|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Anatomical terminology |

|---|

An anatomical plane is a hypothetical plane used to transect the body, in order to describe the location of structures or the direction of movements. In human and non-human anatomy, three principal planes are used:

- The sagittal plane or lateral plane (longitudinal, anteroposterior) is a plane parallel to the sagittal suture. It divides the body into left and right.

- The coronal plane or frontal plane (vertical) divides the body into dorsal and ventral (back and front, or posterior and anterior) portions.

- The transverse plane or axial plane (horizontal) divides the body into cranial and caudal (head and tail) portions.

Terminology

There could be any number of sagittal planes, but only one cardinal sagittal plane exists. The term cardinal refers to the one plane that divides the body into equal segments, with exactly one half of the body on either side of the cardinal plane. The term cardinal plane appears in some texts as the principal plane. The terms are interchangeable.[1]

Human anatomy

In human anatomy, the anatomical planes are defined in reference to a body in the upright or standing orientation.

- A transverse plane (also known as axial or horizontal plane) is parallel to the ground; it separates the superior from the inferior, or the head from the feet. The transverse planes identified in Terminologia Anatomica are the transpyloric plane, the subcostal plane, the transumbilical (or umbilical) plane, the supracristal plane, the intertubercular plane, and the interspinous plane.

- A coronal plane (also known as frontal plane) is perpendicular to the ground; it separates the anterior from the posterior, the front from the back, and the ventral from the dorsal.

- A sagittal plane (also known as anteroposterior plane) is perpendicular to the ground, separating left from right. The median (or midsagittal) plane is the sagittal plane in the middle of the body; it passes through midline structures such as the navel and the spine. All other sagittal planes (also known as parasagittal planes) are parallel to it.

The axes and sagittal plane are the same for bipeds and quadrupeds, but the orientations of the coronal and transverse planes switch. The axes on particular pieces of equipment may or may not correspond to the axes of the body, especially since the body and the equipment may be in different relative orientations.

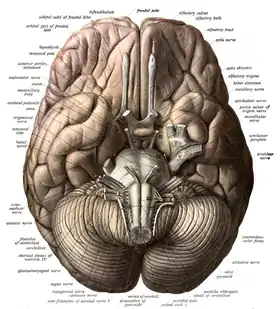

Brain viewed from below. This is an example of a transverse plane.

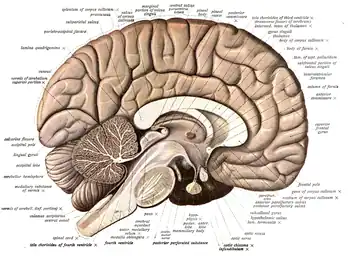

Brain viewed from below. This is an example of a transverse plane. Brain cut in half through the midsection. This is an example of a sagittal plane.

Brain cut in half through the midsection. This is an example of a sagittal plane.

Uses

Motion

When describing anatomical motion, these planes describe the axis along which an action is performed. So by moving through the transverse plane, movement travels from head to toe. For example, if a person jumped directly up and then down, their body would be moving through the transverse plane in the coronal and sagittal planes.

A longitudinal plane is any plane perpendicular to the transverse plane. The coronal plane and the sagittal plane are examples of longitudinal planes.

Medical imaging

Sometimes the orientation of certain planes needs to be distinguished, for instance in medical imaging techniques such as sonography, CT scans, MRI scans, or PET scans. There are a variety of different standardized coordinate systems. For the DICOM format, the one imagines a human in the anatomical position, and an X-Y-Z coordinate system with the x-axis going from front to back, the y-axis going from right to left, and the z-axis going from toe to head. The right-hand rule applies. [2]

Finding anatomical landmarks

In humans, reference may take origin from superficial anatomy, made to anatomical landmarks that are on the skin or visible underneath. As with planes, lines and points are imaginary. Examples include:

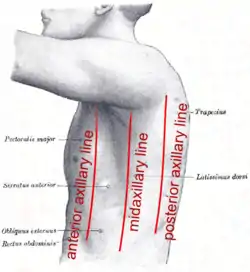

- The midaxillary line, a line running vertically down the surface of the body passing through the apex of the axilla (armpit). Parallel are the anterior axillary line, which passes through the anterior axillary skinfold, and the posterior axillary line, which passes through the posterior axillary skinfold.

- The mid-clavicular line, a line running vertically down the surface of the body passing through the midpoint of the clavicle.

In addition, reference may be made to structures at specific levels of the spine (e.g. the 4th cervical vertebra, abbreviated "C4"), or the rib cage (e.g., the 5th intercostal space).

Occasionally, in medicine, abdominal organs may be described with reference to the trans-pyloric plane, which is a transverse plane passing through the pylorus.

Comparative embryology

In discussing the neuroanatomy of animals, particularly rodents used in neuroscience research, a simplistic convention has been to name the sections of the brain according to the homologous human sections. Hence, what is technically a transverse (orthogonal) section with respect to the body length axis of a rat (dividing anterior from posterior) may often be referred to in rat neuroanatomical coordinates as a coronal section, and likewise a coronal section with respect to the body (i.e. dividing ventral from dorsal) in a rat brain is referred to as transverse. This preserves the comparison with the human brain, whose length axis in rough approximation is rotated with respect to the body axis by 90 degrees in the ventral direction. It implies that the planes of the brain are not necessarily the same as those of the body.

However, the situation is more complex, since comparative embryology shows that the length axis of the neural tube (the primordium of the brain) has three internal bending points, namely two ventral bendings at the cervical and cephalic flexures (cervical flexure roughly between the medulla oblongata and the spinal cord, and cephalic flexure between the diencephalon and the midbrain), and a dorsal (pontine or rhombic flexure) at the midst of the hindbrain, behind the cerebellum. The latter flexure mainly appears in mammals and sauropsids (reptiles and birds), whereas the other two, and principally the cephalic flexure, appear in all vertebrates (the sum of the cervical and cephalic ventral flexures is the cause of the 90 degree angle mentioned above in humans between body axis and brain axis). This more realistic concept of the longitudinal structure of vertebrate brains implies that any section plane, except the sagittal plane, will intersect variably different parts of the same brain as the section series proceeds across it (relativity of actual sections with regard to topological morphological status in the ideal unbent neural tube). Any precise description of a brain section plane therefore has to make reference to the anteroposterior part of the brain to which the description refers (e.g., transverse to the midbrain, or horizontal to the diencephalon). A necessary note of caution is that modern embryologic orthodoxy indicates that the brain's true length axis finishes rostrally somewhere in the hypothalamus where basal and alar zones interconnect from left to right across the median line; therefore, the axis does not enter the telencephalic area, although various authors, both recent and classic, have assumed a telencephalic end of the axis. The causal argument for this lies in the end of the axial mesoderm -mainly the notochord, but also the prechordal plate- under the hypothalamus. Early inductive effects of the axial mesoderm upon the overlying neural ectoderm is the mechanism that establishes the length dimension upon the brain primordium, jointly with establishing what is ventral in the brain (close to the axial mesoderm) in contrast with what is dorsal (distant from the axial mesoderm). Apart from the lack of a causal argument for introducing the axis in the telencephalon, there is the obvious difficulty that there is a pair of telencephalic vesicles, so that a bifid axis is actually implied in these outdated versions.

History

Some of these terms come from Latin. Sagittal means "like an arrow", a reference to the position of the spine that naturally divides the body into right and left equal halves, the exact meaning of the term "midsagittal", or to the shape of the sagittal suture, which defines the sagittal plane and is shaped like an arrow.

See also

References

- ↑ Kinetic Anatomy With Web Resource—3rd Edition. Human Kinetics. 2012. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-4504-3391-4.

- ↑ "How are the different head and MRI coordinate systems defined?". FieldTrip. FieldTrip. 2019-08-26. Retrieved 2019-09-24.