| Abatur | |

|---|---|

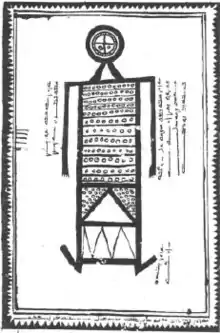

Image of Abatur from Diwan Abatur | |

| Other names | Third Life, Abatur Rama, Abatur Muzania, Bhaq Ziwa, Yawar, Ancient of Days |

| Abode | World of Light |

| Symbol | Scales |

| Texts | Diwan Abatur |

| Parents | Yushamin |

| Offspring | Ptahil |

| Equivalents | |

| Egyptian equivalent | Anubis |

| Zoroastrian equivalent | Rashnu[1] |

| Part of a series on |

| Mandaeism |

|---|

|

| Religion portal |

Abatur (ࡀࡁࡀࡕࡅࡓ, sometimes called Abathur; Yawar, ࡉࡀࡅࡀࡓ; and the Ancient of Days) is an Uthra and the second of three subservient emanations created by the Mandaean God Hayyi Rabbi (ࡄࡉࡉࡀ ࡓࡁࡉࡀ, “The Great Living God”) in the Mandaean religion. His name translates as the “father of the Uthras”, the Mandaean name for angels or guardians.[2] His usual epithet is the Ancient (Atiga) and he is also called the deeply hidden and guarded. He is described as being the son of the first emanation, or Yoshamin (ࡉࡅࡔࡀࡌࡉࡍ).[3] He is also described as being the angel of Polaris.[4]

He exists in two different personae. These include Abatur Rama (ࡀࡁࡀࡕࡅࡓ ࡓࡀࡌࡀ, the "lofty" or celestial Abatur), and his "lower" counterpart, Abatur of the Scales (ࡀࡁࡀࡕࡅࡓ ࡌࡅࡆࡀࡍࡉࡀ), who weighs the souls of the dead to determine their fate.[5] In Mandaean texts such as the Qolasta, Abatur is sometimes referred to as Bhaq Ziwa.[6]: 7–8

Etymology

Häberl (2022) etymologizes Abatur as abbā ḏ-otri 'father of the excellencies',[6]: 213 since he translates uthra as 'excellency.'[7]

Abatur in Diwan Abatur

He is one of the main characters in the Scroll of Abatur, one of the more recent texts of the Mandaeans. The text begins with a lacuna. He is said to reside on the borderland between the here and the hereafter, at the farthest verge of the World of Light that lies toward the lower regions. Beneath him was originally nothing but a huge void with muddy black water at the bottom, in which his image was reflected.[3] The existing text starts with Hibil (ࡄࡉࡁࡉࡋ, an important World of Light envoy) telling Abatur to go and reside in the boundary between the World of Light and the World of Darkness, and weigh for purity those souls which have passed through all the matarta (spiritual toll houses) and wish to return to the light.

Abatur is not happy with the assignment, complaining that he is being asked to leave his home and his wives and do this task. Abatur then rather impatiently asks a whole series of questions regarding specific sins of omission and sins of commission, asking in effect how can such impure souls be saved. Hibil then answers these questions in a rather lengthy response.

A later section of the book reveals that Abatur is the source of Ptahil (ࡐࡕࡀࡄࡉࡋ), who fills the role of the demiurge in Mandaean mythology. The book indicates how Abatur gives Ptahil-uthra precise instructions on how to create the material world (Tibil, ࡕࡉࡁࡉࡋ) in the void described above, and gives him the materials and help (in the form of demons from the World of Darkness) he needs to do so. Ptahil, like Abatur before him, complains about his assignment, but does as he is told. The world he creates is a very dark place, unlike the World of Light from which Abatur and the others come from.

After the material world is created, the Primordial Adam asks Abatur what he will do when he goes to Tibil. Abatur answers that Adam will be helped by Manda d-Hayyi, the entity which instructs humans with sacred knowledge and protects them. This enrages Ptahil, who dislikes Abatur giving a degree of control of his own creatures to someone else, and complains bitterly about it, in much the same way that Abatur had complained about his assignment to Hibil Ziwa.

He subsequently serves in his capacity as judge of the dead, in much the same capacity as Rashnu and Anubis. Those souls which qualify can enter into the World of Light from which Abatur himself came. He himself will only be allowed by Hibil to return to the World of Light upon the end of the poorly-made material world that Ptahil created.

Imagery

Images of the Mandaean beings tend to be of a blocky style vaguely reminiscent of European cubism, and this imagery, allowing for stylistic differences of individual artists, is consistent throughout the illustrated diwans. None of the celestial beings shown has any fleshy or material bodies, and this may play a part in the non-representative nature of their depictions. In the surviving images in the Diwan Abatur, Abatur is depicted sitting on a throne. Both Abatur and Ptahil are depicted as having faces divided into quarters, with what seem to be eyes in the lower two quarters of the face. Some have interpreted this as indicating that they both have to look down upon the earth.

See also

- Ancient of Days in Judaism

- Metatron in Judaism

- Anubis in Egyptian mythology

- Avatar in Hinduism

- Rashnu in Zoroastrianism

- List of angels in theology

References

- ↑ Kraeling, Carl (June 1933). "The Mandaic God Ptahil". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 53 (2): 152–165. doi:10.2307/593099. JSTOR 593099.

- ↑ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen. 2002. The Mandaeans: Ancient Texts and Modern People. Oxford: Oxford University Press p8

- 1 2 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mandaeans". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 555–556.

- ↑ Bunson, Matthew. Angels A to Z. New York:Crown Trade Paperbacks, 1996. ISBN 0-517-88537-9

- ↑ Drower, Ethel Stefana. "105 (Known as the Asiet Malkia)". The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans. Page 105, translator's footnote 4.

⁴) There are two Abathurs, one appears to be a dmuta (or counterpart) of the other. In the less abstract form, he is Abathur of the Scales, the spirit of justice which weighs human souls in his balance.

- 1 2 Häberl, Charles (2022). The Book of Kings and the Explanations of This World: A Universal History from the Late Sasanian Empire. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-80085-627-1.

- ↑ Häberl, Charles G.; McGrath, James F. (2019). The Mandaean Book of John: Text and Translation (PDF). Open Access Version. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.