| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

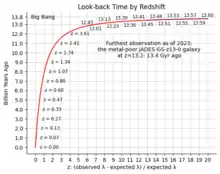

In physical cosmology, the age of the universe is the time elapsed since the Big Bang. Astronomers have derived two different measurements of the age of the universe:[1] a measurement based on direct observations of an early state of the universe, which indicate an age of 13.787±0.020 billion years as interpreted with the Lambda-CDM concordance model as of 2021;[2] and a measurement based on the observations of the local, modern universe, which suggest a younger age.[3][4][5] The uncertainty of the first kind of measurement has been narrowed down to 20 million years, based on a number of studies that all show similar figures for the age. These studies include researches of the microwave background radiation by the Planck spacecraft, the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe and other space probes. Measurements of the cosmic background radiation give the cooling time of the universe since the Big Bang,[6] and measurements of the expansion rate of the universe can be used to calculate its approximate age by extrapolating backwards in time. The range of the estimate is also within the range of the estimate for the oldest observed star in the universe.

History

−13 — – −12 — – −11 — – −10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the 18th century, the concept that the age of Earth was millions, if not billions, of years began to appear. Nonetheless, most scientists throughout the 19th century and into the first decades of the 20th century presumed that the universe itself was Steady State and eternal, possibly with stars coming and going but no changes occurring at the largest scale known at the time.

The first scientific theories indicating that the age of the universe might be finite were the studies of thermodynamics, formalized in the mid-19th century. The concept of entropy dictates that if the universe (or any other closed system) were infinitely old, then everything inside would be at the same temperature, and thus there would be no stars and no life. No scientific explanation for this contradiction was put forth at the time.

In 1915 Albert Einstein published the theory of general relativity[7] and in 1917 constructed the first cosmological model based on his theory. In order to remain consistent with a steady-state universe, Einstein added what was later called a cosmological constant to his equations. Einstein's model of a static universe was proved unstable by Arthur Eddington.

The first direct observational hint that the universe was not static but expanding came from the observations of 'recession velocities', mostly by Vesto M. Slipher, combined with distances to the 'nebulae' (galaxies) by Edwin Hubble in a work published in 1929.[8] Earlier in the 20th century, Hubble and others resolved individual stars within certain nebulae, thus determining that they were galaxies, similar to, but external to, our Milky Way Galaxy. In addition, these galaxies were very large and very far away. Spectra taken of these distant galaxies showed a red shift in their spectral lines presumably caused by the Doppler effect, thus indicating that these galaxies were moving away from the Earth. In addition, the farther away these galaxies seemed to be (the dimmer they appeared to us) the greater was their redshift, and thus the faster they seemed to be moving away. This was the first direct evidence that the universe is not static but expanding. The first estimate of the age of the universe came from the calculation of when all of the objects must have started speeding out from the same point. Hubble's initial value for the universe's age was very low, as the galaxies were assumed to be much closer than later observations found them to be.

The first reasonably accurate measurement of the rate of expansion of the universe, a numerical value now known as the Hubble constant, was made in 1958 by astronomer Allan Sandage.[10] His measured value for the Hubble constant came very close to the value range generally accepted today.

Sandage, like Einstein, did not believe his own results at the time of discovery. Sandage proposed new theories of cosmogony to explain this discrepancy. This issue was more or less resolved by improvements in the theoretical models used for estimating the ages of stars. As of 2013, using the latest models for stellar evolution, the estimated age of the oldest known star is 14.46±0.8 billion years.[11]

The discovery of microwave cosmic background radiation announced in 1965[12] finally brought an effective end to the remaining scientific uncertainty over the expanding universe. It was a chance result from work by two teams less than 60 miles apart. In 1964, Arno Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson were trying to detect radio wave echoes with a supersensitive antenna. The antenna persistently detected a low, steady, mysterious noise in the microwave region that was evenly spread over the sky, and was present day and night. After testing, they became certain that the signal did not come from the Earth, the Sun, or our galaxy, but from outside our own galaxy, but could not explain it. At the same time another team, Robert H. Dicke, Jim Peebles, and David Wilkinson, were attempting to detect low level noise that might be left over from the Big Bang and could prove whether the Big Bang theory was correct. The two teams realized that the detected noise was in fact radiation left over from the Big Bang, and that this was strong evidence that the theory was correct. Since then, a great deal of other evidence has strengthened and confirmed this conclusion, and refined the estimated age of the universe to its current figure.

The space probes WMAP, launched in 2001, and Planck, launched in 2009, produced data that determines the Hubble constant and the age of the universe independent of galaxy distances, removing the largest source of error.[13]

Explanation

The Lambda-CDM concordance model describes the evolution of the universe from a very uniform, hot, dense primordial state to its present state over a span of about 13.77 billion years[14] of cosmological time. This model is well understood theoretically and strongly supported by recent high-precision astronomical observations such as WMAP. In contrast, theories of the origin of the primordial state remain very speculative.

If one extrapolates the Lambda-CDM model backward from the earliest well-understood state, it quickly (within a small fraction of a second) reaches a singularity. This is known as the "initial singularity" or the "Big Bang singularity". This singularity is not understood as having a physical significance in the usual sense, but it is convenient to quote times measured "since the Big Bang" even though they do not correspond to a time that can actually be physically measured.

Though the universe might in theory have a longer history, the International Astronomical Union[15] presently uses the term "age of the universe" to mean the duration of the Lambda-CDM expansion, or equivalently, the time elapsed within the currently observable universe since the Big Bang.

Observational limits

Since the universe must be at least as old as the oldest things in it, there are a number of observations that put a lower limit on the age of the universe;[16][17] these include

- the temperature of the coolest white dwarfs, which gradually cool as they age, and

- the dimmest turnoff point of main sequence stars in clusters (lower-mass stars spend a greater amount of time on the main sequence, so the lowest-mass stars that have evolved away from the main sequence set a minimum age).

Cosmological parameters

The problem of determining the age of the universe is closely tied to the problem of determining the values of the cosmological parameters. Today this is largely carried out in the context of the ΛCDM model, where the universe is assumed to contain normal (baryonic) matter, cold dark matter, radiation (including both photons and neutrinos), and a cosmological constant.

The fractional contribution of each to the current energy density of the universe is given by the density parameters and The full ΛCDM model is described by a number of other parameters, but for the purpose of computing its age these three, along with the Hubble parameter , are the most important.

If one has accurate measurements of these parameters, then the age of the universe can be determined by using the Friedmann equation. This equation relates the rate of change in the scale factor to the matter content of the universe. Turning this relation around, we can calculate the change in time per change in scale factor and thus calculate the total age of the universe by integrating this formula. The age is then given by an expression of the form

where is the Hubble parameter and the function depends only on the fractional contribution to the universe's energy content that comes from various components. The first observation that one can make from this formula is that it is the Hubble parameter that controls that age of the universe, with a correction arising from the matter and energy content. So a rough estimate of the age of the universe comes from the Hubble time, the inverse of the Hubble parameter. With a value for around 69 km/s/Mpc, the Hubble time evaluates to 14.5 billion years.[18]

To get a more accurate number, the correction function must be computed. In general this must be done numerically, and the results for a range of cosmological parameter values are shown in the figure. For the Planck values (0.3086, 0.6914), shown by the box in the upper left corner of the figure, this correction factor is about For a flat universe without any cosmological constant, shown by the star in the lower right corner, is much smaller and thus the universe is younger for a fixed value of the Hubble parameter. To make this figure, is held constant (roughly equivalent to holding the cosmic microwave background temperature constant) and the curvature density parameter is fixed by the value of the other three.

Apart from the Planck satellite, the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) was instrumental in establishing an accurate age of the universe, though other measurements must be folded in to gain an accurate number. CMB measurements are very good at constraining the matter content [19] and curvature parameter [20] It is not as sensitive to directly,[20] partly because the cosmological constant becomes important only at low redshift. The most accurate determinations of the Hubble parameter are currently believed to come from measured brightnesses and redshifts of distant Type Ia supernovae. Combining these measurements leads to the generally accepted value for the age of the universe quoted above.

The cosmological constant makes the universe "older" for fixed values of the other parameters. This is significant, since before the cosmological constant became generally accepted, the Big Bang model had difficulty explaining why globular clusters in the Milky Way appeared to be far older than the age of the universe as calculated from the Hubble parameter and a matter-only universe.[21][22] Introducing the cosmological constant allows the universe to be older than these clusters, as well as explaining other features that the matter-only cosmological model could not.[23]

WMAP

NASA's Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) project's nine-year data release in 2012 estimated the age of the universe to be (13.772±0.059)×109 years (13.772 billion years, with an uncertainty of plus or minus 59 million years).[6]

This age is based on the assumption that the project's underlying model is correct; other methods of estimating the age of the universe could give different ages. Assuming an extra background of relativistic particles, for example, can enlarge the error bars of the WMAP constraint by one order of magnitude.[24]

This measurement is made by using the location of the first acoustic peak in the microwave background power spectrum to determine the size of the decoupling surface (size of the universe at the time of recombination). The light travel time to this surface (depending on the geometry used) yields a reliable age for the universe. Assuming the validity of the models used to determine this age, the residual accuracy yields a margin of error near one per cent.[13]

Planck

In 2015, the Planck Collaboration estimated the age of the universe to be 13.813±0.038 billion years, slightly higher but within the uncertainties of the earlier number derived from the WMAP data.[25]

In the table below, figures are within 68% confidence limits for the base ΛCDM model.

Cosmological parameters from 2015 Planck results[25] Parameter Symbol TT + lowP TT + lowP + lensing TT + lowP + lensing + ext TT, TE, EE + lowP TT, TE, EE + lowP + lensing TT, TE, EE + lowP + lensing + ext Age of the universe

(Ga)13.813±0.038 13.799±0.038 13.796±0.029 13.813±0.026 13.807±0.026 13.799±0.021 Hubble constant

(km⁄Mpc⋅s)67.31±0.96 67.81±0.92 67.90±0.55 67.27±0.66 67.51±0.64 67.74±0.46

Legend:

- TT, TE, EE: Planck Cosmic microwave background (CMB) power spectra

- lowP: Planck polarization data in the low-ℓ likelihood

- lensing: CMB lensing reconstruction

- ext: External data (BAO+JLA+H0). BAO: Baryon acoustic oscillations, JLA: Joint Light curve Analysis, H0: Hubble constant

In 2018, the Planck Collaboration updated its estimate for the age of the universe to 13.787±0.020 billion years.[2]

Assumption of strong priors

Calculating the age of the universe is accurate only if the assumptions built into the models being used to estimate it are also accurate. This is referred to as strong priors and essentially involves stripping the potential errors in other parts of the model to render the accuracy of actual observational data directly into the concluded result. This is not a valid procedure in all contexts, as noted in the accompanying caveat: "on the assumption that the project's underlying model is correct". The age given is thus accurate to the specified error, however, since this error represents the error in the instrument used to gather the raw data input into the model.

The age of the universe based on the best fit to Planck 2018 data alone is 13.787±0.020 billion years. This number represents an accurate "direct" measurement of the age of the universe, in contrast to other methods that typically involve Hubble's law and the age of the oldest stars in globular clusters. It is possible to use different methods for determining the same parameter (in this case, the age of the universe) and arrive at different answers with no overlap in the "errors". To best avoid the problem, it is common to show two sets of uncertainties; one related to the actual measurement and the other related to the systematic errors of the model being used.

An important component to the analysis of data used to determine the age of the universe (e.g. from Planck) therefore is to use a Bayesian statistical analysis, which normalizes the results based upon the priors (i.e. the model).[13] This quantifies any uncertainty in the accuracy of a measurement due to a particular model used.[26][27]

See also

- Age of Earth – Scientific dating of the age of Earth

- Anthropic principle – Hypothesis about sapient life and the universe

- Cosmic Calendar – Method to visualize the chronology of the universe (age of the universe scaled to a single year)

- Dark Ages Radio Explorer – Proposed concept lunar orbiter

- Expansion of the universe – Increase in distance between parts of the universe over time

- Hubble Deep Field – Multiple exposure image of deep space in the constellation Ursa Major

- Illustris project – Computer-simulated universes

- James Webb Space Telescope – NASA/ESA/CSA space telescope launched in 2021

- Multiverse – Hypothetical group of multiple universes

- Observable universe – All of space observable from the Earth at the present

- Observational cosmology – Study of the origin of the universe (structure and evolution)

- Redshift observations in astronomy – Change of wavelength in photons during travel

- Static universe – Cosmological model in which the universe does not expand

- The First Three Minutes – 1977 book by Steven Weinberg

- Timeline of the far future – Scientific projections regarding the far future

References

- ↑ "From an almost perfect Universe to the best of both worlds". Planck mission. sci.esa.int. European Space Agency. 17 July 2018. last paragraphs. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020.

- 1 2 Planck Collaboration (2020). "Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 641. page A6 (see PDF page 15, Table 2: "Age/Gyr", last column). arXiv:1807.06209. Bibcode:2020A&A...641A...6P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833910. S2CID 119335614.

- ↑ Riess, Adam G.; Casertano, Stefano; Yuan, Wenlong; Macri, Lucas; Bucciarelli, Beatrice; Lattanzi, Mario G.; et al. (12 July 2018). "Milky Way cepheid standards for measuring cosmic distances and application to Gaia DR2: Implications for the Hubble constant". The Astrophysical Journal. 861 (2): 126. arXiv:1804.10655. Bibcode:2018ApJ...861..126R. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aac82e. ISSN 1538-4357. S2CID 55643027.

- ↑ ESA/Planck Collaboration (17 July 2018). "Measurements of the Hubble constant". sci.esa.int. European Space Agency. Archived from the original on 6 October 2020.

- ↑ Freedman, Wendy L.; Madore, Barry F.; Hatt, Dylan; Hoyt, Taylor J.; Jang, In-Sung; Beaton, Rachael L.; et al. (29 August 2019). "The Carnegie-Chicago Hubble Program. VIII. An independent determination of the Hubble constant based on the tip of the red giant branch". The Astrophysical Journal. 882 (1): 34. arXiv:1907.05922. Bibcode:2019ApJ...882...34F. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab2f73. ISSN 1538-4357. S2CID 196623652.

- 1 2 Bennett, C.L.; et al. (2013). "Nine-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observations: Final maps and results". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 208 (2): 20. arXiv:1212.5225. Bibcode:2013ApJS..208...20B. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/208/2/20. S2CID 119271232.

- ↑ Einstein, A. (1915). "Zur allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie" [On the general theory of relativity]. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (in German): 778–786. Bibcode:1915SPAW.......778E.

- ↑ Hubble, E. (1929). "A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 15 (3): 168–173. Bibcode:1929PNAS...15..168H. doi:10.1073/pnas.15.3.168. PMC 522427. PMID 16577160.

- 1 2 S.V. Pilipenko (2013-2021) "Paper-and-pencil cosmological calculator" arxiv:1303.5961, including Fortran-90 code upon which the citing charts and formulae are based.

- ↑ Sandage, A. R. (1958). "Current Problems in the Extragalactic Distance Scale". The Astrophysical Journal. 127 (3): 513–526. Bibcode:1958ApJ...127..513S. doi:10.1086/146483.

- ↑ Bond, H. E.; Nelan, E. P.; Vandenberg, D. A.; Schaefer, G. H.; Harmer, D. (2013). "HD 140283: A Star in the Solar Neighborhood that Formed Shortly After the Big Bang". The Astrophysical Journal. 765 (12): L12. arXiv:1302.3180. Bibcode:2013ApJ...765L..12B. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/765/1/L12. S2CID 119247629.

- ↑ Penzias, A. A.; Wilson, R .W. (1965). "A Measurement of Excess Antenna Temperature at 4080 Mc/s". The Astrophysical Journal. 142: 419–421. Bibcode:1965ApJ...142..419P. doi:10.1086/148307.

- 1 2 3 Spergel, D.N.; et al. (2003). "First-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observations: Determination of cosmological parameters". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 148 (1): 175–194. arXiv:astro-ph/0302209. Bibcode:2003ApJS..148..175S. doi:10.1086/377226. S2CID 10794058.

- ↑ "Cosmic Detectives". European Space Agency. 2 April 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Chang, K. (9 March 2008). "Gauging age of universe becomes more precise". The New York Times.

- ↑ Chaboyer, Brian (1 December 1998). "The age of the universe". Physics Reports. 307 (1–4): 23–30. arXiv:astro-ph/9808200. Bibcode:1998PhR...307...23C. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(98)00054-4. S2CID 119491951.

- ↑ Chaboyer, Brian (16 February 1996). "A Lower Limit on the Age of the Universe". Science. 271 (5251): 957–961. arXiv:astro-ph/9509115. Bibcode:1996Sci...271..957C. doi:10.1126/science.271.5251.957. S2CID 952053.

- ↑ Liddle, A. R. (2003). An Introduction to Modern Cosmology (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-470-84835-7.

- ↑ Hu, W. "Animation: Matter Content Sensitivity. The matter-radiation ratio is raised while keeping all other parameters fixed". University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 23 February 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- 1 2 Hu, W. "Animation: Angular diameter distance scaling with curvature and lambda". University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 23 February 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- ↑ "Globular Star Clusters". SEDS. 1 July 2011. Archived from the original on 24 February 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Iskander, E. (11 January 2006). "Independent age estimates". University of British Columbia. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- ↑ Ostriker, J.P.; Steinhardt, P.J. (1995). "Cosmic concordance". arXiv:astro-ph/9505066.

- ↑ de Bernardis, F.; Melchiorri, A.; Verde, L.; Jimenez, R. (2008). "The Cosmic Neutrino Background and the Age of the Universe". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2008 (3): 20. arXiv:0707.4170. Bibcode:2008JCAP...03..020D. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2008/03/020. S2CID 8896110.

- 1 2 Planck Collaboration (2016). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 594. page A13 (see PDF page 32, Table 4: "Age/Gyr", last column). arXiv:1502.01589. Bibcode:2016A&A...594A..13P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830. S2CID 119262962.

- ↑ Loredo, T. J. (1992). "The Promise of Bayesian Inference for Astrophysics" (PDF). In Feigelson, E. D.; Babu, G. J. (eds.). Statistical Challenges in Modern Astronomy. Springer-Verlag. pp. 275–297. Bibcode:1992scma.conf..275L. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-9290-3_31. ISBN 978-1-4613-9292-7.

- ↑ Colistete, R.; Fabris, J. C.; Concalves, S. V. B. (2005). "Bayesian statistics and parameter constraints on the generalized Chaplygin gas model Using SNe ia data". International Journal of Modern Physics D. 14 (5): 775–796. arXiv:astro-ph/0409245. Bibcode:2005IJMPD..14..775C. doi:10.1142/S0218271805006729. S2CID 14184379.

External links

- Wright, Ned. "Cosmology tutorial". Division of Astronomy & Astrophysics (academic personal site). University of California, Los Angeles.

- Wright, Edward L. (2 July 2005). "Age of the Universe". Division of Astronomy & Astrophysics (academic personal site). University of California, Los Angeles.

- Hu, Wayne. "cosmological parameter animations" (academic personal site). U. Chicago.

- Ostriker, J.P.; Steinhardt, P.J. (1995). "Cosmic concordance". arXiv:astro-ph/9505066.

- "Globular star clusters". SEDS. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015.

- Scott, Douglas. "Independent age estimates" (academic personal site). Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia.

- "The scale of the universe". KryssTal. — Space and time set to scale for the beginner.

- "Cosmology calculator (with graph generation)". iCosmos.

- "The Expanding Universe". American Institute of Physics.