Albert Hale Sylvester | |

|---|---|

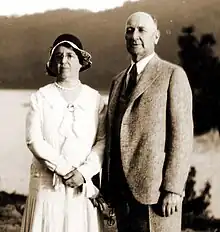

Albert H. Sylvester and his wife Alice | |

| Born | May 25, 1871 San Mateo, California, United States |

| Died | September 14, 1944 (aged 73) Wenatchee, Washington, United States |

Albert Hale Sylvester (May 25, 1871 – September 14, 1944) was a pioneer surveyor, explorer, and forest supervisor in the Cascade Range of the U.S. state of Washington. He was a topographer for the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in the Snoqualmie Ranger District between 1897 and 1907. Then, from 1908 to 1931, he served the United States Forest Service as the first forest supervisor of Wenatchee National Forest. His work involved the first detailed surveying and mapping of large portions of the Cascade Range in Washington, over the course of which he gave names to over 1,000 natural features. The surveying work often required placing cairns and other survey targets on top of mountains. He made the first ascents of a number of mountains in Washington. Over the course of his career he explored areas previously unknown to non-indigenous people. One such area, which Sylvester discovered, explored, and named, is The Enchantments. In 1944, while leading a party of friends to one of his favorite parts of the mountains, Sylvester was mortally wounded when his horse panicked and lost his footing on a steep and rocky slope.

He once wrote that of all the many places he had explored and visited in the Cascades he thought the most beautiful was the Buck Creek area, near Buck Creek Pass at the crest of the Cascades in northeast Chelan County. Buck Creek flows southeast to the Chiwawa River.[1]

Place naming

Albert H. Sylvester named over 1,000—perhaps as many as 3,000[2] natural features in the Cascade Range, including Enchantment Lakes, Dishpan Gap, Lake Margaret, Lake Ethel, Lake Mary, Lake Florence, Lake Flora, Kodak Peak, the "Poets' Ridge" peaks Irving, Poe, Longfellow, Bryant, and Whittier. Of the Enchantment Lakes area, now a very popular backpacking destination known as The Enchantments, he wrote, "it was an enchanting scene. I named the group Enchantment Lakes."[3]

During his career the region between Snoqualmie Pass and the North Cascades, where he did most of his work, was frequently updated with new maps showing the results of ongoing USGS and Forest Service surveying and exploring. This made it possible for Sylvester's place names to become well established and used. His prolific place naming was due in part to Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of the Forest Service. During the Pinchot era national forests were relatively new and often largely unmapped and lacking in place names. In order to better protect the forests from wildfire it was necessary to have names for natural features and detailed maps so that fires could be located by name and fire fighters sent to the right places. In regions like the Wenatchee National Forest there were a large number of unnamed features. Significant parts of the mountains were essentially unexplored, except by Native Americans and, in some areas, prospectors, who tended to be secretive about their discoveries. Thus Sylvester found himself exploring and mapping a large region with relatively few established names and what amounted to a mandate to bestow names.[3]

Sylvester described his experience: I didn't contact the habit [place naming] very intensely in the survey [USGS]... Coming into the Forest Service and finding that in fire protection work it was very desirable, even imperative, that the natural features capable of being named should have names as an aid in locating fire and sending in crews to combat them, I began place-naming more diligently.[4]

Sylvester's place names are scattered over much of the central and northern Cascades in Washington. They are particularly dense in the Wenatchee Mountains, Entiat Mountains, Chelan Mountains, and the Glacier Peak area, today's Glacier Peak Wilderness. In some river basins, such as the Chiwawa River, Little Wenatchee River, White River, and Entiat River basins, nearly every stream and peak was named by Sylvester.

His naming was often creative, patterned, sometimes practical and descriptive, sometimes whimsical. Examples of patterned place naming include Aurora Creek and Borealis Ridge, Choral and Anthem Creeks ("singing streams"), all in the upper Entiat valley; the three "baking powder creeks", Royal, Crescent, and Schilling Creeks, named for then-popular brands of baking powder; the American poets' peaks Bryant Peak (for William Cullen Bryant), Irving Peak (for Washington Irving), Longfellow Mountain (Henry Wadsworth Longfellow), Poe Mountain (for Edgar Allan Poe), and Whittier Peak (for John Greenleaf Whittier). He named Indian Pass and Indian Creek for the ancient Indian trail over the pass, and in association he named nearby Indian Head Peak and Papoose Creek, a tributary of Indian Creek. Near Indian Creek he named Kloochman Creek and Tillicum Creek, Chinook Jargon terms for wife and friend, "figuring that an Indian should have both a wife and a friend". Labyrinth Mountain was named for the appearance of its complex contour lines on a map, and in association Sylvester named Minotaur and Theseus Lakes on the mountain. He named Mount David and Mount Jonathan, close to one another, and Mount Saul across Indian Creek valley from them, as in Biblical history Saul being close to but forever separated from David and Jonathan.[5]

His whimsical and unusual names are among those most remarked upon. Overcoat Peak was given its name because when Sylvester climbed the mountain in 1897 to build a survey target cairn he left his overcoat, which had proven too small for comfort, buttoned around the cairn. Dirtyface Peak was named for its discolored snow banks due to rapid spring melting. Dishpan Gap was named after he found an old rusty dishpan there. Fifth of July Mountain simply denotes the day Sylvester visited the area, but stands in contrast to a number of Fourth of July place names in the region. Kodak Peak was named for a Kodak camera his assistant Willett Ramsdell lost there. Pass-No-Pass was given its name because, in Sylvester's words, "the pass has neither road nor trail, and is suited only for driving sheep from one range to another".[5]

Some of his names honor specific people, famous or obscure. For example, Mount Fernow (the highest peak in the Entiat Mountains) for Bernhard Fernow, Mount Maude for Frederick Stanley Maude, Harding Mountain for then-president Warren G. Harding, Big Jim Mountains for James J. Hill, Cool Creek for the prospector Thomas Cool, Carne Mountain for the English clergyman W. Stanely Carnes, Estes Butte for an old settler with mining claims there, Lake Jason for Forest Ranger Jason P. Williams; McCall Mountain for Lieut. J. K. McCall, U.S. Army, who was involved in Washington Territory's Indian Wars of 1858 (Sylvester renamed this peak because he felt its earlier name, Huckleberry Mountain, was too common); Phelps Creek and Phelps Ridge for a prospector.[5] He even named Klone Peak after his dog Klone.[6]

In naming lakes Sylvester began a tradition, continued by many others, of naming lakes for women. Examples include Lake Alice, for his wife; Lake Margaret and Lake Mary for the sisters of ranger Brune Canby, and Lake Florence for a friend of the Canby sisters; Lake Augusta, for his mother; Lake Ethel, for the wife of Forest Service Ranger Frank Lenzie;[7] Lake Ida, for his sister-in-law; Josephine Lake, for the wife of ranger Jason Williams; Lake Edna, for the sweetheart of a forest ranger; Lake Flora, for the wife of ranger Otto Green; Lake Grace, for the wife of Charles Haydon with whom Sylvester was exploring; Lake Lorraine, for the wife of Assistant Supervisor C. J. Conover; and Loch Eileen, for the daughter of ranger Jason Williams.[5]

In some cases his reason for giving a certain name is not obvious from the name alone. Candy Creek in the upper Entiat valley, was named for its sweet taste, but nearby Cool Creek was named for the prospector Thomas Cool. Cardinal Peak was not named for the bird but for its "supremacy among adjacent mountains"—it is the highest peak of the Chelan Mountains. He named Crook Mountain for the Army officer George Crook who served in the Washington Cascades in 1858 and later in the Civil War as a general. In the case of Crook Mountain Sylvester did not name so much as rename—the peak had been known as Goat Mountain, but Sylvester thought there were "more Goat Mountains than goats in the Northwest". Sylvester did not have a horse die on Deadhorse Pass but rather used the term given by sheepmen who used the pass. Garland Peak and Garland Creek were named for a man who grazed sheep in the area. Grindstone Mountain was named in association with Grindstone Creek, in which Sylvester found a small grindstone which had fallen from a pack horse fording the creek. Lake Sally Ann, near Dishpan Gap, appears to be another lake named for a specific woman, but Sylvester invented the name, saying "the name seemed to fit like a hand in a glove". Tinpan Mountain was given its name for no reason. Sylvester said "it was just a name for a place needing naming".[5]

Other notable places named by Sylvester include Seven Fingered Jack, Fortress Mountain, Tumwater Canyon, Jove Peak, Helmet Butte, Flower Dome, Dome Peak, Ladies Pass, Lake Valhalla, Napeequa River (previously known as the North Fork White River), Natopac Mountain, Pinnacle Mountain, Rampart Mountain, Rock Mountain, Round Mountain, Spanish Camp Creek, Wenatchee Pass and White Pass (named after the Wenatchee River and White River).[5]

Mountaineering

Albert H. Sylvester climbed many mountains in the Cascades, often for surveying purposes. Many of his climbs were first ascents. In 1897 and 1898, working as a surveyor for the USGS, Sylvester made a number of first ascents. These included, in 1897, Mount Baring, White Chuck Mountain, Columbia Peak, Overcoat Peak, and Sahale Peak. And in 1898, Snoqualmie Mountain, Gardner Mountain, Star Peak, and Reynolds Peak. These ascents were mainly for the purpose of setting up cairns, poles, and other survey targets for triangulation purposes. In some cases others may have made an earlier, unrecorded ascent. Fred Beckey writes that Sylvester made the "apparent first ascent" of Sahale Peak, "probably the first" ascent of Columbia Peak, and that Snoqualmie Mountain may have been ascended for a railroad survey in 1867 and an earlier USGS survey party may have reached the summit earlier in the 1890s.[8][9][10]

Death

In September 1944 Sylvester took three friends on a trip into the mountains. They had two pack horses in addition to a saddle horse for each traveler. Their trip went up Chiwaukum Creek to Lake Chiwaukum, then on to Larch Lake, Ewing Basin, and Cup Lake. From Cup Lake the trail grew rough and steep. They continued over Deadhorse Pass and south to the vicinity of Snowgrass Mountain. While pausing at a high point between Lake Mary and Lake Florence Sylvester's horse panicked and ran off the trail bucking. One of the pack horses was lashed to the horn of Sylvester's saddle and the rope caught his leg, holding him in the saddle as both horses fell down a steep and rocky slope. The accident left Sylvester seriously injured. Rescuers carried him out of the mountains. He was taken to a hospital in Wenatchee, but within a week he had died of his injuries.[4][11]

Legacy

In addition to the many place names established by Sylvester there are places named for him. After his death friends requested that Snowgrass Mountain be renamed for Sylvester but the request was denied. Sylvester Lake, southwest of the mountain, was the alternate idea. The lake is located at the head of Grindstone Creek near Alice Lake, which Sylvester had named for his wife. A creek on the upper Green River in King County was renamed from Forsythe Creek to Sylvester Creek by Professor A.H. Landes of the University of Washington in honor of Albert H. Sylvester.[5]

References

- ↑ "Washington Place Names Database". Tacoma Public Library. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2009. A search on "Buck Creek".

- ↑ "Preliminary Guide to the Albert Hale Sylvester Papers". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- 1 2 Klippert, Jan P. (March 2006). "Hiking Place Names: The stories behind names in the backcountry" (PDF). Washington Trails.

- 1 2 Marler, Chester (2004). East of the Divide: Travels through the Eastern Slope of the North Cascades 1870-1999. North Fork Books. pp. 25, 29–31. ISBN 0-9754605-0-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Details on places named by Sylvester from "Washington Place Names Database". Tacoma Public Library. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2009. A "Keyword search Request" on "Sylvester" returns over 200 results.

- ↑ Roe, JoAnn (2002). Stevens Pass: The Story of Railroading and Recreation in the North Cascades. Caxton Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-87004-428-1.

- ↑ Barnes, Jeremy and Nathan (2019). Alpine Lakes Wilderness: The Complete Hiking Guide. Mountaineers Books. p. Section 78. ISBN 978-1680510782.

- ↑ Beckey, Fred (2000). Cascade Alpine Guide: Climbing and High Routes: Columbia River to Stevens Pass (3rd ed.). The Mountaineers. pp. 168, 187, 300. ISBN 978-0-89886-577-6.

- ↑ Beckey, Fred (2003). Cascade Alpine Guide: Climbing and High Routes: Stevens Pass to Rainy Pass (3rd ed.). The Mountaineers. pp. 41–42, 77, 114, 331. ISBN 0-89886-423-2.

- ↑ Washington's Highest Mountains - First Ascent Chronology, Rhinoclimbs.com

- ↑ Dow, Edson (1964). Adventure in the Northwest. Outdoor Publishing.