| American eel | |

|---|---|

| |

_(4015394951).jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Anguilliformes |

| Family: | Anguillidae |

| Genus: | Anguilla |

| Species: | A. rostrata |

| Binomial name | |

| Anguilla rostrata Lesueur, 1821 | |

| |

| Range map | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Leptocephalus grassii | |

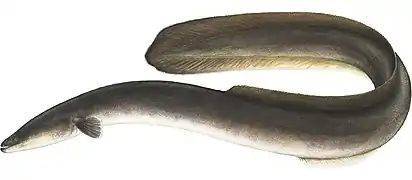

The American eel (Anguilla rostrata) is a facultative catadromous fish found on the eastern coast of North America. Freshwater eels are fish belonging to the elopomorph superorder, a group of phylogenetically ancient teleosts.[2] The American eel has a slender, supple, snake-like body that is covered with a mucus layer, which makes the eel appear to be naked and slimy despite the presence of minute scales. A long dorsal fin runs from the middle of the back and is continuous with a similar ventral fin. Pelvic fins are absent, and relatively small pectoral fins can be found near the midline, followed by the head and gill covers. Variations exist in coloration, from olive green, brown shading to greenish-yellow and light gray or white on the belly. Eels from clear water are often lighter than those from dark, tannic acid streams.[3]

The eel lives in fresh water and estuaries and only leaves these habitats to enter the Atlantic Ocean to make its spawning migration to the Sargasso Sea.[4] Spawning takes place far offshore, where the eggs hatch. The female can lay up to 4 million buoyant eggs and dies after egg-laying. After the eggs hatch and the early-stage larvae develop into leptocephali, the young eels move toward North America, where they metamorphose into glass eels and enter freshwater systems where they grow as yellow eels until they begin to mature.

The American eel is found along the Atlantic coast including the tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay, the Delaware River, and the Hudson River, and as far north as the Saint Lawrence River. It is also present in the river systems of the eastern Gulf of Mexico and in some areas further south. Like all anguillid eels, American eels hunt predominantly at night, and during the day they hide in mud, sand, or gravel very close to shore, at depths of roughly 5–6 feet (1.5–1.8 m). They feed on crustaceans, aquatic insects, small insects, and probably any aquatic organisms that they can find and eat.[5]

American eels are economically important in various areas along the East Coast as bait for fishing for sport fishes such as the striped bass, or as a food fish in some areas. Their recruitment stages, the glass eels, are also caught and sold for use in aquaculture, although this is now restricted in most areas.

Eels were once an abundant species in rivers, and were an important fishery for aboriginal people. The construction of hydroelectric dams has blocked their migrations and locally extirpated eels in many watersheds. For example, in Canada, the vast numbers of eels in the St. Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers have dwindled.[6]

Etymology

The American eel Anguilla rostrata was first described in 1817 by Lesueur. Anguilla is Latin for eel, and rostrata is a Latin word that can mean either "beaked or curved" or "long nose". French: Anguille d'Amérique, Spanish: Anguila americana.

Description

American eels can grow to 1.22 m (4.0 ft) in length and to 7.5 kg (17 lb) in weight. Females are generally larger than males, lighter in color, with smaller eyes and higher fins.[7] The body is elongate and snake-like. Its dorsal and anal fins are confluent with the rudimentary caudal fin. It lacks ventral fins but pectoral fins are present. The lateral line is well-developed and complete. The head is long and conical, with rather small, well-developed eyes. The mouth is terminal with jaws that are not particularly elongated. The teeth are small, pectinate or setiform in several series on the jaws and the vomer. Minute teeth also present on the pharyngeal bones, forming a patch on the upper pharyngeals. Tongue present with thick lips that are attached by a frenum in front. Nostrils are superior and well separated. Gill openings are partly below pectoral fins, relatively well-developed and well separated from one another. Inner gill slits are wide.[8]

The scales are small, rudimentary, cycloid, relatively well embedded below the epidermis and therefore often difficult to see without magnification.[9] The scales are not arranged in overlapping rows as they often are in other fish species but are rather irregular, in some places distributed like "parquet flooring". In general, one row of scales lies at right angle to the next, although the rows immediately above and below the lateral line lie at an angle of approximately 45°. Unlike other bony fishes, the first scales do not develop immediately after the larval stage but appear much later on.[10]

Several morphological features distinguish the American eel from other eel species. Tesch (1977)[11] described three morphological characteristics which persist through all stages from larvae to maturing eels: the total number of vertebrae (mean 107.2), the number of myomeres (mean 108.2), and the distance between the origin of the dorsal fin to the anus (mean 9.1% of total length).

Distribution and natural habitat

Geographic range

The distribution of the American eel encompasses all accessible freshwater (streams and lakes), estuaries and coastal marine waters across a latitudinal range of 5 to 62 N.[12] Their natural range includes the eastern North Atlantic Ocean coastline from Venezuela to Greenland and including Iceland.[13] Inland, this species extends into the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River[14] and its tributaries as far upstream as Minnesota and Wisconsin.[15]

Nonindigenous occurrences of this species in the United States were recorded from Lake Mead on the Colorado River and on the Arizona border.[16] It was stocked on a few occasions in Sacramento and San Francisco bay, California, in the late 1800s. No apparent evidence of survival on these occasions was noted.[17] It was also stocked and unintentionally introduced in various states, including Illinois, Indiana,[18] Nebraska, Nevada,[16] North Carolina,[19] Ohio and Pennsylvania.[20] Stockings of this species also occurred in Utah in the late 1800s, but soon disappeared.[20][21]

Natural habitat

Eels are bottom dwellers. They hide in burrows, tubes, snags, masses of plants, other types of shelters.[8] They are found in a variety of habitats including streams, rivers, and muddy or silt-bottomed lakes during their freshwater stage, as well as oceanic waters, coastal bays and estuaries.[6][13][14][22] Individuals during the continental stage occasionally migrate between fresh, salt and brackish water habitats and have varying degrees of residence time in each.[23][24][25] During winter, eels burrow under the mud and enter a state of torpor (or complete inactivity) at temperatures below 5 °C (41 °F).[26] although they may occasionally be active during this period.[6] Temperature requirements are suggested to be flexible. It has been found that American eels during elver stage can survive temperature as low as −0.8 °C (30.6 °F). Barila and Stauffer (1980) reported a final mean temperature preference at 16.7 °C (62.1 °F). Karlsson et al. (1984) disagreed with this interpretation and found the final temperature preference of 17.4 ± 2.0 °C with a 95% confidence interval.

Seasonal patterns described by Fletcher and Anderson (1972) generalize annual movements from freshwater to estuaries and coastal bays to feed during spring, then either a return during the fall to overwinter (juvenile and immature adults), or a southward migration to the spawning grounds (silver eels Continental phase eels appear highly plastic in habitat use. Eels are extremely mobile and may access habitats that appear unavailable to them, using small watercourses or moving through wet grasses. Small eels (<100 mm total length) are able to climb and may succeed in passing over vertical barriers.[27] Habitat availability may be reduced by factors such as habitat deterioration, barriers to upstream migration (larger eels), and barriers (i.e. turbines) to downstream migration that can result in mortality.[6]

Life cycle

The American eel's complex life history begins far offshore in the Sargasso Sea in a semelparous and panmictic reproduction.[28][29][30] In 1926 Marie Poland Fish described the collection of eggs that she observed hatch into eels,[31] which she expanded in her taxonomic description of the larval egg development.[32] From there, young eels drift with ocean currents and then migrate inland into streams, rivers and lakes. This journey may take many years to complete with some eels travelling as far as 6,000 kilometers. After reaching these freshwater bodies they feed and mature for approximately 10 to 25 years before migrating back to the Sargasso Sea in order to complete their life cycle.[6]

Life stages are detailed below.[33]

1. Eggs: The eggs hatch within a week of deposition in the Sargasso Sea. McCleave et al. (1987) suggested that hatching peaks in February and may continue until April. Wang and Tzeng (2000) proposed, on the basis of otolith back-calculations, that hatching occurs from March to October and peaks in August. However, Cieri and McCleave (2000) argued that these back-calculated spawning dates do not match collection evidence and may be explained by resorption. Fecundity for many eels is between about 0.5 to 4.0 million eggs, with larger individuals releasing as many as 8.5 million eggs.[34] The diameter of egg is about 1.1 mm. Fertilization is external, and adult eels are presumed to die after spawning. None has been reported to migrate up rivers.

2. Leptocephali: The leptocephalus is the larval form, a stage strikingly different from the adult form the eels will grow into. Leptocephali are transparent with a small pointed head and large teeth and are frequently described "leaf-like". The laterally compressed larvae are passively transported west and north to the coastal waters on the eastern coast of North America, by the surface currents of the Gulf Stream system, a journey that will last between 7 and 12 months.[11][29] Vertical distribution is usually restricted to the upper 350 m of the ocean. Growth has been evaluated at about 0.21 to 0.38 mm per day.

3. Glass eel: As they enter the continental shelf, leptocephali metamorphose into glass eels (juveniles), which are transparent and possess the typical elongate and serpentine eel shape. The term glass eel refers to all developmental stages between the end of metamorphosis and full pigmentation.[10] Metamorphosis occurs when leptocephali are about 55 to 65 mm long. Mean age at this metamorphosis has been evaluated at 200 days and estuarine arrival at 255 days; giving 55 days between glass eel metamorphosis and estuarine arrival. Young eels use selective tidal stream transport to move up estuaries. As they enter coastal waters, the animals essentially transform from a pelagic oceanic organism to a benthic continental organism.

4. Elvers: Glass eels become progressively pigmented as they approach the shore; these eels are termed elvers. The melanic pigmentation process occurs when the young eels are in coastal waters. At this phase of the life cycle, the eel is still sexually undifferentiated. The elver stage lasts about three to twelve months. Elvers that enter fresh water may spend much of this period migrating upstream. Elver influx is linked to increased temperature and reduced flow early in the migration season, and to tidal cycle influence later on.[11]

5. Yellow eels: This is the sexually immature adult stage of American eel. They begin to develop a yellow color and a creamy or yellowish belly. In this phase, the eels are still mainly nocturnal. Those remained in estuarine environment continue to go through their life cycle more quickly than those traveled into freshwater. Those in freshwater, however, tend to live longer and attain much larger sizes. Sexual differentiation occurs during the yellow stage and appears to be strongly influenced by environmental conditions. Krueger and Oliveira (1999) suggested that density was the primary environmental factor influencing the sex ratio of eels in a river, with high densities promoting the production of males. From life history traits of four rivers of Maine, Oliveira and McCleave (2000) evaluated that sexual differentiation was completed by 270 mm total length.

6. Silver eels: As the maturation process proceeds, the yellow eel metamorphoses into a silver eel. The silvering metamorphosis results in morphological and physiological modifications that prepare the animal to migrate back to the Sargasso Sea. The eel acquires a greyish colour with a whitish or cream coloration ventrally.[11][13] The digestive tract degenerates, the pectoral fins enlarge to improve swimming capacity, eye diameter expands and visual pigments in the retina adapt to the oceanic environment, the integument thickens,[11] percentage of somatic lipids increases to supply energy for migrating and spawning, gonadosomatic index and oocyte diameter increase, gonadotropin hormone (GTH-II) production increases, and osmoregulatory physiology changes.

Feeding

Eels are nocturnal and most of their feeding therefore occurs at night.[28] Having a keen sense of smell, eels most likely depend on scent to find food. The American eel is a generalist species which colonizes a wide range of habitats. Their diet is therefore extremely diverse and includes most of the aquatic animals sharing the same environment. The American eel feeds on a variety of things such as worms, small fish, clams and other mollusks, crustaceans such as soft-shelled crabs and a lot of macroinvertebrate insects. A study on gastric examination of eels revealed that "macroinvertebrates, predominantly of the Class Insecta, were eaten by 169 eels (99% of feeding eels)" and "the stonefly Acroneuria was the single most numerically dominant taxon observed in the diet, occurring in 67% of eel stomachs that contained food".[35]

Leptocephalus

Little is known about the food habits of leptocephali. Recent studies on other eel species (Otake et al. 1993; Mochioka and Iwamizu 1996) suggest that leptocephali do not feed on zooplankton but rather consume detrital particles such as marine snow and fecal pellets or particles such as discarded houses of larvacean tunicates.

Glass eel and elver

Based on laboratory experiments on European glass eels, Lecomte-Finiger (1983) reported that they were morphologically and physiologically unable to feed. However, Tesch (1977) found that elvers at a later stage of pigmentation, stage VIA4, were feeding.[11] Stomach examination of elvers caught during their upstream migration in the Petite Trinité River on the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence revealed that elvers fed primarily on insect larvae.

Yellow eel

The yellow eel is essentially a nocturnal benthic omnivore. Prey includes fishes, molluscs, bivalves, crustaceans, insect larvae, surface-dwelling insects, worms, frogs and plants. The eel prefers small prey animals which can easily be attacked.[11] Food type varies with body size.[11] Stomachs of eels less than 40 cm and captured in streams contained mainly aquatic insect larvae, whereas larger eels fed predominantly on fishes and crayfishes. Insect abundance decreased in larger eels. The eel diet adapts to seasonal changes and the immediate environment. Feeding activity decreases or stops during the winter, and food intake ceases as eels physiologically prepare for the spawning migration.[34]

Predation

Little information about predation on eels has been published. It was reported that elvers and small yellow eels are prey of largemouth bass and striped bass, although they were not a major parts of these predators' diet.[36] Leptocephali, glass eels, elvers, and small yellow eels are likely to be eaten by various predatory fishes. Older eels are also known to eat incoming glass eels.[37] They also fall prey to other species of eels, bald eagles, gulls, as well as other fish-eating birds.[38] American eels also make up the entirety of the diet of adult rainbow snakes, lending the species one of their common names; eel moccasin.[39]

Commercial fisheries

The major outlet for US landings of yellow and silver eels is the EU market.[8]

In the 1970s, the annual North Atlantic harvest averaged 125,418 kg, with an average value of $84,000. In 1977, the eel landings from Maine, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts were about 79,700, 2,700, and 143,300 kg, valued at $263,000, $5,000, and $170,000, respectively (US Department of Commerce 1984)

During the 1980s and early 1990s, the American eel was one of the top three species in commercial value to Ontario's fishing industry. At its peak, the eel harvest was valued at $600,000 and, in some years, eel accounted for almost half of the value of the entire commercial fish harvest from Lake Ontario. The commercial catch of American eel has declined from approximately 223,000 kilograms (kg) in the early 1980s to 11,000 kg in 2002.[41]

Conservation

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the American eel is at very high risk of extinction in the wild.[42][1]

Substantial decline in numbers and fishery landings of American eels over their range in eastern Canada and the US was noted, raising concerns over the status of this species. The number of juvenile eels in the Lake Ontario area decreased from 935,000 in 1985 to about 8,000 in 1993 and was approaching zero levels in 2001. Rapid declines were also recorded in Virginia, as well as in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island in Canada.

Because of its complex life cycle, the species face a broad range of threats, some of which are specific to certain growth stage. Being catadromous, the eels' reproductivity success depends heavily on free downstream passage for spawning migration. It also depends on the availability of diverse habitats for growth and maturation.

Sex ratio in the population can also be affected because males and females tend to utilize different habitats. Impacts on certain regions may greatly impact the number of either sex.

Despite being able to live in a wide range of temperatures and different levels of salinity, American eels are very sensitive to low dissolved oxygen level,[43] which is typically found below dams. Contaminations of heavy metals, dioxins, chlordane, and polychlorinated biphenyls as well as pollutants from nonpoint source can bioaccumulate within the fat tissues of the eels, causing dangerous toxicity and reduced productivity.[44] This problem is exacerbated due to the high fat content of eels.

Construction of dams and other irrigation facilities seriously decreases habitat availability and diversity for the eels. Dredging can affect migration, population distribution and prey availability. Overfishing or excessive harvesting of juveniles can also negatively impact local populations.

Other natural threats come from interspecific competition with exotic species like the flathead catfish (Pylodictis olivaris) and blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus), pathogens and parasites, and changes in oceanographic conditions that can alter currents—this potentially changes larval transport and migration of juveniles back to freshwater streams.

Conservation measures

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reviewed the status of the American eel both in 2007 and in 2015, finding both times that Endangered Species Act protection for the American eel is not warranted.[45]

The Canadian province of Ontario has cancelled the commercial fishing quota since 2004. Eel sport fishery has been closed. Efforts have been made to improve the passage in which eels migrate across the hydroelectric dams on St. Lawrence River.[46]

As of August 2023, A. rostrata is under consideration for protection under the Canadian Species at Risk Act.[47] The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada reported that the species was threatened in 2012.[48]

Sustainable consumption

In 2010, Greenpeace International has added the American eel to its seafood red list. "The Greenpeace International seafood red list is a list of fish that are commonly sold in supermarkets around the world, and which have a very high risk of being sourced from unsustainable fisheries."[49]

References

- 1 2 Jacoby, D.; Casselman, J.; DeLucia, M.-B.; Gollock, M. (2017). "Anguilla rostrata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T191108A121739077. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T191108A121739077.en. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ↑ Nelson JS (1994) Fishes of the world. John Wiley and Sons, New York

- ↑ McCord, John W. American Eel. South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

- ↑ Nuwer, Rachel (December 7, 2015) Closing In on Where Eels Go to Connect. New York Times

- ↑ NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory

- 1 2 3 4 5 American Eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report 2006. ISBN 0-662-43225-8

- ↑ Smit, D.G. Order ANGUILLIFORMES. National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., USA

- 1 2 3 Fahay, Michael P. (August 1978) Biological and Fisheries Data on. American eel, Anguilla rostrata (Lesueur). Sandy Hook Laboratory. US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- ↑ Hardy, J.D., Jr. (1978) Development of Fishes of the Mid-Atlantic Bight: An Atlas of Egg, Larval, and Juvenile Stages. Volume II – Anguillidae thorough Syngnathidae. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

- 1 2 Tesch F.W. (2003). The eel. Third Edition. Blackwell Science. ISBN 0632063890

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tesch, F.W. (1977). The eel: biology and management of anguillid eels. Chapman and Hall, London

- ↑ Bertin, L. (1956). Eels: a biological study. Cleaver-Hume Press Ltd., London.

- 1 2 3 Scott, W.B. and E.J. Crossman. (1973) Freshwater fishes of Canada. Bulletin 184, Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Ottawa. The Bryant Press Limited, Ottawa, ON.

- 1 2 Jessop, B.M. (2006) Underwater world: American Eel. Communications Directorate, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa, ON.

- ↑ Cochran, Philip (2006). "Historical Notes on American Eels (Anguilla rostrata) in the Upper Midwest" (PDF). North American Native Fishes Association.

- 1 2 Minckley, W. L. (1973). Fishes of Arizona. Arizona Fish and Game Department. Sims Printing Company, Inc., Phoenix, AZ.

- ↑ Smith, H. M. (1896). "A review of the history and results of the attempts to acclimatize fish and other water animals in the Pacific states", pp. 379–472 in Bulletin of the U.S. Fish Commission, Vol. XV, for 1895.

- ↑ Gerking, S. D. (1945). "Distribution of the fishes of Indiana". Investigations of Indiana Lakes and Streams. 3: 1–137.

- ↑ Shute, P.W. and D.A. Etnier. (2000). Southeastern fishes council regional reports – 2000. Region III – North-Central.

- 1 2 Sigler, F. F., and R. R. Miller. (1963). Fishes of Utah. Utah Department of Fish and Game, Salt Lake City, UT.

- ↑ Fuller, Pam and Nico, Leo (2012) Anguilla rostrata. USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL.

- ↑ Scott, W.B and Scott, M.G. (1988) "Atlantic fishes of Canada". Canadian Bulletin of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 219.

- ↑ Fletcher, G.L. and T. Anderson. (March 1972). "A preliminary survey of the distribution of the American Eel (Anguilla rostrata) in Newfoundland". MSRL Technical Report No. 7. Marine Sciences Research Laboratory, St. John's, NL.

- ↑ Clarke, K.D., R.J. Gibson and D.A. Scruton. (January 2007). "A review of the habitat associations and distribution of the American Eel within Newfoundland and Labrador". Presentation at the Canadian Conference for Fisheries Research.

- ↑ Jonsson, B.; Jessop, B. M. (2010). "Geographic effects on American eel (Anguilla rostrata) life history characteristics and strategies". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 67 (2): 326–346. doi:10.1139/F09-189.

- ↑ Walsh, P.J.; Foster, G.D.; Moon, T.W. (1983). "The effects of temperature on metabolism of the American Eel Anguilla rostrata (LeSueur): compensation in the summer and torpor in the winter". Physiological Zoology. 56 (4): 532–540. doi:10.1086/physzool.56.4.30155876. JSTOR 30155876. S2CID 87523062.

- ↑ Legault, A (1988). "Le franchissement des barrages par l'escalade de l'anguille: étude en Sèvre Niortaise" (PDF). Bulletin Français de la Pêche et de la Pisciculture. 308 (308): 1–10. doi:10.1051/kmae:1988010.

- 1 2 Helfman, G.S., D.E. Facey, L.S. Hales, Jr., and E.L Bozeman, Jr. (1987). "Reproductive ecology of the American Eel". pp. 42–56 in M.J. Dadswell, R.L. Klauda, C.M. Moffitt, R.L. Saunders, R.A. Rulifson, and J.E. Cooper (eds.) Common strategies of anadromous and catadromous fishes. American Fisheries Society Symposium 1, Maryland.

- 1 2 Schmidt, J. (1922). "The breeding places of the eel". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 211 (382–390): 179–208. doi:10.1098/rstb.1923.0004. JSTOR 92087.

- ↑ Wirth, T; Bernatchez, L (2003). "Decline of North Atlantic eels: A fatal synergy?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 270 (1516): 681–8. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2301. PMC 1691294. PMID 12713741.

- ↑ Fish, Marie Poland (1926). "Preliminary Note on the Egg and Larva of the American Eel (Anguilla rostrata)". Science. 64 (1662): 455–456. Bibcode:1926Sci....64..455P. doi:10.1126/science.64.1662.455. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 1651252. PMID 17741951.

- ↑ Fish, Marie Poland (1927). "Contributions to the Embryology of the American Eel (Anguilla rostrata Lesueur)". Zoologica. 8 (5): 289–324.

- ↑ Species Spotlight: American eel (Anguilla rostrata). American Littoral Society

- 1 2 Wenner, C. A.; Musick, J. A. (1975). "Food Habits and Seasonal Abundance of the American eel, Anguilla rostrata, from the Lower Chesapeake Bay". Chesapeake Science. 16 (1): 62–66. doi:10.2307/1351085. JSTOR 1351085.

- ↑ Denoncourt, Charles E. (1993). ""Feeding selectivity of the American eel Anguilla rostrata (LeSueur) in the upper Delaware River."". American Midland Naturalist. 129 (2): 301–308. doi:10.2307/2426511. JSTOR 2426511.

- ↑ Hornberger, M. L., J. S. Tuten, A. Eversole, J. Crane, R. Hansen, and M. Hinton. (1978) "Anierican eel investigations". Completion report for March 1977 – July 1978. South Carolina Wi1dlife and Marine Research Department, Charleston, and Clemson University, Clemson.

- ↑ Sorensen, P. W.; Bianchini, M. L. (1986). "Environmental Correlates of the Freshwater Migration of Elvers of the American Eel in a Rhode Island Brook". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 115 (2): 258–268. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1986)115<258:ECOTFM>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Sinha, V. R. P.; Jones, J. W. (2009). "On the food of the freshwater eels and their feeding relationship with the salmonids". Journal of Zoology. 153: 119–137. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1967.tb05034.x.

- ↑ Rainbow Snake Chesapeake Bay Program

- ↑ Based on data sourced from the FishStat database, FAO.

- ↑ American Eel in Ontario. mnr.gov.on.ca

- ↑ "American Eel Is in Danger of Extinction". Scientific American. December 1, 2014.

- ↑ Hill, L. J. (1969). "Reactions of the American eel to dissolved oxygen tensions". Tex. J. Sci. 20: 305–313.

- ↑ Hodson, P. V.; Castonguay, M.; Couillard, C. M.; Desjardins, C.; Pelletier, E.; McLeod, R. (1994). "Spatial and Temporal Variations in Chemical Contamination of American Eels, Anguilla rostrata, Captured in the Estuary of the St, Lawrence River". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 51 (2): 464–478. doi:10.1139/f94-049.

- ↑ "The American Eel". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

- ↑ Protecting the Vanishing American Eel. mnr.gov.on.ca

- ↑ "American Eel (Anguilla rostrata)". Species at risk public registry. Government of Canada. June 13, 2023. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ↑ COSEWIC (2012). "COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American Eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada". Ottawa: Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Retrieved August 6, 2023.

- ↑ Greenpeace International Seafood Red list Archived August 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. greenpeace.org

External links

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2005). "Anguilla rostrata" in FishBase. 10 2005 version.

- ESA protection