic Marine Transportation". Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- 1 2 "Medvedev privatizes Russian icebreaker fleet". RIA Novosti. October 4, 2011. Archived from the original on 2014-01-04. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ Carey Restino (January 13, 2012). "Icebreaker fleet in U.S. lags behind". The Arctic Sounder. Archived from the original on 2012-03-02. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ Fred Weir (August 14, 2011). "Russia's Arctic 'sea grab'". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 2012-03-04. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "Russia to privatize its nuclear-powered icebreaker fleet". The Voice of Russia. April 10, 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ↑ "FU.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Staff Research Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-02. Retrieved 2012-10-04.

- ↑ Mia Bennett (July 4, 2011). "Russia, Like Other Arctic States, Solidifies Northern Military Presence". Foreign Policy Association. Archived from the original on 2011-08-08. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Russia plans to create Arctic military force". NBC News. March 27, 2009. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- 1 2 "North Pole Drifting Stations (1930s-1980s)". Beaufort Gyre Exploration Project. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- 1 2 "Russia to boost Arctic research". September 23, 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ "North Pole-38 keeps on drifting". The Voice of Russia. December 15, 2010. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ "Arctic shelf prospecting in view of global warming". The Voice of Russia. July 21, 2011. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ↑ "Russia likely to achieve Arctic shelf ambitions". The Voice of Russia. July 20, 2011. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ↑ "Russia planning to launch a new research station in the Arctic". Russian Geographical Society. January 18, 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-03-17. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ "Russia Plans to Build Research Center on Svalbard by 2014". RIA Novosti. February 3, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-12-04. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ "Russia asserts Arctic clout, opens large military complex on 80th parallel". The Japan Times. 2013-05-10. Archived from the original on 2016-04-27. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Katarzyna Zysk (September 2008). "Russia, Norway and the High North - past, present, future - Russian Arctic Strategy". Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies. Archived from the original on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- 1 2 3 "Future bases for the Northern Sea Route pointed out". Barents Observer. December 17, 2010. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- 1 2 3 "Sea Routes and Marine Transport". Friends of the Arctic. Archived from the original on 2012-03-28. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ "Northern Sea Routes and the Northwest Passage compared with currently used shipping routes". United Nations Environment Programme. Archived from the original on 2011-08-09. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ Nadia Rodova (September 26, 2013). "Russia's Northern Sea Route: Global Implications". Platts. Archived from the original on 2014-01-06. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ↑ Balazs Koranyi (May 29, 2013). "Arctic Shipping to Grow as Warming Opens Northern Sea Route for Longer". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 2014-01-04. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ↑ "Sanctions Dull Russia's Arctic Shipping Route Archived 2015-01-23 at the Wayback Machine" The Maritime Executive, 22 January 2015. Accessed: 23 January 2015.

- ↑ "Arctic railway launched". Barents Observer. March 3, 2011. Archived from the original on September 5, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ↑ Jeff Davis (July 6, 2011). "Russia launches Arctic expedition, beefs up military presence". Postmedia News. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- 1 2 Staun, Jørgen. “Russia’s Strategy in the Arctic. Archived 2017-05-06 at the Wayback Machine” Institute for Strategy, The Royal Danish Defence College. Copenhagen. March 2015. Web. 11 May 2017.

- 1 2 Andrew Kramer (August 30, 2011). "Exxon Reaches Arctic Oil Deal With Russians". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2011-09-08. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ↑ Melodie Warner (August 30, 2011). "Exxon Mobil, Rosneft To Jointly Develop Hydrocarbon Resources Globally". The Wall St. Journal. Archived from the original on 2012-05-23. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ↑ Roger Howard (September 4, 2011). "How Arctic oil could break new ground". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 2, 2013. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ↑ Atle Staalesen (September 5, 2011). "Rosneft prepares for Kara Sea mapping". Barents Observer. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ↑ Richard Galpin (September 22, 2010). "The struggle for Arctic riches". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2012-03-07. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ↑ Peter Fairley (July 2, 2010). "Russia Launches Floating Nuclear Power Plant". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 2011-03-22. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ↑ "Gazprom starts towing of Prirazlomnoye platform to field". iStockAnalyst. August 25, 2011. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ↑ "Prirazlmonaya sea platform to be delivered to offshore oil field". ITAR-TASS. August 26, 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2011-08-28.

- ↑ Nataliya Vasilyeva (September 20, 2010). "Russia to Boost Arctic Research Efforts". ABC News. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- 1 2 "Russia outlines Arctic force plan". BBC News. March 27, 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-10-18. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ Marsha Walton (January 2, 2009). "Countries in tug-of-war over Arctic resources". CNN. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ "USGS Arctic Oil and Gas Report". U.S. Geological Survey. July 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-09-06. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- 1 2 Shaun Walker (September 24, 2013). "Russia to charge Greenpeace activists with piracy over oil rig protest". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2013-09-25. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- ↑ Kathy Lally and Will Englund (September 27, 2013). "U.S. Greenpeace captain jailed in Russia". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2013-10-01. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Greenpeace International responds to allegations from Russian authorities". Greenpeace International. September 22, 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-10-30. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- ↑ "Armed Russian guards storm Greenpeace vessel in Arctic". Channel News Asia. September 25, 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- ↑ Interfax-AVN Moscow Online (English) 0825 GMT 25 September 2013

- ↑ "Iceland is generally not regarded as an Arctic Ocean littoral State as its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is not adjacent to the high seas portion of the Central Arctic Ocean."[1]

External links

Literature

- Kharlampieva, N. "The Transnational Arctic and Russia." In Energy Security and Geopolitics in the Arctic: Challenges and Opportunities in the 21st Century, edited by Hooman Peimani. Singapore: World Scientific, 2012

- Konyshev, Valery & Sergunin, Alexander. The Arctic at the crossroads of geopolitical interests // Russian Politics and Law, 2012. — Vol. 50, — № 2. — P. 34-54

- Konyshev, Valery & Sergunin, Alexander: Is Russia a revisionist military power in the Arctic? Defense & Security Analysis, September 2014.

- Konyshev, Valery & Sergunin, Alexander. Russia in search of its Arctic strategy: between hard and soft power? Polar Journal, April 2014.

- Devyatkin, Pavel. Russia's Arctic Strategy: aimed at conflict or cooperation? The Arctic Institute, February 2018.