Abigail Fillmore | |

|---|---|

| |

| First Lady of the United States | |

| In role July 9, 1850 – March 4, 1853 | |

| President | Millard Fillmore |

| Preceded by | Margaret Taylor |

| Succeeded by | Jane Pierce |

| Second Lady of the United States | |

| In role March 4, 1849 – July 9, 1850 | |

| Vice President | Millard Fillmore |

| Preceded by | Sophia Dallas |

| Succeeded by | Mary Breckinridge |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Abigail Powers March 13, 1798 Stillwater, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 30, 1853 (aged 55) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

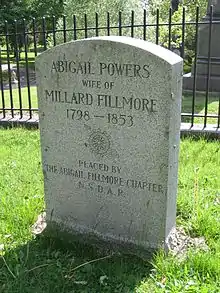

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo, New York |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Signature | |

Abigail Fillmore (née Powers; March 13, 1798 – March 30, 1853), wife of President Millard Fillmore, was the first lady of the United States from 1850 to 1853. She began work as a schoolteacher at the age of 16, where she took on Millard Fillmore, who was two years her junior, as a student. She continued her teaching work after their marriage in 1826 until the birth of her son Millard Powers Fillmore in 1828. She lived in Buffalo, New York, while her husband advanced his political career in Albany, New York, and Washington, D.C. She would occasionally join him in these cities, becoming involved in local social life. She became the second lady of the United States in 1849 after her husband was elected vice president on the Whig Party presidential ticket, and she became the first lady of the United States in 1850 after her husband succeeded to the presidency.

Fillmore's most noted achievement as first lady was the establishment of the first White House Library. She had a lifelong appreciation for literature and refused to live in a home without books. The library became a popular reception room in the White House and functioned as the home of a literary salon. She was also involved in the political aspects of the presidency, and her husband often sought her opinion on state affairs. She took less interest in the role of White House hostess, and she suffered from ailments that prevented her from carrying out some of her duties, including an injured ankle that limited her mobility. Many of her social responsibilities were delegated to her daughter Mary Abigail Fillmore. Fillmore died of pneumonia in 1853, mere weeks after the end of her tenure as first lady. She has received little historical attention; she is considered one of the most obscure first ladies, and much of her correspondences are lost.

Early life and education

Abigail Powers was born in Stillwater, New York, on March 13, 1798, in Saratoga County.[1] She was the youngest of seven children born to Reverend Lemuel Powers and Abigail Newland. Her father was the leader of the First Baptist Church until he died when she was two years old. After Lemuel's death, the family moved to Sempronius, New York.[2]: 182 They moved in with Abigail's older brother Cyrus Powers because of their impoverished state. Her father had left behind a large library of his personal books, which Abigail read extensively.[1] Her mother was a schoolteacher who used these books to teach her to read and to appreciate her education.[3]: 87–88 She came to love literature and also became proficient in other subjects such as math, government, history, philosophy, and geography.[1] She was also made familiar with abolitionism as a child, as the Baptist faith opposed slavery and her family was friends with local abolitionist George Washington Jonson.[2]: 184

Powers began a career as a schoolteacher at the age of 16, which would eventually make her the first first lady to have previously pursued a career.[4] In 1814, Abigail became a part-time school teacher at the Sempronius Village school. In 1817, she became a full-time teacher, and in 1819, she took on another teaching job at the private New Hope Academy.[1] She advanced her own education by alternating her teaching and her studies at the school.[2]: 182 She continued studying further subjects after leaving school, learning to speak French and play the piano.[5]

Marriage and family

While teaching at New Hope Academy, she took on Millard Fillmore as a student.[3]: 88 They were engaged in 1819, but they did not marry for several years.[6]: 83 Millard was not wealthy enough to support a family, and Abigail's family discouraged her from marrying the son of a dirt farmer.[7]: 84 They remained in contact as they pursued separate teaching careers over the following years.[8] In 1824, she became a private tutor in Lisle to three of her cousins. She was then asked to open up a private school in Broome County; she opened the school, and in 1825, she went back to Sempronius to teach in her original position,[1] where she would found a library.[3]: 88 While they were apart, they once went as long as three years without seeing one another.[9]: 155–156

Abigail and Millard married in her brother's house in Moravia, New York, on February 5, 1826, after Millard had become an attorney,[2]: 181–182 and they moved to East Aurora, New York.[7]: 84 Though women teachers were often expected to resign after marriage, Abigail continued to teach until she had children.[8] The Fillmores had two children: their son Millard Powers Fillmore was born in 1828, and their daughter Mary Abigail "Abbie" Fillmore was born in 1832.[2]: 183 In 1830, they moved to Buffalo, New York, which Millard helped establish. He was a member of the New York State Assembly at this time, and Abigail was responsible for tending to the house and children on her own while he was away for work.[2]: 183 She would often lament his absences, fearing he would meet a new woman while he was away.[3]: 89 While in Buffalo, they joined the local Unitarian Church.[7]: 84 Millard also started a law practice in the city, and its success brought the Fillmores a comfortable life with financial security.[9]: 156 She saw to the construction of Buffalo's first public library, and she grew her own personal collection until it reached 4,000 books.[8] She was also responsible for naming the town of Newstead, New York, in 1831, suggesting the name in reference to the home of Lord Byron.[10]: 41

Washington, D.C., and Albany, New York

Millard was elected as a member of the United States House of Representatives in 1832, and Abigail stayed in Buffalo while he was in Washington, D.C. He stepped down in 1834, but he was elected again in 1836, and this time Abigail accompanied him to Washington, leaving the children with relatives in New York. Here she would fulfill the social obligations of a politician's wife, and she also sought out cultural and academic institutions in the city.[6]: 84–85 They would continue with this routine each time Congress was in session for the following years. She would write to her children regularly while away, often encouraging self-improvement and scolding them for spelling errors in their replies.[9]: 157

Abigail was well regarded in Washington social life. In 1840 she was asked to dedicate a building; it was a rare honor for a woman at the time, though she declined.[3]: 89–90 While in Washington, she sat in on a Senate debate by Henry Clay in 1837 and met Charles Dickens in 1842.[2]: 183 They returned to Buffalo after Millard left Congress in 1842, and Abigail became a popular hostess in the city. When Millard was elected New York State Comptroller, the family moved to Albany, New York, and she became involved with the social life there.[2]: 183 While she held fashionable society in contempt, she enjoyed observing people's behavior and attending parties.[9]: 160 The Fillmores separated from their children again while in Albany, this time sending them away to Massachusetts.[3]: 90

On Independence Day of 1842, she sustained an injury in her ankle.[2]: 183 While walking on an uneven sidewalk, she slipped and twisted her ankle severely enough that she was unable to walk for two weeks. When she began walking, it further inflamed her foot. She was bedridden until winter and confined to her room for several months thereafter. For the following two years, she would be forced to walk using crutches. The injury never fully healed, and she suffered from chronic pain for the rest of her life.[9]: 159

Fillmore became a prominent figure when her husband was nominated as the Whig candidate for vice president in the 1848 presidential election, and she became known to the public through a flattering description in The American Review. The Whig ticket was elected, and Abigail became the second lady of the United States in March 1849.[2]: 183 Her health made a return to Washington undesirable, and she remained in Buffalo.[7]: 85 Abigail found social life in Washington uninteresting,[4] and she spent much of her time as second lady tending to her sister, who had had a stroke.[2]: 188 She briefly visited Washington to see her husband in 1850.[9]: 160 Being the second lady meant being involved with high-profile social circles, and she expressed joy at interacting with prominent authors of the day, such as Ann S. Stephens, Lydia Sigourney, and Emma Willard.[10]: 42

First Lady of the United States

.jpg.webp)

President Zachary Taylor died in July 1850, causing Millard to become president and Abigail to become his first lady.[2]: 184 Abigail was on vacation in New Jersey with her children when President Taylor died. When she discovered that she was to be the first lady, she suffered from self-doubt, believing that she would not serve sufficiently.[3]: 91 She had become comfortable in domestic life, and she was apprehensive about the expectations that had been placed suddenly upon her.[9]: 161 She arrived at the White House the following October.[11]: 160 Her sister's death in February 1851 caused her considerable grief.[9]: 162

Within the White House, Fillmore was an active first lady who hosted many social events.[2]: 187 Though she was an active conversationalist, she did not enjoy the social aspects of the role; she found that most guests had little interest in her intellectual pursuits, and she considered them to be "cave dwellers".[5] She would often go on coach rides with her husband around Washington and the surrounding countryside.[9]: 162 She also took advantage of the cultural elements of Washington while she was first lady, regularly attending art exhibitions and concerts, breaking precedent by traveling without her husband.[3]: 92 In the summers, she would return to New York to visit friends and family.[3]: 93

The Fillmores had come from poverty, and as such they had little interest in elaborate decoration or refurnishing. Unlike many first ladies, Abigail did not extensively redecorate the White House upon entering. Instead, she designed the White House interior in the style of a middle-class home. She did, however, emphasize the use of mahogany and fine carpets.[10]: 44 She also oversaw the expansion of the White House heating system and had a kitchen stove installed to replace the practice of cooking by fireplace.[9]: 162

Abigail and Millard corresponded regularly when they were apart. Their letters often concerned politics, and she would write back offering him advice and counsel on political matters.[6]: 86 She closely followed bills in Congress and other political news, and she was able to discuss them in detail.[5] He valued her opinion, and he reportedly never made any important decision without first consulting her. Abigail may have advised her husband not to sign the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, though he eventually did.[6]: 86 She may have also encouraged him to end the practice of flogging as a punishment in the Navy.[3]: 93 Abigail would regularly receive letters from citizens asking her to speak to the president on their behalf, particularly from charities asking for donations and people asking for political patronage. One such individual was her brother David, who received a position in the Fillmore administration.[9]: 163

Due to her poor health, Fillmore delegated many of her duties to her daughter Abbie, who was responsible for meeting with callers outside of the White House.[2]: 187 Her ankle injury further complicated her role as White House hostess, and she would often be bedridden for a day after standing for hours to manage a long receiving line.[5] By the end of the Fillmore presidency, Abbie carried out most of the social aspects of the role.[3]: 91–92 One particular incident that prevented Fillmore from carrying out her duties was a second injury to her ankle in 1851 that left her incapacitated for weeks.[2]: 186 She was also relieved from further responsibilities due to the more reserved nature of social life at the White House caused by President Taylor's death and growing political polarization.[3]: 91

White House library

When Abigail first moved into the White House, she was reportedly appalled at the fact that there was no library in it.[6]: 86 [3]: 92 Previous presidents had brought their own private book collections to the White House, retaining them after the end of their presidencies. The Fillmores decided that a library was a necessary fixture in the White House, as Abigail was accustomed to having books in the home and Millard depended on reference books in his work as president.[10]: 43 With $2,000 (equivalent to $70,352 in 2022) authorized by Congress, she selected books for a White House library in the Oval Room.[6]: 86 [3]: 92 Abigail took responsibility for the organization and decoration of the room.[10]: 43 She modeled the room after the style of Andrew Jackson Downing, using cottage furniture with walnut frames.[10]: 44 Whenever new packages of books arrived, she would personally open them and place the books.[4]

The library became a social hub of the White House during the Fillmore administration. Abigail hosted writers such as William Thackeray, Charles Dickens, Washington Irving,[6]: 86 and Helen Aldrich De Kroyft and performance artists such as Anna Bishop[10]: 45 and Jenny Lind, essentially creating a White House literary salon.[6]: 86 This library became her primary focus as first lady, with it serving as a reception room, a family room, and a place of rest for her husband.[2]: 185 It also doubled as a music room, with Abbie using the room to play piano, harp, and guitar. Abigail spent a large portion of her time as first lady in her library, and Millard often spent an hour in the library at night after leaving the executive chamber.[10]: 44

Death

Abigail was the first first lady to attend the inauguration of her successor. After leaving the White House, she and her husband had begun planning travel. Their plans were interrupted when she fell ill. What started as a cold became bronchitis and then pneumonia.[6]: 88 When a doctor was called, he used an ineffective cupping and blistering technique that may have worsened her health.[9]: 163 She died of her illness in the Willard Hotel on March 30, 1853, aged 55. She was laid in state in Washington[9]: 164 and then buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, New York.[7]: 86

Washington went into a period of mourning, and much of the federal government temporarily ceased operations in respect of her death.[3]: 93 In his memoirs, Millard credited her for the support that she provided in progressing his education.[2]: 182 On February 10, 1858, five years after her death, her husband, then 58, married 44-year-old Caroline Carmichael McIntosh, a wealthy Buffalo widow. They remained married for sixteen years until Millard's death from a stroke on March 8, 1874, at the age of 74.[11]: 61

Legacy

In the years preceding the American Civil War, the position of first lady received very little public attention. Fillmore has not received significant historical coverage relative to first ladies of other eras, and is often regarded as a less active first lady.[2]: 177 She is best remembered for her organization of a library in the White House.[2]: 184 Biographers of Millard Fillmore have generally given little attention to Abigail, in part due to the lack of surviving documents. Most of her private correspondences have been lost and are presumed to have been destroyed by her son.[2]: 188 What does survive is primarily lists of books that she asked her husband to purchase while he traveled.[4] Historians disagree on the extent that her poor health and ankle injury prevented her from carrying out White House duties; some say that it was severe enough to limit her ability, while others say that it was merely an excuse to avoid the responsibilities of a first lady.[7]: 85–86 She is typically recognized as an intellectual and as a supportive influence in the president's life.[2]: 188

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "First Lady Biography: Abigail Fillmore". National First Ladies' Library. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Thacker-Estrada, Elizabeth Lorelei (2016). "Chapter Eleven: Margaret Taylor, Abigail Fillmore, and Jane Pierce: Three Antebellum Presidents' Ladies". In Sibley, Katherine A. S. (ed.). A Companion to First Ladies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 176–196. ISBN 978-1-118-73218-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Watson, Robert P. (2001). First Ladies of the United States. Lynne Rienner Publishers. pp. 87–94. doi:10.1515/9781626373532. ISBN 978-1-62637-353-2. S2CID 249333854.

- 1 2 3 4 Foster, Feather Schwartz (2011). The First Ladies: From Martha Washington to Mamie Eisenhower, an Intimate Portrait of the Women Who Shaped America. Cumberland House. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-1-4022-4272-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Caroli, Betty (2010). First Ladies: From Martha Washington to Michelle Obama. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-19-539285-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Roberts II, John B. (2003). Rating the First Ladies. New York: Citadel Press Books. pp. 82–88. ISBN 0-8065-2387-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schneider, Dorothy; Schneider, Carl J. (2010). First Ladies: A Biographical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Facts on File. pp. 83–87. ISBN 978-1-4381-0815-5.

- 1 2 3 Longo, James McMurtry (2011). From Classroom to White House: The Presidents and First Ladies as Students and Teachers. McFarland. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-7864-8846-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Gould, Lewis L. (1996). American First Ladies: Their Lives and Their Legacy. Garland Publishing. pp. 154–165. ISBN 0-8153-1479-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Parisian, Catherine M., ed. (2010). The First White House Library. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271037134.

- 1 2 Diller, Daniel C.; Robertson, Stephen L. (2001). The Presidents, First Ladies, and Vice Presidents: White House Biographies, 1789–2001. CQ Press. ISBN 9781568025735.