| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History | ||||||

| Lists and outlines | ||||||

| Theory and criticism | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Adventure fiction is a type of fiction that usually presents danger, or gives the reader a sense of excitement. Some adventure fiction also satisfies the literary definition of romance fiction.[1]

History

In the Introduction to the Encyclopedia of Adventure Fiction, Critic Don D'Ammassa defines the genre as follows:

.. An adventure is an event or series of events that happens outside the course of the protagonist's ordinary life, usually accompanied by danger, often by physical action. Adventure stories almost always move quickly, and the pace of the plot is at least as important as characterization, setting, and other elements of creative work.[2]

D'Ammassa argues that adventure stories make the element of danger the focus; hence he argues that Charles Dickens's novel A Tale of Two Cities is an adventure novel because the protagonists are in constant danger of being imprisoned or killed, whereas Dickens's Great Expectations is not because "Pip's encounter with the convict is an adventure, but that scene is only a device to advance the main plot, which is not truly an adventure."[2]

Adventure has been a common theme since the earliest days of written fiction. Indeed, the standard plot of Heliodorus, and so durable as to be still alive in Hollywood movies, a hero would undergo a first set of adventures before he met his lady. A separation would follow, with the second set of adventures leading to a final reunion.

Variations kept the genre alive. From the mid-19th century onwards, when mass literacy grew, adventure became a popular subgenre of fiction. Although not exploited to its fullest, adventure has seen many changes over the years – from being constrained to stories of knights in armor to stories of high-tech espionage.

Examples of that period include Sir Walter Scott, Alexandre Dumas, père,[3] Jules Verne, Brontë Sisters, H. Rider Haggard, Victor Hugo,[4] Emilio Salgari, Karl May, Louis Henri Boussenard, Thomas Mayne Reid, Sax Rohmer, Talbot Mundy, Edgar Wallace, and Robert Louis Stevenson.

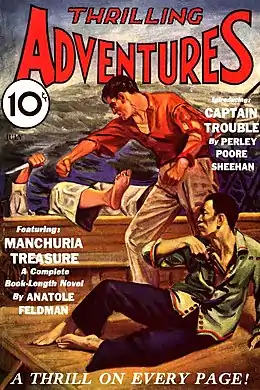

Adventure novels and short stories were popular subjects for American pulp magazines, which dominated American popular fiction between the Progressive Era and the 1950s.[5] Several pulp magazines such as Adventure, Argosy, Blue Book, Top-Notch, and Short Stories specialized in this genre. Notable pulp adventure writers included Edgar Rice Burroughs, Talbot Mundy, Theodore Roscoe, Johnston McCulley, Arthur O. Friel, Harold Lamb, Carl Jacobi, George F. Worts,[5] Georges Surdez, H. Bedford-Jones, and J. Allan Dunn.[6]

Adventure fiction often overlaps with other genres, notably war novels, crime novels, detective novels, sea stories, Robinsonades, spy stories (as in the works of John Buchan, Eric Ambler and Ian Fleming), science fiction, fantasy, (Robert E. Howard and J. R. R. Tolkien both combined the secondary world story with the adventure novel)[7] and Westerns. Not all books within these genres are adventures. Adventure fiction takes the setting and premise of these other genres, but the fast-paced plot of an adventure focuses on the actions of the hero within the setting. With a few notable exceptions (such as Baroness Orczy, Leigh Brackett and Marion Zimmer Bradley)[8] adventure fiction as a genre has been largely dominated by male writers, though female writers are now becoming common.

For children

Adventure stories written specifically for children began in the 19th century. Early examples include Johann David Wyss's The Swiss Family Robinson (1812), Frederick Marryat's The Children of the New Forest (1847), and Harriet Martineau's The Peasant and the Prince (1856).[9] The Victorian era saw the development of the genre, with W. H. G. Kingston, R. M. Ballantyne, and G. A. Henty specializing in the production of adventure fiction for boys.[10] This inspired writers who normally catered to adult audiences to essay such works, such as Robert Louis Stevenson writing Treasure Island for a child readership.[10] In the years after the First World War, writers such as Arthur Ransome developed the adventure genre by setting the adventure in Britain rather than distant countries, while Geoffrey Trease, Rosemary Sutcliff[11] and Esther Forbes brought a new sophistication to the historical adventure novel.[10] Modern writers such as Mildred D. Taylor (Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry) and Philip Pullman (the Sally Lockhart novels) have continued the tradition of the historical adventure.[10] The modern children's adventure novel sometimes deals with controversial issues like terrorism (Robert Cormier, After the First Death, (1979))[10] and warfare in the Third World (Peter Dickinson, AK, (1990)).[10]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Essay on Romance", Prose Works volume vi, p. 129, quoted in "Introduction" to Walter Scott's Quentin Durward, ed. Susan Maning. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992, p. xxv.

- 1 2 D'Ammassa, Don. Encyclopedia of Adventure Fiction. Facts on File Library of World Literature, Infobase Publishing, 2009 (pp. vii-viii).

- ↑ Green, Martin Burgess. Seven Types of Adventure Tale: An Etiology of A Major Genre. Penn State Press, 1991 (pp. 71–2).

- ↑ Taves, Brian. The Romance of Adventure: The Genre of Historical Adventure Movies.University Press of Mississippi, 1993 (p. 60)

- 1 2 Server,Lee. Danger is My Business: An Illustrated History of the Fabulous Pulp Magazines. Chronicle Books, 1993 (pp. 49–60).

- ↑ Robinson, Frank M. and Davidson, Lawrence. Pulp Culture – The Art of Fiction Magazines. Collectors Press Inc. 2007 (pp. 33–48).

- ↑ Pringle, David. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London, Carlton pp. 33–5

- ↑ Richard A. Lupoff.Master of Adventure: The Worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs. University of Nebraska Press, 2005 (pp.194, 247)

- ↑ Hunt, Peter. (Editor). Children's literature: an illustrated history. Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-19-212320-3 (pp. 98–100)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Butts, Dennis, "Adventure Books" in Zipes, Jack, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. Volume One. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-19-514656-1 (pp. 12–16).

- ↑ Hunt, 1995, (pp. 208–9)