Azbakeya (Arabic: أزبكية; also spelled Al Uzbakeya or Auzbekiya[1][2][3]) is one of the districts of the Western Area of Cairo, Egypt.[4] Along with Wust Albalad (Downtown) and Abdeen, Azbakiya forms Cairo's 19th century expansion outside the medieval city walls known officially as Khedival Cairo and declared as an Area of Value.[5][6] It holds many historically important buildings and spaces. One of these is the Saint Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral, which was inaugurated by Pope Mark VIII in 1800[7] and served as the seat of the Pope of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria from 1800 to 1971. Azbakeya was the place where the first Cairo Opera House was established, in 1869.

Administrative divisions and population

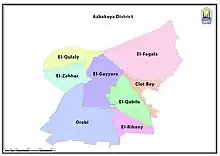

In 2017, Azbakiya diatrict/qism had 19,763 residents in its eight shiakhas:[8][9]

| Nom | Code 2017 | Population totale |

|---|---|---|

| `Urâbî | 012007 | 2027 |

| Fajjâla, al- | 012004 | 2833 |

| Jayyâra, al- | 012001 | 837 |

| Klût Bây (Clot bey) | 012008 | 1522 |

| Qabîla, al- | 012005 | 4039 |

| Qulalî, al- | 012006 | 3439 |

| Rîḥânî, al- | 012002 | 953 |

| Zahhâr, al- | 012003 | 4113 |

History

._Vue_de_la_place_Ezbekyeh_(Ezbek%C3%AEya)%252C_c%C3%B4t%C3%A9_du_sud_(NYPL_b14212718-1268752)_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The district of Azbakeya was built upon a place of an old Coptic village, Tiandonias (Coptic: ϯⲁⲛⲧⲱⲛⲓⲁⲥ) or Umm Dunayn (Arabic: ام دنين) which was also called al-Maks (Arabic: المكس "customs") in latter sources and Ottoman documents.[10][11]

By the time of Barquq, the first Burji Mamluk sultan (1382-1399), a lot of reconstruction needed to be done within the walls of the city in order to repair the damages incurred as a result of the Black Death. In 1384, when Barquq started his madrasa in Bayn al-Qasrayn, markets were rebuilt, and Khan al-Khalili, the most famous touristic market in Cairo, was established.

Al-Maqrizi showed that the northern cemetery, founded by al-Nasir Muhammad, contained no building at all before his third reign. When al-Nasir Muhammad in 1320 abandoned the area between Bab al-Nasr cemetery and the Muqattam, a small number of buildings started to be built in the northern cemetery.

Under the Burji Mamluks, northern cemetery became the new area targeted for the any new city expansion, since no ideological oppositions were found preventing the construction of dwelling within cemeteries. The lack of opposition allowed for the construction of striking religious buildings of monumental scale in the northern cemetery. Examples include the Khanqah of Faraj ibn Barquq, Madrasa of Al-Nasir Muhammad, the Emir Qurqumas Complex, the Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan al-Ashraf Barsbay and the Complex of Sultan al-Ashraf Qaytbay.

During the latter half of the 15th century, two final major transformations took place in Cairo: the port of Boulaq, and a district called Azbakeya in the northwest section of the city. The parameters of the city had been unchanged for the past 300 years according to the map done by the French expedition in 1798. With Baibars's conquest of Cyprus in 1428, Bulaq became the major port of Cairo. By the end of the 15th century, Bulaq was even able to take over the role as the major commercial port from Old Cairo.

The Azbakeya district was developed when Amir Azbak al-Yusufi, one of Qaytbay’s princes, established stables and a residence of his own and excavated Birkat al-Azbakeya, which was fed from the Cairo Citadel Aqueduct. With the Arab's Gulf always serving as the western boundary of the city and feeding nearby ponds, flooding would occur during the summer. After each flooding, surrounding lands would be transformed into lush green areas with vegetation. These beauty of the land in these areas were exquisite and the upper class fought over the each other for the first pick of the land to buy for the construction of their new palaces overlooking such bodies of water as Birkat al Fīl "Elephant Pond" and Azbakeya Pond.

Cairo in fifteenth century

Cairo was often referred to as "Misr", or Egypt, which implies that Cairo was often considered to be synonymous to Egypt whereas other cities in Egypt were of far less significance.

Meshullam Menahem wrote in 1481 "if it were possible to place all the cities of Rome, Milan, Padua, and Florence (all are Italian cities) with four other cities, they would not contain the wealth and population of half of Cairo.[12]

When the Arabs ruled Egypt, all the lands were assumed to be owned by the Caliph who distributed some among his military chiefs and farmed out the rest to its former proprietors in return for the poll tax (jizya) required for non-Muslims. By the Ayyubid period, the Iqta`a or feudal system was well established and was continued by the Mamluks as an important source of revenue.

Although the Mamluk Amirs owned large pieces of agriculture lands in various parts of Egypt, they did not reside on them. In comparison with the European of that time, the majordomo residing on the land and managed it controlled the village rarely had the chance to go to the capital. The Mamluks used to visit their lands infrequently either for supervision or the collection of the profits.

The Mamluk class was not a community, as Max Weber explains that class is a number of people have in common a specific causal component of their life chances. This component is represented exclusively by economic interests in possession of goods and opportunities for income and is represented under the conditions of the commodity or labour markets. Cairo was the centre of trade for the caravans, joining the east with the west and most of the profitable commercial deals were done in through its commercial centres. The Ambitious Mamluks preferred to live in Cairo seeking economic power that guarantees a social class within the amirs. This social benefit may lead to a better position in the royal hierarchy. The conspiracies, murders and imprisoning were a phenomenon that subsisted for the entire period of the Mamluk rule. Being in the midst of the political centre will allow for greater political awareness of any conspiracies.

Cairo as the capital had many religious institutions, Markets with the best goods that might not be available in the rural areas, Hammams and a social life that was never competed by any other major city in Egypt.

The Mamluk Amir would like to enjoy all the luxuries services that were concentrated in the capital, treating himself to compensate the tough life that any Mamluk would have lived; a childhood slavery, battles and campaigns, high economic position struggle and political participation. As a result of the centralization practice, the distribution of people in Egypt was adversely affected since a large percentage of the working class from rural cities and from all over the world strove to live in the Cairo where they could sell more and make more money. It is worth noting that this regime continues as an existing problem in contemporary Egypt.

To stay in the city of Cairo, the Amirs tried hard to urbanize new areas, and the districts would bear their name. Amir Azbak Tanakh al-Zahiry constructed the western area from the khalij in (880AH/1476 AD), and the region was called Azbakeya. Gamal al-Din Yusuf al-Ustadar constructed the area Rahbat Bab al-`id and supplied it with water from al-Khalij an-Nasiri and called it El Gamaliya.

A brief survey of any famous Mamluk street would show that there was a competition among the Amires not only in the acquisition by Mamluks to gain or maintain power but also in the construction of buildings to show off their wealth and power. Some of the Amires were more popular as builders than their Sultans like al-Qadi Yahya by the time of Sultan Jaqmaq (1438-1453 AD)

Modern history

The Egyptian Museum was established by the Egyptian government in 1835 near the Azbakeya Gardens.[13] The museum soon moved to Boulaq in 1858 because the original building was too small to hold all of the artifacts.

In the 1850s, the area was renovated during the rule of Isma'il Pasha in his plan to build a modern Cairo. Currently the well known Soor Elazbakeya (meaning the fence of Azbakeya) is a used books market [14] that originated by a gathering of used books traders by the fence of the Azbakeya garden in 1926. The market relocated to El Darasa in 1991 whilst a Metro station was being built, but returned to its original location in 1998.[15]

The Azbakeya gardens theater was the stage to most of the monthly concerts held by the late, most famous and most beloved Arab singer, Umm Kulthum. The Azbakeya gardens is only partially present now as two multi-story car parks have been built on large areas of the gardens.

References

- ↑ Guide to Palestine and Egypt. London: MacMillon and Co., Limited. 1901. pp. 162-166.

- ↑ Sladen, Douglas (1911). Oriental Cairo: The City of the "Arabian Nights". Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company. pp. xiii, 45, 54–63. ISBN 9785877802247.

- ↑ "Crisis en Egipto: Más de 70 muertos en nuevo día de enfrentamientos" [Crisis in Egypt: More than 70 dead in a new day of fighting]. La Segunda (in Spanish). Empresa El Mercurio SAP. August 16, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ↑ "Western Area". www.cairo.gov.eg. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ "Khedivial Cairo". egymonuments.gov.eg. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ↑ Khedival Cairo protection boundaries (PDF) (in Arabic). Cairo: National Organistation for Urban Harmony. 2022.

- ↑ "shababchristian". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics (CAPMAS) (2017). "2017 Census for Population and Housing Conditions". CEDEJ-CAPMAS. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- ↑ The interactive census site is the only available source with data at the shiakha level and must be queried as follows: Statistics and analysis > Population > 2017 Data > Gender >Statistical Tables >Total population and population by sex by shiyâkha/qarya > Choose location.

- ↑ Gabra, Gawdat; Takla, Hany N. (2017). Christianity and Monasticism in Northern Egypt: Beni Suef, Giza, Cairo, and the Nile Delta. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-977-416-777-5.

- ↑ Amelineau, Emile (1980). La Géographie de l'Egypte À l'Époque Copte. Paris. p. 491.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Western Travellers in the Islamic world Part 1 PDF file" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-09. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ Johnson-Roehr, S. N. (11 August 2023). "Making Egypt's Museums". JSTOR Daily.

- ↑ 10 best Archived December 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Street Smart: Souq El Azbakeya, a haven for book lovers". Ahram Online.