| Blighia sapida | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Sapindaceae |

| Genus: | Blighia |

| Species: | B. sapida |

| Binomial name | |

| Blighia sapida | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Cupania sapida Voigt | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

9.55 g | |

| Dietary fiber | 3.45 g |

18.78 g | |

8.75 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 9% 0.10 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 15% 0.18 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 25% 3.74 mg |

| Vitamin C | 78% 65 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 8% 83 mg |

| Iron | 42% 5.52 mg |

| Phosphorus | 14% 98 mg |

Raw arils after pods allowed to open naturally. Seeds removed | |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

The ackee, also known as acki, akee, or ackee apple (Blighia sapida), is a fruit of the Sapindaceae (soapberry) family, as are the lychee and the longan. It is native to tropical West Africa.[2][3] The scientific name honours Captain William Bligh who took the fruit from Jamaica to the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, England, in 1793.[2] The English common name is derived from the West African Akan akye fufo.[4]

Although having a long-held reputation as being poisonous with potential fatalities,[5] the fruit arils are renowned as delicious when ripe, prepared properly, and cooked[6] and are a feature of various Caribbean cuisines.[2] Ackee is the national fruit of Jamaica and is considered a delicacy.[6]

Botany

Ackee is an evergreen tree that grows about 10 metres tall, with a short trunk and a dense crown.[2] The leaves are paripinnately,[7] compound 15–30 centimetres (5.9–11.8 in) long, with 6–10 elliptical to oblong leathery leaflets. Each leaflet is 8–12 centimetres (3.1–4.7 in) long and 5–8 centimetres (2.0–3.1 in) wide. The inflorescences are fragrant, up to 20 cm long, with unisexual flowers that bloom during warm months.[8] Each flower has five greenish-white petals, which are fragrant.[2][9]

The fruit is pear-shaped and has 3 lobes (2–4 lobes are common).[10] When it ripens it turns from green to a bright red to yellow-orange and splits open to reveal three large, shiny black seeds, each partly surrounded by soft, creamy or spongy, white to yellow flesh — the aril having a nut-like flavor and texture of scrambled eggs.[2][7] The fruit typically weighs 100–200 grams (3.5–7.1 oz).[7] The tree can produce fruit throughout the year, although January–March and October–November are typically periods of fruit production.[10]

_Bobo-Dioulasso%252CBF_thu14nov2013-1025h.jpg.webp) Leaves, upper and lower surface

Leaves, upper and lower surface

Fruit as it splits upon ripening "smile"

Fruit as it splits upon ripening "smile"%252Cseed%2526aril_Bobo-Dioulasso%252CBF_sun10nov2013-1740h.jpg.webp) Showing ripe fruit and seeds with their arils

Showing ripe fruit and seeds with their arils%252Cseed%2526aril(i-s)_Bobo-Dioulasso%252CBF_thu14nov2013-0953h.jpg.webp) Part of ripe fruit, two seeds with their arils still attached

Part of ripe fruit, two seeds with their arils still attached_Bobo-Dioulasso%252CBF_thu14nov2013-0953h.jpg.webp) Ripe seeds with their arils (dorsal view and in longitudinal section)

Ripe seeds with their arils (dorsal view and in longitudinal section)

Cultivars

There are up to as many as forty-eight cultivars of ackee, which are grouped into either "butter" or "cheese" types.[11] The cheese type is pale yellow in color and is more robust and finds use in the canning industry. The butter type is deeper yellow in color, and is more delicate and better suited for certain cuisine.[11]

History and culinary use

Imported to Jamaica from West Africa before 1773,[2][12] the use of ackee in Jamaican cuisine is prominent. Ackee is the national fruit of Jamaica,[6] whilst ackee and saltfish is the official national dish of Jamaica.[13]

The ackee is allowed to open fully before picking in order to eliminate toxicity. When it has "yawned" or "smiled", the seeds are discarded and the fresh, firm arils are parboiled in salted water or milk, and may be fried in butter to create a dish.[2] In Caribbean cooking, they may be cooked with codfish and vegetables, or may be added to stew, curry, soup or rice with seasonings.[2]

Nutrition

Ackee contains a moderate amount of carbohydrates, protein, and fat,[2] providing 51-58% of the dry weight of the arils as composed of fatty acids – linoleic, palmitic, and stearic acids.[14] The raw fruit is a rich source of vitamin C.[2]

Society and culture

The ackee is prominently featured in the Jamaican mento style folksong "Linstead Market". In the song, a market seller laments, "Carry mi ackee go a Linstead market. Not a quattie worth sell".[15] The Beat's 1982 album Special Beat Service includes the song "Ackee 1-2-3".[16]

Saltfish 'n Ackee is the preferred breakfast of Quarrel in the James Bond novel, Dr No.

Toxicity

The unripened aril and the inedible portions of the fruit contain hypoglycin toxins including hypoglycin A and hypoglycin B, known as "soapberry toxins".[5][17] Hypoglycin A is found in both the seeds and the arils, while hypoglycin B is found only in the seeds.[7] Minimal quantities of the toxin are found in the ripe arils.[18] In the unripe fruit, depending on the season and exposure to the sun, the concentrations may be up to 10 to 100 times greater.[18]

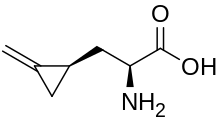

These two molecules are converted in the body to methylenecyclopropylacetic acid (MCPA), and are toxic with potential lethality.[5] MCPA and hypoglycin A inhibit several enzymes involved in the breakdown of acyl CoA compounds, often binding irreversibly to coenzyme A, carnitine and carnitine acyltransferase I and II,[19] reducing their bioavailability and consequently inhibiting beta oxidation of fatty acids. Glucose stores are consequently depleted leading to hypoglycemia,[20] and to a condition called Jamaican vomiting sickness.[2][17] These effects occur only when the unripe aril (or an inedible part of the fruit) is consumed.[2][17][21]

Though ackee is used widely in traditional dishes, research on its potential hypoglycin toxicity has been sparse and preliminary, requiring evaluation in well-designed clinical research to better understand its pharmacology, food uses, and methods for detoxification.[22]

In 2011, it was found that as the fruit ripens, the seeds act as a sink whereby the hypoglycin A in the arils convert to hypoglycin B in the seeds.[23] In other words, the seeds help in detoxifying the arils, bring the concentration of hypoglycin A to a level which is generally safe for consumption.[24]

Commercial use

Ackee canned in brine is a commodity item and is used for export by Jamaica, Haiti and Belize.[25] If propagated by seed, trees will begin to fruit in 3 – 4 years. Cuttings may yield fruit in 1 – 2 years.[25][11]

Other uses

The fruit has various uses in West Africa and in rural areas of the Caribbean Islands, including use of its "soap" properties as a laundering agent or fish poison.[2] The fragrant flowers may be used as decoration or cologne, and the durable heartwood used for construction, pilings, oars, paddles and casks.[2] In African traditional medicine, the ripe arils, leaves or bark were used to treat minor ailments.[2]

Vernacular names in African languages

| Language | Word | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Bambara | finsan | akee apple |

| Kabiye | kpɩ́zʋ̀ʋ̀ | akee apple |

| Yoruba | iṣin[26] | |

| Dagaare | kyira |

References

- ↑ IUCN SSC Global Tree Specialist Group & Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) (2019). "Blighia sapida". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T146420481A156104704. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Morton, JF (1987). "Ackee; Blighia sapida K. Konig". Fruits of warm climates. Miami, FL: The Center for New Crops and Plant Products, at Purdue University. pp. 269–271. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ↑ "Blighia sapida". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ↑ Metcalf, Allan (1999). The World in So Many Words. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-95920-9.

- 1 2 3 Isenberg, Samantha L.; Carter, Melissa D.; Hayes, Shelby R.; Graham, Leigh Ann; Johnson, Darryl; Mathews, Thomas P.; Harden, Leslie A.; Takeoka, Gary R.; Thomas, Jerry D.; Pirkle, James L.; Johnson, Rudolph C. (13 July 2016). "Quantification of toxins in soapberry (Sapindaceae) arils: Hypoglycin A and methylenecyclopropylglycine". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 64 (27): 5607–5613. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b02478. ISSN 0021-8561. PMC 5098216. PMID 27367968.

- 1 2 3 "Ackee". Jamaican Information Service. 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Vinken Pierre; Bruyn, GW (1995). Intoxications of the Nervous System. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science B.V. ISBN 0-444-81284-9.

- ↑ Llamas, Kristen (2003). Tropical Flowering Plants: A Guide to Identification and Cultivation. Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-585-3.

- ↑ Riffle, Robert (1998). The Tropical Look. Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-422-9.

- 1 2 Gordon, André (2 June 2015). Food safety and quality systems in developing countries. Volume one, Export challenges and implementation strategies. London. ISBN 978-0-12-801351-9. OCLC 910662541.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 Sinmisola, Aloko; Oluwasesan, Bello M.; Chukwuemeka, Azubuike P. (May 2019). "Blighia sapida K.D. Koenig: A review on its phytochemistry, pharmacological and nutritional properties". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 235: 446–459. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.01.017. PMID 30685434. S2CID 195661482.

- ↑ "This is Jamaica". National Symbols of Jamaica. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2006.

- ↑ "Top 10 National Dishes". National Geographic Traveller. 13 September 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ↑ "Jamaican Ackee". wwwchem.uwimona.edu.jm. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ↑ "Ackee - Jamaican National Symbol". Jamaica Information Service. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ↑ "Ackee 1 2 3 - The English Beat". Allmusic.com. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- 1 2 3 Isenberg, Samantha L.; Carter, Melissa D.; Graham, Leigh Ann; Mathews, Thomas P.; Johnson, Darryl; Thomas, Jerry D.; Pirkle, James L.; Johnson, Rudolph C. (2 September 2015). "Quantification of metabolites for assessing human exposure to soapberry toxins hypoglycin A and methylenecyclopropylglycine". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 28 (9): 1753–1759. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00205. ISSN 0893-228X. PMC 4592145. PMID 26328472.

- 1 2 Seeff, Leonard; Stickel, Felix; Navarro, Victor J. (1 January 2013), Kaplowitz, Neil; DeLeve, Laurie D. (eds.), "Chapter 35 - Hepatotoxicity of Herbals and Dietary Supplements", Drug-Induced Liver Disease (3 ed.), Boston: Academic Press, pp. 631–657, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-387817-5.00035-2, ISBN 978-0-12-387817-5, retrieved 5 July 2020

- ↑ Kumar, Parveen J. (2006). Clinical Medicine (5 ed.). Saunders (W.B.) Co Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7020-2579-2.

- ↑ SarDesai, Vishwanath (2003). Introduction to Clinical Nutrition. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc. ISBN 0-8247-4093-9.

- ↑ Andrea Goldson (16 November 2005). "The ackee fruit (Blighia sapida) and its associated toxic effects". The Science Creative Quarterly.

- ↑ Sinmisola, Aloko; Oluwasesan, Bello M.; Chukwuemeka, Azubuike P. (10 May 2019). "Blighia sapida K.D. Koenig: A review on its phytochemistry, pharmacological and nutritional properties". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 235: 446–459. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.01.017. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 30685434. S2CID 195661482.

- ↑ Bowen-Forbes, Camille S.; Minott, Donna A. (27 April 2011). "Tracking hypoglycins A and B over different maturity stages: implications for detoxification of ackee (Blighia sapida K.D. Koenig) fruits". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 59 (8): 3869–3875. doi:10.1021/jf104623c. ISSN 1520-5118. PMID 21410289.

- ↑ Blake, Orane A.; Bennink, Maurice R.; Jackson, Jose C. (February 2006). "Ackee (Blighia sapida) hypoglycin A toxicity: dose response assessment in laboratory rats". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 44 (2): 207–213. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2005.07.002. ISSN 0278-6915. PMID 16099087.

- 1 2 Prakash, Vishweshwaraiah; Martín-Belloso, Olga; Keener, Larry; Astley, Siân, eds. (1 January 2016), "Copyright", Regulating Safety of Traditional and Ethnic Foods, San Diego: Academic Press, pp. iv, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-800605-4.00026-8, ISBN 978-0-12-800605-4, retrieved 27 June 2020

- ↑ Bascom, William R. (January 1951). "Yoruba Food". Africa. Cambridge University Press. 20 (1): 47. doi:10.2307/1156157. JSTOR 1156157. S2CID 149837516.