| Appalachian temperate rainforest | |

|---|---|

The Appalachian Trail traverses the dense, moss-covered spruce-fir understory near the summit of Old Black in the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee |

The Appalachian temperate rainforest is located in the southern Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States. About 351,500 square kilometers (135,000 square miles) of forest land is spread across eastern Kentucky, southwestern Virginia, western North Carolina, northwestern South Carolina, northern Georgia, northern Alabama, and eastern Tennessee.[1][2] The annual precipitation is more than 60 inches (1,500 mm).[3] The Southern Appalachian spruce–fir forest is a temperate rainforest located in the higher elevations in southwestern Virginia, western North Carolina and East Tennessee.[2] Fir is dominant at higher elevation, spruce at middle elevation, and mixed forests at low elevation.[4][5][6]

Climate

The Appalachian temperate rainforest has a cool and mild climate and meets the criteria of temperate rainforests identified by Alaback.[7] Temperature and precipitation are extremely variable with elevation, with rainforest conditions usually but not always concentrated around spruce–fir forests at higher elevations.[4][9] These spruce–fir forests have an annual mean temperature of 6.5 °C (43.7 °F) and a growing season mean (May–September) of 13.5 °C (56.3 °F), though this is likely somewhat cooler than the average across the entire rainforest ecosystem.[4] It has annual precipitation above 140 centimetres (55 in), a cool summer, typical transient snow in winter, mean annual temperature near 7 °C (45 °F), and summer rainfall is above 10% of overall precipitation, classifying it as a perhumid temperate rainforest.[4][7]

Annual precipitation varies significantly within the mountainous terrain, with the highest precipitation in southwest North Carolina and the lowest near Asheville and in northeast Tennessee.[10] High altitudes hosting spruce-fir forest receive than 2,000 millimeters (79 in) of precipitation while large swaths of lower elevation rainforest receive more than 1,525 millimeters (60 in).[2][3] This pattern is primarily influenced by upslope and downslope flow of southerly winds.[10] The orographic effect causes rainfall when moist air originating in the Gulf of Mexico and western Atlantic Ocean is forced upwards by the mountains.[10][11] Winter and spring months see a gradient precipitation pattern, with higher rainfall concentrated in the south.[10] Weak upslope air flow in summer brings more precipitation to the highest elevations, while autumn is typically driest with occasional intense rainfall from tropical systems.[10]

.jpg.webp)

In addition to the increased precipitation from orographic lift, cloud cover keeps the rate of water loss low due to minimal evapotranspiration.[2] High elevation forests are immersed in clouds on 65% of growth-season days, leading some sources to describe the temperate rainforest as a cloud forest.[2] Water intercepted by clouds accounts for 25% to 50% of annual precipitation, which is a high rate.[2][4] For comparison, in the boreal rainforests of Eastern Canada, fog contributes only 5 to 8% of annual precipitation.[4] According to a tentative classification advocated by DellaSala, Alaback, Spribille, Wehrden, and Nauman in 2011, high-elevation temperate rainforest regions in Central Appalachia could be interpreted as "a southerly extension of Appalachian boreal rainforests from Eastern Canada", although this interpretation requires further study.[4]

Ecology

High precipitation levels, moderate year-round temperatures, and diverse terrain enable an incredibly wide range of species to survive.[12][13][14] The rainforest is more biodiverse than any other temperate region in the world, with over 19,000 species identified in Great Smoky Mountains National Park alone.[13][14] However, scientists estimate the real number of species may be as high as 100,000 or more.[13] It is also home to many threatened, endangered, and endemic species, including plants, arthropods, fish, mammals, mollusks, and amphibians.[13][15]

Flora

Red spruce and Fraser fir are dominant canopy trees in high mountain areas. In higher elevations (over 1,980 meters or 6,500 feet), Fraser fir is dominant; in middle elevations (1,675 to 1,890 meters or 5,495 to 6,201 feet) red spruce and Fraser fir grow together; and in lower elevation (1,370 to 1,650 meters or 4,490 to 5,410 feet) red spruce is dominant.[6] Yellow birch, mountain ash, mountain maple, younger spruce and fir and shrubs like raspberry, blackberry, hobblebush, southern mountain cranberries, red elderberry, minniebush, and southern bush honeysuckle make up the understory.[5][6][13] Below the spruce-fir forest, at around 1,200 meters (3,900 ft), forest composition shifts in favor of deciduous trees such as American beech, maple, birch, and oak.[13] American rhododendron is the dominant understory shrub throughout the deciduous layer but is only occasionally present in spruce-fir forests.[16][17] Eastern skunk cabbage and common juniper are northern species that remained in this region after glaciers retreated.[14]

In addition to over 100 species of native trees, 1,400 other flowering plants and 500 moss and fern species call the rainforest home.[14] These include a diverse array of wildflowers and dozens of fungi-reliant orchid species.[18][19] The rainforest's high humidity supports epiphytic plant species at greater height and diversity than elsewhere in the eastern United States.[20] A wide range of mosses, ferns, and liverworts have been identified as high as 140 feet (43 m) above the forest floor.[20] These include common epiphytes like resurrection fern, the endemic liverwort Bazzania nudicaulis, and some species that are solely terrestrial in the rest of their range including Appalachian rockcap fern, rose moss, and narrow-fruited crisp-moss.[20][21] Lianas are also prevalent, especially in deciduous forest, with Virginia creeper, poison ivy, and various grapevines being the most common.[17]

Fauna

The rainforest is home to the highest diversity of salamanders in the world, more than 30 species.[14] Several of these species are endemic to the region, including the black mountain salamander, southern dusky salamander, red-cheeked salamander, and Cheat Mountain salamander.[1] Many species of salamander in this area do not have lungs, so they breathe through their skin and the wet environment of rotten trees and moist leaves is conducive for their survival.[13][14]

Larger animals include the American black bear, white-tailed deer, wild turkey, and groundhog.[13][14] However, many large species once lived in the area but were extirpated by land-use and hunting changes brought about by European colonization.[13] These include bison, elk, mountain lion, gray wolf, red wolf, fisher, river otter, peregrine falcon, and several species of fish.[13] Northern species including the Carolina northern flying squirrel, American red squirrel, and saw-whet owl are relics of the Last Ice Age that survive in the area because of the cool climate.[1][13][14] Animal diversity in the rainforest is not only limited to vertebrates, however. Mollusks and millipedes reach their highest levels of biodiversity in the region, with about 150 species of land snails and 230 species of millipedes documented thus far, though species estimates for both are much higher.[13][14] It is also home to 460 arachnid species including the endangered spruce-fir moss spider, which lives nowhere else in the world.[13][14]

Funga

The wet montane environment supports one of the world’s highest diversities of fungi including lichens, sac fungi, molds, and mushrooms.[13][14] In total, over 2,300 species have been identified in the area and scientists estimate the actual number may be as high as 20,000.[13][14] Of the species discovered thus far, 800 (40%) are lichens.[13]

History

The Appalachian Mountains began to form 460 million years ago with the collision of tectonic plates, and finished their uplift around 230 million years ago.[12] During the Last Ice Age, ice covered much of northern North America, but the southern Appalachians remained ice-free.[13][14] This uncovered area acted as a refuge for species that were forced southward. After the ice receded, some species spread back north, but many stayed in the southern Appalachians.[14] Because temperature declines with increased elevation, the varying topography of the mountains forms microclimates that mimic both northern and southern latitudes. This has combined with a relatively stable year-round climate to enable northern and southern species to live in close proximity each other, lending the rainforest its high biodiversity.[13][14]

Human use

Native Americans have lived in this area for about 10,000 years. After contact with European settlers, the vast majority of the Cherokee Nation were forced to move from their traditional homeland to Oklahoma during the Trail of Tears.[22] However, about 9,000 members of the tribe continue to live inside the Qualla Boundary, which lies within the rainforest biome.[22]

Beginning with the creation of the Pisgah National Forest in 1916, much of the rainforest area now lies within public lands.[23] These include Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the Daniel Boone National Forest, Jefferson National Forest, Pisgah National Forest, Nantahala National Forest, Chattahoochee National Forest, and Cherokee National Forest. State parks incorporating Appalachian temperate rainforest include Breaks Interstate Park, Grandfather Mountain State Park, and Gorges State Park.

Threat

Anthropogenic

Air pollution is caused by anthropogenic factors, such as power plants, factories, and automobiles. It is related to acid rain and water pollution. Vegetation at high elevation easily collects pollutants. Acid rain damages the plants and makes streams more acidic. Acidic water affects aquatic species, such as fish, salamanders, and also vegetation.[1][13] Air pollution affects ground ozone, which experiences a biochemical change with sun light. The ground ozone damages plants. In the National Park Service, 30 plants species were damaged by the ground ozone and plants in higher elevation are prone to damage.[13]

Non-native species are another threat. For example, balsam woolly adelgids, an insect which was accidentally introduced from Europe kills Fraser fir. Many dead fir trees stand on mountain peaks.[13]

Fire

Wild fire is created by lightning on average twice per year, usually in May or June.[13] Although fire created by lightning is a natural disturbance and can be a threat, it is an important factor for ensuring biodiversity;[4][13] Some native species, such as table mountain pines and woodpeckers, benefit from the environmental changes after fire.[13]

In the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the National Park Service performs controlled burns: "to invigorate a species or ecosystem that benefits from fire" and "to reduce heavy accumulations of dead wood and brush which under drought conditions could produce catastrophic wildfires that threaten human life and valuable property."[13] While some rare plants thrive after a controlled fire, many others are destroyed.[13]

See also

Notes

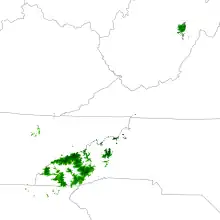

- ↑ Areas in green on the map exhibit high annual rainfall (at least 1400 mm), cool year-round temperatures (4 to 12°C average) wet summers (at least 10% of total precipitation occurring during the summer months), and moderate July temperatures (dark green less than 16°C, medium green less than 18°C, light green less than 20°C). While only the darkest green meets Alaback's original 1991 definition of a temperate rainforest,[7] the July temperature limits of this definition has since been broadened by a 2011 book by DellaSala, Alaback, and others.[4] Map created in ArcGIS Pro using open-access historical climate data at 30 arcsecond resolution.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Appalachian & Mixed Mesophytic Forests." WWF. WWF, n.d. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Leaf Gas Exchange of Understory Spruce–fir Saplings in Relict Cloud Forests, Southern Appalachian Mountains, USA." Reinhardt, Keith, and William K. Smith. Tree Physiology 28 (2007): 113-22. (Abstract).

- 1 2 David M. Gaffin; David G. Hotz (2000). "A Precipitation and Flood Climatology with Synoptic Features of Heavy Rainfall across the Southern Appalachian Mountains" (PDF). National Weather Digest. National Weather Digest. 24 (3): 3–15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 DellaSala, Dominick A. Temperate and Boreal Rainforests of the World: Ecology and Conservation. Washington, DC: Island, 2011. Print.

- 1 2 Tewksbury, C. E., and H. Van Miegroat. "Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics along a Climatic Gradient in a Southern Appalachian Spruce-fir Forest." National Research Council Canada 37 (2007): 1161-172. Web.

- 1 2 3 Creed, I. F., D. L. Morrison, and N. S. Nicholas. "., Is Coarse Woody Debris a Net Sink or Source of Nitrogen in the Red Spruce – Fraser Fir Forest of the Southern Appalachians, U.S.A.?" National Research Council Canada 24 (2004): 716-27. Print.

- 1 2 3 Alaback, P.B. (1991). "Comparative ecology of temperate rainforests of the Americas along analogous climatic gradients" (PDF). Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 64: 399–412.

- ↑ "Historical Climate Data". WorldClim. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ↑ "Weather". Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Drought in the Southern Appalachian temperate rainforest? Part 1." Coweeta Listening Project. N.p., 8 Oct. 2012. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

- ↑ David M. Gaffin (2012). Southern Appalachian Weather. New York: Vantage Press, 146 pages, ISBN 0-53316-528-8.

- 1 2 "Geologic Provinces of the United States: Appalachian Highlands Province." Archived 2013-03-11 at the Wayback Machine USGS Geology in the Parks. N.p., 13 Jan. 2004. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 "Great Smoky Mountains." National Park Service, n.d. Web. 29 Sept. 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Highlands Biological Station, Foundation, Nature Center, and Botanical Garden." Highlands Biological Station Foundation Nature Center and Botanical Garden RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

- ↑ "Paravitrea andrewsae High Mountain Supercoil". NatureServe Explorer. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ "Terrestrial Habitats of Virginia" (PDF). Conservation Gateway. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- 1 2 Stupka, Arthur. Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1964. Print.

- ↑ Bentley, Stanley L. Native Orchids of the Southern Appalachians. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000. Print.

- ↑ "Common Orchids in the Smokies". National Parks Service. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- 1 2 3 Harold W. Keller; Paul G. Davidson; Christopher H. Haufler; Damon B. Lesmeister (2003). "Polypodium appalachianum: An Unusual Tree Canopy Epiphyte in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park" (PDF). American Fern Journal. American Fern Society. 93 (1): 36–41.

- ↑ "Bazzania nudicaulis a liverwort". NatureServe Explorer. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- 1 2 "Cherokee History in the North Carolina Mountains and Beyond." Blue Ridge National Heritage Area. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Oct. 2013.

- ↑ "Pisgah & Its History". Pisgah Conservancy. Retrieved November 1, 2023.