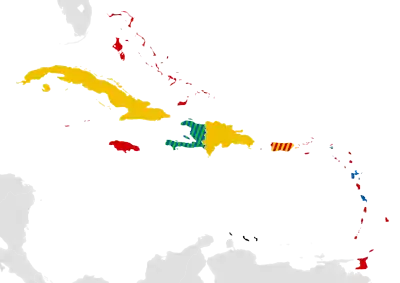

The languages of the Caribbean reflect the region's diverse history and culture. There are six official languages spoken in the Caribbean:

- Spanish (official language of Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Bay Islands (Honduras), Corn Islands (Nicaragua), Isla Cozumel, Isla Mujeres (Mexico), Nueva Esparta (Venezuela) the Federal Dependencies of Venezuela and San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina (Colombia))

- French (official language of Guadeloupe, Haiti, Martinique, Saint Barthélemy, French Guiana and Saint-Martin)

- English (official language of Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, Puerto Rico (which, despite belongs to but is not part of the United States, as an American territory, has an insubstantial anglophone contingent), Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Sint Maarten, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina (Colombia), Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos Islands, and U.S. Virgin Islands)[1]

- Dutch (official language of Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, Saba, Sint Eustatius, Sint Maarten, and Suriname)

- Haitian Creole (official language of Haiti)

- Papiamento (a Portuguese and Spanish-based Creole language) (official language of Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao)

There are also a number of creoles and local patois. Dozens of the creole languages of the Caribbean are widely used informally among the general population. There are also a few additional smaller indigenous languages. Many of the indigenous languages have become extinct or are dying out.

At odds with the ever-growing desire for a single Caribbean community,[2] the linguistic diversity of a few Caribbean islands has made language policy an issue in the post-colonial era. In recent years, Caribbean islands have become aware of a linguistic inheritance of sorts. However, language policies being developed nowadays are mostly aimed at multilingualism.

Languages

Most languages spoken in the Caribbean are either European languages (namely Spanish, English, French, and Dutch) or European language-based creoles.

Spanish-speakers are the most numerous in the Caribbean by far, with over 25 million native speakers in the Greater Antilles . English is the first or second language in most of the smaller Caribbean islands and is also the unofficial "language of tourism", the dominant industry in the Caribbean region. In the Caribbean, the official language is usually determined by whichever colonial power (England, Spain, France, or the Netherlands) held sway over the island first or longest.

English

The first permanent English colonies were founded at Saint Kitts (1624) and Barbados (1627). The English language is the third most established throughout the Caribbean; however, due to the relatively small populations of the English-speaking territories, only 14%[3] of West Indians are English speakers. English is the official language of about 18 Caribbean territories inhabited by about 6 million people, though most inhabitants of these islands may more properly be described as speaking English creoles rather than local varieties of standard English.

Spanish

Spanish was introduced to the Caribbean with the voyages of discovery by Christopher Columbus in 1492. The Caribbean English-speakers are vastly outnumbered by Spanish speakers by a ratio of about four to one due to the high densities of populations on the larger, Spanish-speaking, islands; some 64% of West Indians speak Spanish. The countries that are included in this group are Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and some islands off Central America (Cozumel, Isla Mujeres, San Andrés and Providencia, Corn Islands, The Bay Islands) and South America (Federal Dependencies of Venezuela and Nueva Esparta).

French

About one-quarter of West Indians speak French or a French-based creole. They live primarily in Guadeloupe and Martinique, both of which are overseas departments of France; Saint Barthélemy and the French portion of Saint Martin, both of which are overseas collectivities of France; the independent nation of Haiti (where both French and Haitian Creole are official languages);[4][5] and the independent nations of Dominica and Saint Lucia, which are both officially English-speaking but where the French-based Antillean Creole is widely used, especially Saint Lucian Creole which is related to Haitian Creole and French to a lesser degree.

Dutch

Dutch is an official language of the Caribbean islands that remain under Dutch sovereignty. However, Dutch is not the dominant language on these islands. On the islands of Aruba, Curaçao and Bonaire, a creole based on Portuguese, Spanish and West African languages known as Papiamento is predominant, while in Sint Maarten, Saba and Sint Eustatius, English, as well as a local English creole, are spoken. A Dutch creole known as Negerhollands was spoken in the former Danish West Indian islands of Saint Thomas and Saint John, but is now extinct. Its last native speaker died in 1987.[6]

Other languages

Caribbean Hindustani

Caribbean Hindustani is a form of the Bhojpuri and Awadhi dialect of Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu) spoken by descendants of the indentured laborers from India in Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, and other parts of the Caribbean.[7]

Indigenous languages

Several languages spoken in the Caribbean belong to language groups concentrated or originating in the mainland countries bordering on the Caribbean: Suriname, Guyana, French Guiana, Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, and Peru.

Many indigenous languages (actually spoken with the mainland Caribbean rather than the islands) have been added to the list of endangered or extinct languages—for example, Arawak languages (Shebayo, Igñeri, Lokono, Garifuna of St. Vincent, and the one now labeled Taíno by scholars, once spoken in the Greater Antilles), Caribbean (Nepuyo and Yao), Taruma, Atorada, Warrau, Arecuna, Akawaio and Patamona. Some of these languages are still spoken there by a few people.[8][9]

Creole languages

Creoles are contact languages usually spoken in rather isolated colonies, the vocabulary of which is mainly taken from a European language (the lexifier).[10] Creoles generally have no initial or final consonant clusters but have a simple syllable structure which consists of alternating consonants and vowels (e.g. "CVCV").[11]

A substantial proportion of the world's creole languages are to be found in the Caribbean and Africa, due partly to their multilingualism and their colonial past. The lexifiers of most of the Caribbean creoles and patois are languages of Indo-European colonizers of the era. Creole languages continue to evolve in the direction of European colonial languages to which they are related, so that decreolization occurs and a post-creole continuum arises. For example, the Jamaican sociolinguistic situation has often been described in terms of this continuum.[12] Papiamento, spoken on the so-called 'ABC' islands (Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao), shows traces of both indigenous languages and Spanish,[13] Portuguese, and Dutch lexicons.).

In Jamaica, though generally an English-speaking island, a patois drawing on a multitude of influences including Spanish, Portuguese, Hindi, Arawak, Irish and African languages is widely spoken. In Barbados, a dialect often known as "bajan" have influences from West African languages that can be heard on a regular daily basis.

In Haiti, a French-speaking island that also mixed between the French and West African languages to be based on Haitian Creole after the slaves won independence from France on 1 January 1804 that was once mixed between the white French settlers and African slaves that was imported from Africa to the New World. Haiti became the first Latin American country to gain independence and became the first black republic, the first Caribbean nation and the second independent nation in the Americas after the United States under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines.

Contact between the French and English-lexified creoles is fairly common in the Lesser Antilles (apart from Saint Lucia), and can also be observed on Dominica, Saint Vincent, Carriacou, Petite Martinique and Grenada.[14]

In Martinique, which is now part of the French Republic, became part of the French Caribbean, the French are bound for the African coast where many captives were taken to the French colony of Martinique which began in 1635 after the discovery of Christopher Columbus in 1502. Code Noir was published by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the French statesman and minister of the Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique where Martinique was colonized by the France during the reign of King Louis XIV, the Sun King. During the French colonization, many slaves are imported from Africa and sold in the Americas, the French founded the port city of Fort-Royal (now Fort-de-France) in 1638 as it was titled The Paris of the Caribbean or the French Pearl in the Caribbean. Martinique was changed six times between the masters of Britain and France during the Seven Years' War, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars until Napoleon was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo during the War of the Seventh Coalition where he was exiled and died in Saint Helena at the age of 51 on 5 May 1821. Slavery was finally abolished on 27 April 1848 in the French Caribbean which marks the end of a long painful harsh chapter of the Slave eras. Martinique commemorates emancipation with a national holiday on 22 May that declared as the Abolition Day. In 1851, Martinique was seeking to replace former African slave laborers who had abandoned plantation work on being given their liberty, recruited several thousand laborers from the Indian French colonial settlement of Pondichéry. They are primarily most concentrated in the northern Tamil communes of Martinique, where the main plantations are located. A majority of the Indian community hails from Pondichéry and these immigrants brought them with their Hindu religion. Many Hindu temples are still in use in Martinique. French was the official language that was once used by the settlers and Martinican Creole that was also used by the African slaves are developed.

In Saint Lucia, it was colonised by France as part of the French Caribbean, followed by the British that became part of the British Caribbean, the official language of Saint Lucia was English while Saint Lucian Creole French was also spoken, but was and still is related to Haitian Creole once the French had captured the slaves from Africa and sold in the Americas. Saint Lucian Creole emerged as a form of communication between the African slaves and the French colonizers. It was each ruled seven times and at war which was 14 times between England and France after the Seven Years' War as well as the Battle of St. Lucia during the American Revolutionary War in 1778. While the French Revolution broke out in Paris in 1789, a revolutionary tribunal was sent to Saint Lucia, headed by Captain La Crosse. Following the declaration of the French Republic on 22 September 1792 and the Execution of Louis XVI on 21 January 1793, Britain declared war on France in the Caribbean until the French National Convention abolished slavery on 4 February 1794. The Haitian Revolution led by the former slaves including Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henri Christophe while the other Haitian leader Toussaint Louverture was captured by the French in 1802 and died in France on 7 April 1803. The Battle of Vertières led by the former slaves including Dessalines defeated the French and declared the colony of Saint-Domingue independence on 1 January 1804 and renamed the country Ayiti meaning (Land of Mountains). Haiti became the world's first and oldest free black nation in the modern world, and the second oldest independent country in the Americas after the United States. Saint Lucia gained independence from the United Kingdom on 22 February 1979, as the United States recognized Saint Lucia as a federated state of the British Commonwealth.

Others

Asian languages such as Chinese and other Indian languages such as Tamil are spoken by Asian expatriates and their descendants exclusively. In earlier historical times, other Indo-European languages, such as Danish or German,[15] could be found in northeastern parts of the Caribbean.

Change and policy

Throughout the long multilingual history of the Caribbean continent, Caribbean languages have been subject to phenomena like language contact, language expansion, language shift, and language death.[16] Two examples are the Spanish expansion, in which Spanish-speaking peoples expanded over most of central Caribbean, thereby displacing Arawak speaking peoples in much of the Caribbean, and the Creole expansion, in which Creole-speaking peoples expanded over several of islands. Another example is the English expansion in the 17th century, which led to the extension of English to much of the north and the east Caribbean.

Trade languages are another age-old phenomenon in the Caribbean linguistic landscape. Cultural and linguistic innovations that spread along trade routes, and languages of peoples dominant in trade, developed into languages of wider communication (linguae francae). Of particular importance in this respect are French (in the central and east Caribbean) and Dutch (in the south and the east Caribbean).

After gaining independence, many Caribbean countries, in the search for national unity, selected one language (generally the former colonial language) to be used in government and education. In recent years, Caribbean countries have become increasingly convinced of the importance of linguistic diversity. Language policies that are being developed nowadays are mostly aimed at multilingualism.[17]

Demographics

Of the 38 million West Indians (as of 2001),[18] about 62% speak Spanish (a west Caribbean lingua franca). About 25% speak French, about 15% speak English, and 5% speak Dutch. Spanish and English are important second languages: 24 million and 9 million speak them as second languages.

The following is a list of major Caribbean languages (by total number of speakers)[needs updating]:

| Country/Territory | Population | Official language | Spoken languages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anguilla | 11,430 | English | English, Anguillian Creole English, Spanish (immigrants) |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 66,970 | English | English, Antiguan Creole English, Spanish |

| Aruba | 103,400 | Dutch, Papiamento | Papiamento, Dutch, English, Spanish |

| The Bahamas | 303,611 | English | English, Bahamian Creole, Haitian Creole (immigrants), Spanish, Chinese (immigrants) |

| Barbados | 275,330 | English | English, Bajan Creole, Spanish |

| Bay Islands, Honduras | 49,151 | Spanish | Spanish, English, Creole English, Garifuna |

| Bermuda | 63,503 | English | English, Bermudian Vernacular English, Portuguese |

| Bonaire | 14,230 | Dutch | Papiamento, Dutch, English, Spanish |

| Bocas del Toro Archipelago | 13,000 | Spanish | Spanish |

| British Virgin Islands | 20,812 | English | English, Virgin Islands Creole English, Spanish (immigrants) |

| Cayman Islands | 40,900 | English | English, Cayman Creole English, Spanish (immigrants) |

| Corn Islands | 7,429 | Spanish | Spanish, English |

| Cuba | 11,217,100 | Spanish | Spanish |

| Curaçao | 130,000 | Dutch, Papiamentu, English | Papiamento, Dutch, English, Spanish |

| Dominica | 70,786 | English | English, Antillean Creole French, French, Haitian Creole (immigrants), Spanish (immigrants) |

| Federal Dependencies of Venezuela | 2,155 | Spanish | |

| Dominican Republic | 8,581,477 | Spanish | Spanish, Haitian Creole (immigrants), English (immigrants) |

| Grenada | 89,227 | English | English, Grenadian Creole English, Antillean Creole French, Spanish, Andaluz |

| Guadeloupe | 431,170 | French | French, Antillean Creole French, Spanish (immigrants) |

| Guyana | 747,884 | English | English, Guyanese Creole, Guyanese Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu), Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, Tamil, and the native languages: Akawaio, Macushi, Waiwai, Arawak, Patamona, Warrau, Carib, Wapishana, and Arekuna |

| Haiti | 6,964,549 | French, Creole | French, Haitian Creole |

| Isla Cozumel | 50,000 | Spanish | Spanish, English |

| Isla Mujeres | 12,642 | Spanish | Spanish, English |

| Jamaica | 2,665,636 | English | English, Jamaican Patois, Spanish, Caribbean Hindustani, Irish, Chinese, Portuguese, Arabic |

| Martinique | 418,454 | French | French, Antillean Creole French, Spanish (immigrants) |

| Montserrat | 7,574 | English | English, Montserrat Creole English |

| Nueva Esparta | 491,610 | Spanish | |

| Puerto Rico | 3,808,610 | Spanish, English | Spanish, English |

| Saba | 1,704 | Dutch | English, Saban Creole English, Dutch |

| Saint Barthelemy | 6,500 | French | French, French Creole, English |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 38,756 | English | English, Saint Kitts and Nevis Creole English, Spanish |

| Saint Lucia | 158,178 | English | English, Saint Lucian Creole French, French , Spanish |

| Saint Martin | 27,000 | French | English, St. Martin Creole English, French, Antillean Creole French (immigrants), Spanish (immigrants), Haitian Creole (immigrants) |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 115,942 | English | English, Vincentian Creole English, Antillean Creole French, Spanish |

| San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina | 75,167 | Spanish | English, Spanish, San Andrés–Providencia Creole |

| Sint Eustatius | 2,249 | Dutch | English, Statian Creole English, Dutch, Spanish (immigrants) |

| Sint Maarten | 41,718 | Dutch, English | English, St. Martin Creole English, Dutch, Papiamento (immigrants), Antillean Creole French (immigrants), Spanish (immigrants), Haitian Creole (immigrants) |

| Suriname | 541,638 | Dutch | Dutch, Sranan Tongo, Sarnami Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu), Javanese, Ndyuka, Saramaccan, Chinese, English, Portuguese, French, Spanish, and the native languages: Akurio, Arawak-Lokono, Carib-Kari'nja, Mawayana, Sikiana-Kashuyana, Tiro-Tiriyó, Waiwai, Warao, and Wayana |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1,169,682 | English | English, Trinidadian Creole, Tobagonian Creole, Trinidadian Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu), Spanish, Chinese, Arabic, Trinidadian French Creole, Yoruba |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | 36,132 | English | English, Turks and Caicos Creole English, Spanish , Haitian Creole (immigrants) |

| United States Virgin Islands | 108,000 | English | English, Virgin Islands Creole English, Danish (colonial), Spanish (immigrants), Antillean Creole French (immigrants) |

Linguistic features

Some linguistic features are particularly common among languages spoken in the Caribbean, whereas others seem less common. Such shared traits probably are not due to a common origin of all Caribbean languages. Instead, some may be due to language contact (resulting in borrowing) and specific idioms and phrases may be due to a similar cultural background.

Syntax

Widespread syntactical structures include the common use of adjectival verbs for e.g.:" He dirty the floor. The use of juxtaposition to show possession as in English Creole, "John book" instead of Standard English, "John's book", the omission of the copula in structures such as "he sick" and "the boy reading". In Standard English, these examples would be rendered, 'he seems/appears/is sick' and "the boy is reading".

Semantic

Quite often, only one term is used for both animal and meat; the word nama or nyama for animal/meat is particularly widespread in otherwise widely divergent Caribbean languages.

See also

- Anglophone Caribbean

- Antillean Creole

- Caribbean English

- Caribbean Spanish

- Caribbean Hindustani

- Creole language

- Use of the Dutch language in the Caribbean

- English-based creole languages

- French-based creole languages

- List of sovereign states and dependent territories in the Caribbean

- Pre-Arawakan languages of the Greater Antilles

Notes

- ↑ https://www.vinow.com/general_usvi/culture/virgin-islands-language/

- ↑ For Caribbean community see Commonwealth Caribbean and CARICOM

- ↑ Using the 2001 census of the region.

- ↑ Orjala, Paul Richard. (1970). A Dialect Survey Of Haitian Creole, Hartford Seminary Foundation. 226p.

- ↑ Pompilus, Pradel. (1961). La langue française en Haïti. Paris: IHEAL. 278p

- ↑ Ureland, P. Sture. (1985). 'Entstehung von Sprachen und Völkern'(Origins of Languages and Peoples). Tübingen

- ↑ "Sarnámi Hindustani". Omniglot. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ↑ Amerindian Peoples’ Association.(2003). Guyana

- ↑ Devonish, H., (Mar 2010) 'The Language Heritage of the Caribbean' Barbados: University of the West Indies

- ↑ Lexifiers are languages of the former major colonial powers, whereas the grammatical structure is usually attributed to other languages spoken in the colonies, the so-called substrates.

- ↑ Romaine, Suzanne (1988): Pidgin and creole languages. London: Longman, p.63

- ↑ David, DeCamp. (1971) Pidgin and Creole Languages Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 13-39:351

- ↑ see newspaper Civilisadó 1871–1875

- ↑ Loftman, Beryl I. (1953). Creole Languages Of The Caribbean Area, New York: Columbia University

- ↑ Schumann, Theophilus. (1748). Letters from Pilgerhut in Berbice to Ludwig von Zinzendorf, Berlin. A pilgrim who, with help from a native Arawak, translated his German Bible into the native language.

- ↑ Devonish, H. (2004). Languages disappeared in the Caribbean region, University of the West Indies

- ↑ Taylor, Douglas. (1977). Languages of the West Indies, London: Johns Hopkins University Press

- ↑ All population data is from The World Factbook estimates (July 2001) with these exceptions: Bay Islands, Cancun, Isla Cozumel, Isla de Margarita, Saint Barthelemy, Saint Martin (these were obtained by CaribSeek's own research. Anguilla, Bahamas, Cuba, Cayman Islands, and the Netherlands Antilles population data are from the sources mentioned below, and are estimates for the year 2000.

References

- Adelaar, Willem F. H. (2004). Languages of the Andes: The Arawakan languages of the Caribbean, Cambridge University Press ISBN 052136275X

- Appel, René., Muysken, Pieter. (2006). Language Contact and Bilingualism: Languages of the Caribbean

- Ferreira, Jas. (). Caribbean Languages and Caribbean Linguistics

- Gramley, Stephan., Pätzold, Kurt-Michael. (2003). A survey of modern English: The Languages of the Caribbean.

- Patterson, Thomas C., Early colonial encounters and identities in the Caribbean

- Penny, Ralph John, (2002). A history of the Spanish language.

- Roberts, Peter. (1988). West Indians & their language Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sprauve, Gilbert A., (1990). Dutch Creole/English Creole distancing: historical and contemporary data considered, International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Vol 1990:85, pp. 41–50

- Taylor, Douglas M., (1977) Languages of the West Indies, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

.svg.png.webp)