| Akurgal 𒀀𒆳𒃲 | |

|---|---|

| King of Lagash | |

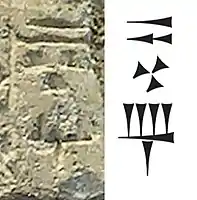

Akurgal as son of Ur-Nanshe, on the votive relief of Ur-Nanshe. The name of Akurgal (𒀀𒆳𒃲) appears on the skirt, vertically. The character next to it to the left is 𒌉, dumu, for "child", "son".[1] Louvre Museum | |

| Reign | c. 2450 BC |

| Predecessor | Ur-Nanshe |

| Successor | Eannatum |

| Dynasty | 1st Dynasty of Lagash |

Akurgal (Sumerian: 𒀀𒆳𒃲, "Descendant of the Great Mountain" in Sumerian)[2] was the second king (Ensi) of the first dynasty of Lagash.[3] His relatively short reign took place in the first part of the 25th century BCE (circa 2464-2455 BCE), during the period of the archaic dynasties.[3] He succeeded his father, Ur-Nanshe, founder of the dynasty, and was replaced by his son Eannatum.[3]

Very little is known about his reign: only six inscriptions mention it.[4] One of them reports that he built the Antasura of Ningirsu.

During his reign, a border conflict pitted Lagash against Umma,[3][5] These borders between Umma and Lagash had been fixed in ancient times by Mesilim, king (lugal) of Kish, who had drawn the borders between the two states in accordance with the oracle of Ishtaran, invoked as intercessor between the two cities. Akurgal is mentioned fragmentally in an inscription on the Stele of the Vultures, describing the conflict of Akurgal with Lagash, possibly with Ush, king of Umma: "Because of […] the man of Umma spoke arrogantly with him and defied Lagash. Akurgal, king of Lagash, son of Urnanshe […]".[6] In all likelihood Akurgal lost part of the territory of Lagash to the ruler of Umma.[7]

He had two sons, who both became important rulers of Lagash after him, Eannatum and En-anna-tum I, and successfully repelled Umma's encroachment.[3]

Shell inlay in the name of Akurgal (on the skirt, vertically), found in Girsu. Louvre Museum

Shell inlay in the name of Akurgal (on the skirt, vertically), found in Girsu. Louvre Museum Akurgal as a child in the limestone votive relief of Ur-Nanshe

Akurgal as a child in the limestone votive relief of Ur-Nanshe The name "Akurgal"

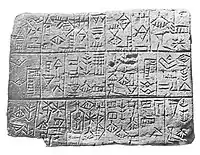

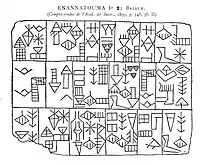

The name "Akurgal" Tablet mentioning Akurgal, as father of Enannatum I: "Enannatum, ensi of Lagash, son of Akurgal, ensi of Lagash...."[8]

Tablet mentioning Akurgal, as father of Enannatum I: "Enannatum, ensi of Lagash, son of Akurgal, ensi of Lagash...."[8] Tablet mentioning Akurgal, as father of Enannatum I: "Enannatum, ensi of Lagash, son of Akurgal, ensi of Lagash...."[8]

Tablet mentioning Akurgal, as father of Enannatum I: "Enannatum, ensi of Lagash, son of Akurgal, ensi of Lagash...."[8]

References

- ↑ "Sumerian dictionary". oracc.iaas.upenn.edu.

- ↑ "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kramer, Samuel Noah (2010). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-0-226-45232-6.

- ↑ Kramer, Samuel Noah (2010). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-226-45232-6.

- ↑ King, Leonard W. (1994). A history of Sumer and Akkad. Рипол Классик. p. 118. ISBN 978-5-87664-034-5.

- 1 2 Sallaberger, Walther; Schrakamp, Ingo (2015). History & Philology (PDF). Walther Sallaberger & Ingo Schrakamp (eds), Brepols. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-2-503-53494-7.

- ↑ Lambert, Maurice (1965). "L'occupation du Girsu par Urlumma roi d'Umma". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 59 (2): 81–84. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23283258.

- 1 2 Sarzec, Ernest (1896). Découvertes en Chaldée... L. Heuzey. p. Plate XLVI. Archived from the original on 2021-03-07. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- ↑ Découvertes en Chaldée... / publiées par L. Heuzey . 1ère-4ème livraisons / Ernest de Sarzec - Choquin de Sarzec, Ernest (1832-1901). pp. Plate XL. Archived from the original on 2021-03-07. Retrieved 2020-03-25.