| 7th Cavalry | |

|---|---|

7th Cavalry coat of arms | |

| Active | 1866–present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Armored cavalry |

| Garrison/HQ | Fort Cavazos, Texas |

| Nickname(s) | "Garryowen" |

| Motto(s) | "Seventh First" |

| March | Garryowen[1] |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Colonel Andrew J. Smith Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer Colonel (later Major General) James W. Forsyth Lieutenant General Hal Moore Brigadier General (later Major General) Adna R. Chaffee Jr. |

| Insignia | |

| Regimental distinctive insignia |  |

| Regimental march | ⓘ |

| U.S. Cavalry Regiments | ||||

|

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen",[1] after the Irish air "Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune. The regiment participated in some of the largest battles of the Indian Wars, including its famous defeat at the Battle of Little Bighorn, where its commander Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer was killed. The regiment also committed the Wounded Knee Massacre, where more than 250 men, women and children of the Lakota were killed.

The 7th Cavalry became part of the 1st Cavalry Division in the 1920s, it went on to fight in the Pacific Theater of World War II and took part in the Admiralty Islands, Leyte and Luzon campaigns. It later participated several key battles of the Korean War. During the Korean War the unit committed the No Gun Ri massacre, in which between 250 and 300 South Korean refugees were killed, mostly women and children. The unit later participated in the Vietnam War. It distinguished itself in the Gulf War and in the Global War on Terror where its squadrons and battalions now serve as Combined Arms Battalions or as reconnaissance squadrons for Brigade Combat Teams in Iraq and Afghanistan.

American Indian Wars

At the end of the American Civil War, the ranks of the Regular cavalry regiments had been depleted by war and disease, as were those of the other Regular regiments. Of the 448 companies of cavalry, infantry, and artillery authorized, 153 were not organized, and few, if any, of these were at full strength. By July 1866 this shortage had somewhat eased since many of the members of the disbanded Volunteer outfits had by then enlisted as Regulars.[2] By that time, however, it became apparent in Washington, D.C. that the Army, even at full strength, was not large enough to perform all its duties. It needed occupation troops for the Reconstruction of the South and it needed to replace the Volunteer regiments still fighting Native Americans in the West. Consequently, on 28 July 1866 Congress authorized 4 additional cavalry regiments and enough infantry companies to reorganize the existing 19 regiments (then under two different internal organizations) into 45 regiments with 10 companies each. After this increase there were 10 regiments of cavalry, 5 of artillery, and 45 of infantry.[2] The new cavalry regiments, numbered 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th, were organized under the same tables as the 6 already in existence. A regiment consisted of 12 companies formed into 3 squadrons of 4 companies each. Besides the commanding officer who was a colonel, the regimental staff included 7 officers, 6 enlisted men, a surgeon, and 2 assistant surgeons. Each company was authorized 4 officers, 15 non-commissioned officers, and 72 privates. A civilian veterinarian accompanied the regiment although he was not included in the table of organization.

The 7th Cavalry Regiment was constituted in the Regular Army on 28 July 1866 at Fort Riley, Kansas and organized on 21 September 1866. Andrew J. Smith, a Veteran of the Mexican–American War, who had been a distinguished cavalry leader in the Army of the Tennessee during the Civil War, promoted to colonel, took command of the new regiment. Subsequently, Smith resigned from the US Army and Colonel Samuel D. Sturgis took command of the regiment on May 6, 1869. Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer had been serving as second in command of the regiment since July 1866. Neither Smith nor Sturgis served with the regiment in the field, were involved in mostly administrative matters with the regiment, and were in command in name only. Meanwhile, Custer commanded the regiment in the various campaigns against the Native American tribes and during Reconstruction duty in the southern states. Sturgis commanded the regiment until his retirement and Colonel James W. Forsyth took command of the regiment in June 1886. Forsyth commanded the regiment during the controversial Wounded Knee Massacre in December 1890 and he left the regiment in 1894 when Forsyth was promoted to brigadier general.

First campaigns

On 26 November 1868, Custer's Osage scouts located the trail of an Indian war party. Custer's troops followed this trail all day without a break until nightfall, when they rested briefly until there was sufficient moonlight to continue. They followed the trail to Chief Black Kettle's village, where Custer divided his force into four parts, moving each into position so that at first daylight they could simultaneously converge on the village.[3] (Separating his forces into several columns in order to surround the faster Indians before they could flee became one of the 7th Cavalry's standard operating procedures.) At daybreak, the 7th charged as the Regimental band played Garryowen[4] (many of the musicians' lips froze to their instruments[4]), Double Wolf awoke and fired his gun to alert the village; he was among the first to die in the charge.[5] The Cheyenne warriors hurriedly left their lodges to take cover behind trees and in deep ravines. The 7th Cavalry soon controlled the village, but it took longer to quell all remaining resistance.[6]

The Osage, enemies to the Cheyenne, were at war with most of the Plains tribes. The Osage scouts led Custer toward the village, hearing sounds and smelling smoke from the camp long before the soldiers. The Osage did not participate in the initial attack, fearing that the soldiers would mistake them for Cheyenne and shoot them. Instead, they waited behind the color-bearer of the 7th Cavalry on the north side of the river until the village was taken. The Osage rode into the village, where they took scalps and helped the soldiers round up fleeing Cheyenne women and children.[7]

Black Kettle and his wife, Medicine Woman, were shot in the back and killed while fleeing on a pony.[8][9] Following the capture of Black Kettle's village, Custer was in a precarious position. As the fighting began to subside, he saw large groups of mounted Indians gathering on nearby hilltops and learned that Black Kettle's village was only one of many Indian encampments along the river, where thousands of Indians had gathered. Fearing an attack, he ordered some of his men to take defensive positions while the others seized the Indians' property and horses. They destroyed what they did not want or could not carry, including about 675 ponies and horses. They spared 200 horses to carry prisoners.[10]

Near nightfall, fearing the outlying Indians would find and attack his supply train, Custer began marching his forces toward the other encampments. The surrounding Indians retreated, at which point Custer turned around and returned to his supply train.[11] This engagement would soon be known as the Battle of Washita River.

Yellowstone Expedition

From 20 June – 23 September 1873, Custer led ten companies of the 7th Cavalry in the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873, during which, they fought several engagements with the Lakota Sioux Indians. The first of which was the Battle of Honsinger Bluff, on 4 August 1873. Near present-day Miles City, Montana, the 7th Cavalry's horses were grazing when a raiding party led by Chief Rain-in-the-Face approached upon them. Custer ordered the men to saddle up and began pursuit of the band alongside LT Calhoun and his aide, LT William W. Cooke. The Indians retreated into a wooded area, where a hidden force of 100–300 rode out to counterattack. Custer and his men retreated, covered by C Company (led by CPT Thomas Custer, George's younger brother), and dismounted his troops, forming a semicircular perimeter along a former channel of the Yellowstone in a wooded area. The bank of the dry channel served as a natural parapet. The Indian forces laid siege to the cavalry troops, but with little effect. About an hour into the battle, a force of nearly 50 warriors attempted to flank the cavalry's perimeter by traveling down along the river. They were hidden by the high bank, however a scout accompanying them was spotted and drew fire. The group, thinking they had been discovered, retreated.[12]

The flanking tactic having failed, the Indians set fire to the grass hoping to use the smoke as a screen to approach the cavalry perimeter. However, 7th Cavalry Troopers likewise used the smoke as a screen to move closer to the Indian forces and the tactic did not favor either side.[12] The siege continued for about three hours in reported 110 °F (43 °C) heat.[13] The 7th Cavalry's senior veterinary surgeon, Dr. John Horsinger, was riding approximately 2–3 miles from the battle with Suttler Augustus Baliran, and believed the sporadic shooting in the distance to be Custer's men hunting game. When warned by an Arikara scout, he ignored him. Meanwhile, PVTs Brown and Ball of CPT Yates' Troop were napping by the river. Ball saw Dr. Horsinger and rode to join him, however, Chief Rain in the Face and five warriors ambushed the men and killed all three. PVT Brown, unnoticed by the Indians, galloped toward friendly positions yelling "All down there are killed!"[14] The remaining 7th Cavalry elements, under 2LT Charles Braden, charged the Indian positions. Simultaneously, Custer ordered his men to break out of the woods and charge, effectively scattering the Indians and forcing them to withdraw.

_and_relevant_Indian_territories.png.webp)

A few days later, on the morning of 11 August 1873, the 7th Cavalry was encamped along the north side of the Yellowstone River near present-day Custer, Montana. In the early morning hours the Battle of Pease Bottom began when warriors from the village of Sitting Bull started firing at Custer's camp from across the river. By dawn skirmishing had broken out in several locations. After shooting at least 3 warriors across the river, Private John Tuttle of Company E, 7th Cavalry was killed in the morning fighting, warriors then crossed the Yellowstone River above and below the camp of the 7th Cavalry and attacked Custer's troops. The 7th Cavalry successfully defended their rear, front and center from this attack, then counter-attacked with a charge, breaking the warrior positions and driving the warriors eight or more miles from the battlefield. At about the same time, Colonel Stanley's column appeared in the distance several miles away and hurried to support the engagement. During the battle Second Lieutenant Charles Braden of the 7th Cavalry was critically wounded, along with three other Privates of the same regiment. Braden's thigh was shattered by an Indian bullet and he remained on permanent sick leave until his retirement from the Army in 1878. He would posthumously be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in 1925 for his actions during the battle.[19] At least one army horse was wounded during the engagement. Indian losses were unknown, however, estimates from Custer's post-battle report claim "their losses in killed and wounded were beyond all proportion to that which they were enabled to inflict on us, our losses being one officer badly wounded, four men killed, and three wounded. Careful investigation justifies the statement that including both day's battles, the Indian losses will number forty warriors, while their wounded on the opposite bank of the river may increase this number."[20]

The Black Hills and Yellowstone

_and_invited_guests._Fort_A._Lincoln_on_the_Little_Heart_River%252C_-_NARA_-_530885.tif.jpg.webp)

Over the next several years, the 7th Cavalry Regiment was involved in several important missions in the American West; one of which was the Black Hills Expedition in 1874. The Troopers escorted prospectors into the Black Hills of South Dakota (considered sacred by many Indians, including the Sioux) to protect them as they searched for gold. In 1875, several 7th Cavalry Troops escorted a railroad survey team into the Yellowstone River Valley. This expedition brought them into constant contact with Native raiding parties.[4] Custer repeatedly requested to share surplus food and grain with the Indians in order to prevent conflict, but was denied by the Standing Rock Indian Agency under the Department of the Interior. Corrupt Indian agents in the area sold food, supplies, and weapons promised to the Natives to white settlers, and what they did sell to the Indians was at unreasonable prices.[4] Given their treatment at the hand of the Indian Agency, the Indians were forced to migrate. Custer found President Ulysses S. Grant's brother Orvil Grant to be the worst culprit of all. He was corrupt, paid and took bribes, and was accused of cheating, abuse, and dishonesty. President Grant promptly relieved COL Custer of his position when the latter spoke the truth about Orvil and other agents.[4]

The Battle of the Little Bighorn

General Philip H. Sheridan intervened, however, and had Custer returned to his command in early 1876 in order to join the upcoming campaign against the Dakota Sioux. Custer's 7th Cavalry Regiment would be under the command of General Alfred H. Terry, and departed Fort Abraham Lincoln on 17 May 1876. The plan for the 1876 Sioux Expedition involved three marching columns under the commands of Major General George Crook, Colonel Custer, and Major General John Gibbon. Crook's column was stopped by the Indians at the Battle of the Rosebud, leaving two columns remaining. The 7th marched on 22 June with 700 troopers and Native Scouts, and made contact with the Indians the next day, causing him to turn west towards the Little Bighorn River. On 24 June, Custer's Arikara and Osage scouts identified a party of Sioux shadowing their movements, but they fled when approached. That night, Custer gave his attack plans for 25 June 1876, precipitating the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Reno's attack

A: Custer B: Reno C: Benteen D: Yates E: Weir

The first group to attack was Major Marcus Reno's second detachment (Companies A, G and M) after receiving orders from Custer written out by Lt. William W. Cooke, as Custer's Crow scouts reported Sioux tribe members were alerting the village. Ordered to charge, Reno began that phase of the battle. The orders, made without accurate knowledge of the village's size, location, or the warriors' propensity to stand and fight, had been to pursue the Native Americans and "bring them to battle." Reno's force crossed the Little Bighorn at the mouth of what is today Reno Creek around 3:00 pm on 25 June. They immediately realized that the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne were present "in force and not running away."

Reno advanced rapidly across the open field towards the northwest, his movements masked by the thick bramble of trees that ran along the southern banks of the Little Bighorn River. The same trees on his front right shielded his movements across the wide field over which his men rapidly rode, first with two approximately forty-man companies abreast and eventually with all three charging abreast. The trees also obscured Reno's view of the Native American village until his force had passed that bend on his right front and was suddenly within arrow-shot of the village. The tepees in that area were occupied by the Hunkpapa Sioux. When Reno came into the open in front of the south end of the village, he sent his Arikara and Crow Indian scouts forward on his exposed left flank.[22] Realizing the full extent of the village's width, Reno quickly suspected what he would later call "a trap" and stopped a few hundred yards short of the encampment.

He ordered his troopers to dismount and deploy in a skirmish line, according to standard Army doctrine. In this formation, every fourth trooper held the horses for the troopers in firing position, with five to ten yards separating each trooper, officers to their rear and troopers with horses behind the officers. This formation reduced Reno's firepower by 25 percent. As Reno's men fired into the village and killed, by some accounts, several wives and children of the Sioux leader, Chief Gall (in Lakota, Phizí), the mounted warriors began streaming out to meet the attack. With Reno's men anchored on their right by the impassable tree line and bend in the river, the Indians rode hard against the exposed left end of Reno's line. After about 20 minutes of long-distance firing, Reno had taken only one casualty, but the odds against him had risen (Reno estimated five to one), and Custer had not reinforced him. Trooper Billy Jackson reported that by then, the Indians had begun massing in the open area shielded by a small hill to the left of Reno's line and to the right of the Indian village.[23] From this position the Indians mounted an attack of more than 500 warriors against the left and rear of Reno's line,[24] turning Reno's exposed left flank. They forced a hasty withdrawal into the timber along the bend in the river.[25] Here the Indians pinned Reno and his men down and set fire to the brush to try to drive the soldiers out of their position.

After giving orders to mount, dismount and mount again, Reno told his men, "All those who wish to make their escape follow me," and led a disorderly rout across the river toward the bluffs on the other side. The retreat was immediately disrupted by Cheyenne attacks at close quarters. Later, Reno reported that three officers and 29 troopers had been killed during the retreat and subsequent fording of the river. Another officer and 13–18 men were missing. Most of these missing men were left behind in the timber, although many eventually rejoined the detachment. Reno's hasty retreat may have been precipitated by the death of Reno's Arikara scout Bloody Knife, who had been shot in the head as he sat on his horse next to Reno, his blood and brains splattering the side of Reno's face.

Reno and Benteen on Reno Hill

Atop the bluffs, known today as Reno Hill, Reno's depleted and shaken troops were joined by Captain Frederick Benteen's column (Companies D, H and K), arriving from the south. This force had been returning from a lateral scouting mission when it had been summoned by Custer's messenger, Italian bugler John Martin (Giovanni Martini) with the handwritten message "Benteen. Come on, Big Village, Be quick, Bring packs. P.S. Bring Packs.".[26] Benteen's coincidental arrival on the bluffs was just in time to save Reno's men from possible annihilation. Their detachments were soon reinforced by CPT Thomas Mower McDougall's Company B and the pack train. The 14 officers and 340 troopers on the bluffs organized an all-around defense and dug rifle pits using whatever implements they had among them, including knives.

Despite hearing heavy gunfire from the north, including distinct volleys at 4:20 pm, Benteen concentrated on reinforcing Reno's badly wounded and hard-pressed detachment rather than continuing on toward Custer's position. Around 5:00 pm, Capt. Thomas Weir and Company D moved out to make contact with Custer.[26] They advanced a mile, to what is today Weir Ridge or Weir Point, and could see in the distance native warriors on horseback shooting at objects on the ground. By this time, roughly 5:25 pm, Custer's battle may have concluded. The conventional historical understanding is that what Weir witnessed was most likely warriors killing the wounded soldiers and shooting at dead bodies on the "Last Stand Hill" at the northern end of the Custer battlefield. Some contemporary historians have suggested that what Weir witnessed was a fight on what is now called Calhoun Hill, some minutes earlier. The destruction of CPT Myles Keogh's battalion may have begun with the collapse of L, I and C Company (half of it) following the combined assaults led by Crazy Horse, White Bull, Hump, Chief Gall and others.[27]: 240 Other native accounts contradict this understanding, however, and the time element remains a subject of debate. The other entrenched companies eventually followed Weir by assigned battalions, first Benteen, then Reno, and finally the pack train. Growing attacks around Weir Ridge by natives coming from the concluded Custer engagement forced all seven companies to return to the bluff before the pack train, with the ammunition, had moved even a quarter-mile. The companies remained pinned down on the bluff for another day, but the natives were unable to breach the tightly held position.

Benteen was hit in the heel of his boot by an Indian bullet. At one point, he personally led a counterattack to push back Indians who had continued to crawl through the grass closer to the soldier's positions.

Custer's fight

._Yellow_area_517_is_1851_Crow_treaty_land_ceded_to_the_U.S.png.webp)

The precise details of Custer's fight are largely conjectural since none of the men who went forward with Custer's battalion (the five companies under his immediate command) survived the battle. Later accounts from surviving Indians are useful, but sometimes conflicting and unclear.

While the gunfire heard on the bluffs by Reno and Benteen's men was probably from Custer's fight, the soldiers on Reno Hill were unaware of what had happened to Custer until General Terry's arrival on 27 June. They were reportedly stunned by the news. When the army examined the Custer battle site, soldiers could not determine fully what had transpired. Custer's force of roughly 210 men had been engaged by the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne about 3.5 miles (5.6 km) to the north of Reno and Benteen's defensive position. Evidence of organized resistance included an apparent skirmish line on Calhoun Hill and apparent breastworks made of dead horses on Custer Hill.[27] By the time troops came to recover the bodies, the Lakota and Cheyenne had already removed most of their dead from the field. The troops found most of Custer's dead stripped of their clothing, ritually mutilated, and in a state of decomposition, making identification of many impossible.[30] The soldiers identified the 7th Cavalry's dead as best as possible and hastily buried them where they fell.

Custer was found with shots to the left chest and left temple. Either wound would have been fatal, though he appeared to have bled from only the chest wound, meaning his head wound may have been delivered postmortem. Some Lakota oral histories assert that Custer committed suicide to avoid capture and subsequent torture, though this is usually discounted since the wounds were inconsistent with his known right-handedness. (Other native accounts note several soldiers committing suicide near the end of the battle.)[31] Custer's body was found near the top of Custer Hill, which also came to be known as "Last Stand Hill". There the United States erected a tall memorial obelisk inscribed with the names of the 7th Cavalry's casualties.[30]

Several days after the battle, Curley, Custer's Crow scout who had left Custer near Medicine Tail Coulee (a drainage which led to the river), recounted the battle, reporting that Custer had attacked the village after attempting to cross the river. He was driven back, retreating toward the hill where his body was found.[32] As the scenario seemed compatible with Custer's aggressive style of warfare and with evidence found on the ground, it became the basis of many popular accounts of the battle.

According to Pretty Shield, the wife of Goes-Ahead (another Crow scout for the 7th Cavalry), Custer was killed while crossing the river: "... and he died there, died in the water of the Little Bighorn, with Two-bodies, and the blue soldier carrying his flag".[33]: 136 In this account, Custer was allegedly killed by a Lakota called Big-nose.[33]: 141 However, in Chief Gall's version of events, as recounted to Lt. Edward Settle Godfrey, Custer did not attempt to ford the river and the nearest that he came to the river or village was his final position on the ridge.[34]: 380 Chief Gall's statements were corroborated by other Indians, notably the wife of Spotted Horn Bull.[34]: 379 Given that no bodies of men or horses were found anywhere near the ford, Godfrey himself concluded "that Custer did not go to the ford with any body of men".[34]: 380

Cheyenne oral tradition credits Buffalo Calf Road Woman with striking the blow that knocked Custer off his horse before he died.[35]

By the end of the day on 26 June 1876, the 7th Cavalry Regiment has been effectively destroyed as a fighting unit. Although MAJ Reno's and CPT Benteen's commands managed to make good their escape, 268 Cavalrymen and Indian scouts lay dead. Among the fallen was Custer's younger brother, Thomas Custer, in command of C Company. Other 7th Cavalry officers who were killed or wounded in action include;

- Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer, Regimental Commander

- 1st Lt. William W. Cooke, Adjutant

- Assistant Surgeon George Edwin Lord

- Acting Assistant Surgeon James Madison DeWolf

- 2nd Lt. Charles Varnum, Chief of Scouts (detached from A Company, wounded)

- 2nd Lt. Benjamin Hodgson, Adjutant to Major Reno

- Capt. Thomas Custer, C Company Commander

- 2nd Lt. Henry Moore Harrington, C Company

- 1st Lt. Algernon Smith, E Company Commander

- 2nd Lt. James G. Sturgis, E Company

- Capt. George Yates, F Company Commander

- 2nd Lt. William Reily, F Company

- 1st Lt. Donald McIntosh, G Company Commander

- Capt. Myles Keogh I Company Commander

- 1st Lt. James Porter, I Company

- 1st Lt. James Calhoun, L Company Commander

- 2nd Lt. John J. Crittenden, L Company

Nez Perce War

In 1877, one year after the 7th Cavalry's defeat at the Little Bighorn, the Nez Perce War began. The Nez Perce were a coalition of tribal bands led by several chiefs; Chief Joseph and Ollokot of the Wallowa band, White Bird of the Lamátta band, Toohoolhoolzote of the Pikunin band, and Looking Glass of the Alpowai band. Together, these bands refused to be relocated from their tribal lands to a reservation in Idaho, a violation of the 1855 Treaty of Walla Walla. When a US Army expedition loomed, the Nez Perce attempted to break out and flee to Canada to seek the aid of Sitting Bull, who had fled there after the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Battle of Canyon Creek

As the Army pursued the Indians through Idaho into Montana, elements of the 7th Cavalry joined the chase. Major Lewis Merrill and Captain Frederick Benteen, a veteran of the Little Bighorn, each led a battalion of the 7th. Merrill's Battalion consisted of Company F (CPT James M. Bell), Company I (CPT Henry J. Nowlan), and Company L (1LT John W. Wilkinson). Benteen's Battalion consisted of Company G (1LT George O. Wallace), Company H (2LT Ezra B. Fuller), and Company M (CPT Thomas H. French). In September 1877, these battalions were with COL Samuel D. Sturgis's column when they caught up to the Nez Perce raiding ranches up and down the Yellowstone River. The 7th Cavalry troopers were exhausted from their forced march and anticipated a rest after they crossed the Yellowstone River on the morning of 13 September, but Crow scouts reported the Nez Perce were moving up Canyon Creek six miles away.

Seeing an opportunity, Sturgis sent Major Merrill and his battalion ahead atop a long ridge to head off the Nez Perce traversing the shallow canyon below. Benteen's battalion followed, while Sturgis stationed himself with the rear guard. Merrill was halted on the ridge by a scattering of rifle shots from Nez Perce warriors. In the words of his civilian scout, Stanton G. Fisher, Merrill's battalion dismounted and deployed "instead of charging which they should have done."[36] According to Yellow Wolf, a single Nez Perce, Teeto Hoonod, held up the advance for a crucial ten minutes, firing 40 well-aimed shots at the cavalry from behind a rock.[37] The caution of the soldiers was perhaps due to the formidable reputation of the Nez Perce for military prowess and marksmanship. Gale-force winds impacted marksmanship, a factor explaining low casualties on both sides.[36]

When Sturgis arrived at the battleground, he perceived that his troops still had the possibility of capturing the Nez Perce horse herd. He sent Captain Benteen and his men on a swing to the left to plug the exits from the canyon and trap the women, children, and horses.[38] Merrill was told to advance into the canyon to threaten the rear of the Nez Perce column, but he was held up by an increasing number of Nez Perce warriors firing at long distance at his soldiers. He succeeded only in capturing a few horses. Benteen also ran into opposition and was unable to head off the horse herd, the Nez Perce occupying high ground and firing at the soldiers. A rearguard of the Nez Perce held off the soldiers until nightfall. Most of their horse herd and their women and children reached the plains and continued north.[38] Three Troopers were killed and eleven wounded (one mortally) when the shooting stopped. Martha Jane Cannary, better known as "Calamity Jane," accompanied the wounded by boat down the Yellowstone River as a nurse.[38] According to Yellow Wolf, three Nez Perce were killed and three wounded.

Despite pursuing the band for two days (traveling 37 miles the first day alone), the weary 7th was unable to catch up to their quarry. They awaited reinforcements and supplies on the Musselshell River for two days and continued on once they arrived.

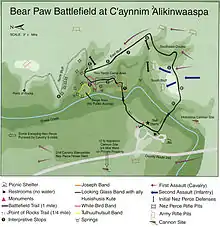

Battle of Bear Paw

In late September, the US Army expedition finally caught up with Chief Joseph's band of Nez Perce. Under General Oliver Otis Howard and Colonel Nelson A. Miles the expedition consisted of a Battalion of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment, a Battalion of the 5th Infantry Regiment, Cheyenne and Lakota scouts (many of which had fought against Custer at the Little Bighorn a year earlier), and a Battalion of the 7th Cavalry Regiment. The 7th Cavalry element was commanded by Captain Owen Hale and consisted of Company A (CPT Myles Moylan), Company D (CPT Edward Settle Godfrey), and Company K (under CPT Owen Hale himself). Captains Moylan and Godfrey were both survivors of the Battle of Little Bighorn, as were many of their men, making them a battle-hardened outfit.

On 30 September 1877, the Battle of Bear Paw began. Miles' Indian scouts located the Nez Perce camp and the Cavalry were hastily deployed. At 9:15 AM, while still about six miles from the camp, the cavalry started at a trot, organized as follows: the 30 Cheyenne and Lakota scouts led the way, followed by 160 Troopers of the 2nd Cavalry. The 2nd Cavalry was ordered to charge into the Nez Perce camp. 110 Troopers of the 7th Cavalry followed the 2nd as support on the charge into the camp. 145 Soldiers of the 5th Infantry, mounted on horses, followed as a reserve with a Hotchkiss gun and the pack train. Miles rode with the 7th Cavalry.[39]

The Nez Perce camp was alerted by sentries to the US charge and quickly began to prepare. Women and children rushed north towards Canada, some Nez Perce began gathering the horse herd, some began packing up the camp, and the warriors prepared to fight. Rather than rushing the camp directly, the Cheyenne scouts veered off to the Nez Perce horse herd for plunder, and the 2nd Cavalry followed them. However, the 7th under CPT Hale followed the plan and charged into the enemy camp. As they approached, a group of Nez Perce rose up from a coulee and opened fire, killing and wounding several soldiers, forcing them to fall back. Miles ordered two of the three companies in the 7th Cavalry to dismount and quickly brought up the mounted infantry, the 5th, to join them in the firing line. Hale's Company K meanwhile had become separated from the main force and was also taking casualties. By 3:00 PM, Miles had his entire force organized and on the battlefield and he occupied the higher ground. The Nez Perce were surrounded and had lost all their horses. Miles ordered a charge on the Nez Perce positions with the 7th Cavalry and one company of the infantry, but it was beaten back with heavy casualties.

At nightfall on 30 September, Miles' casualties amounted to 18 dead and 48 wounded, including two wounded Indian scouts. The 7th Cavalry took the heaviest losses. Its 110 men suffered 16 dead and 29 wounded, two of them mortally. The Nez Perce had 22 men killed, including three leaders: Joseph's brother Ollokot, Toohoolhoolzote, and Poker Joe – the last killed by a Nez Perce sharpshooter who mistook him for a Cheyenne.[40] Several Nez Perce women and children had also been killed. Miles later said of the battle that "the fight was the most fierce of any Indian engagement I have ever been in....The whole Nez Perce movement is unequalled in the history of Indian warfare."[41]

The end of the pitched battle marked the beginning of a long siege while negotiations commenced. As the year 1877 began falling to winter, the cold siege ended when Chief Joseph surrendered, famously saying

Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before I have in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Tu-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men [Ollokot] is dead. It is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are – perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.

Crow War

In 1887, the state of Montana was host to a minor war between the Crow and the Blackfoot Indians where both tribes raided each other's reservations in order to steal horses. In late spring, a Blackfoot war party made off with several Crow horses, prompting Crow war-leader Sword Bearer to lead a retaliatory raid against his Chief's decision. The raid stepped off in September, and the war party consisted of teenage braves eager to prove themselves in battle. During the raid, a number of Blackfoot braves were killed and the Crow recovered their horses without loss, but when they returned to the reservation, on 30 September, Sword Bearer made the mistake of showing off his victory to the Indian agent, Henry E. Williamson, who was known for being disliked by the native population. In what was called the Crow Incident, Sword Bearer and his men circled around Williamson's home and fired into the air and at the ground near Williamson's feet, prompting him to wire the Army at Fort Custer for help. When the Army force arrived, their cannon failed to fire, allowing Sword Bearer and his men to flee into the Big Horn Mountains.

An expedition under Brigadier General Thomas H. Ruger and Colonel Nathan Dudley was sent to occupy the reservation to hamper Sword Bearer's recruitment. The force included five troops of the 1st Cavalry Regiment, one Company from the 3rd Infantry Regiment, and A Company from the 7th Cavalry Regiment under the command of Captain Myles Moylan, a veteran of the Battle of Little Bighorn and a recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Battle of Bear Paw. Heading into the mountains on 4 November 1887, the expedition caught up with the Crow band camped on the Little Bighorn River, some three miles from the site of Custer's Last Stand (some of Sword Bearer's followers were veterans of the battle). Company A, 7th Cavalry was posted on the right flank of the US line at the time of the battle. Sword Bearer charged with 150 mounted warriors but was repulsed and forced to retreat to a series of rifle pits dug into a wooded area near the river.

The American cavalry then counterattacked. In the words of Private Morris; "The cavalry charged and took a volley from the Indian camp. At 200 yards we leaped from our horses and flattened out behind clumps of sagebrush. We traded shots for a while, until two Hotchkiss field guns on the hill began dumping two-inch into the Indian camp. That broke them." During the fighting, Sword Bearer attempted to encourage his men by riding out in front of the soldiers but he was struck by rifle fire and fell to the ground wounded. Eventually some of the Crow began to surrender but Sword Bearer and the others remained in the mountains, only to surrender later on to the Crow police. It was during the march out of the Big Horn that one of the policemen shot Sword Bearer in the head, killing him instantly and ending the war. One soldier was killed and two others were wounded during what is now called the Battle of Crow Agency. Seven Crow warriors were killed and nine were wounded. An additional nine men were also taken prisoner and all of those who had not taken part in the battle were taken to Fort Snelling, Minnesota. The expedition returned to Fort Custer on 13 November.[42][43][44]

Ghost Dance War

In 1890, a great phenomena spread among the Indian tribes of the Great Plains. It was called the Ghost Dance, and it promised its believers that the white man would be thrown from the American continent, and the bison herds would be returned to their former range and size. White settlers near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation were alarmed by the number of Ghost Dance performers, which included the famous Lakota Chief Sitting Bull. James McLaughlin, the Standing Rock Indian Agent, requested military aid to stop what he saw as the beginnings to a dangerous uprising. Military leaders wanted to use Buffalo Bill Cody, a friend of Sitting Bull's, as an intermediary to avoid violence, but were overruled by McLaughlin who sent in the Indian agency police to arrest Sitting Bull.

On 15 December 1890, forty Indian Police arrived at Sitting Bull's house to arrest him. When he refused, the police moved in, prompting Catch-the-Bear, a Lakota, to fire his rifle, hitting LT Bullhead. LT Bullhead responded by shooting Sitting Bull in the chest, and Policeman Red Tomahawk subsequently shot the Chief in the head, killing him. Fearing reprisals for the incident, 200 of Sitting Bull's Hunkpapa fled to join Chief Spotted Elk at the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation. Spotted Elk, in turn, fled to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation to join Chief Red Cloud.

A detachment of the 7th Cavalry Regiment under Major Samuel Whitside was sent to maintain order, and on 28 December they met with Red Cloud's band southwest of Porcupine Butte as they moved to Pine Ridge. John Shangreau, a scout and interpreter who was half Sioux, advised the troopers not to disarm the Indians immediately, as it would lead to violence. The troopers escorted the Native Americans about five miles westward to Wounded Knee Creek where they told them to make camp. Later that evening, Colonel James W. Forsyth and the rest of the 7th Cavalry arrived, bringing the number of troopers at Wounded Knee to 500.[45]

Wounded Knee

At daybreak on 29 December 1890, Forsyth ordered the surrender of weapons and the immediate removal of the Lakota from the "zone of military operations" to awaiting trains. A search of the camp confiscated 38 rifles, and more rifles were taken as the soldiers searched the Indians. None of the old men were found to be armed. A medicine man named Yellow Bird allegedly harangued the young men who were becoming agitated by the search, and the tension spread to the soldiers.[46] Yellow Bird began to perform the Ghost Dance, telling the Lakota that their "ghost shirts" were bulletproof. As tensions mounted, Black Coyote refused to give up his rifle; he spoke no English and was deaf, and had not understood the order. Another Indian said: "Black Coyote is deaf," and when the soldier persisted, he said, "Stop. He cannot hear your orders." At that moment, two soldiers seized Black Coyote from behind, and (allegedly) in the struggle, his rifle discharged. At the same moment, Yellow Bird threw some dust into the air, and approximately five young Lakota men with concealed weapons threw aside their blankets and fired their rifles at Troop K of the 7th. After this initial exchange, the firing became indiscriminate.[47]

At first all firing was at close range; half the Indian men were killed or wounded before they had a chance to get off any shots. Some of the Indians grabbed rifles from the piles of confiscated weapons and opened fire on the soldiers. With no cover, and with many of the Indians unarmed, this lasted a few minutes at most. While the Indian warriors and soldiers were shooting at close range, other soldiers (from Battery E, 1st Artillery) used the Hotchkiss guns against the tipi camp full of women and children. It is believed that many of the soldiers were victims of friendly fire from their own Hotchkiss guns. The Indian women and children fled the camp, seeking shelter in a nearby ravine from the crossfire.[48] The officers had lost all control of their men. Some of the soldiers fanned out and finished off the wounded. Others leaped onto their horses and pursued the Natives (men, women, and children), in some cases for miles across the prairies. In less than an hour, at least 150 Lakota had been killed and 50 wounded. Historian Dee Brown, in Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, mentions an estimate of 300[49] of the original 350 having been killed or wounded and that the soldiers loaded 51 survivors (4 men and 47 women and children) onto wagons and took them to the Pine Ridge Reservation.[50] Army casualties numbered 25 dead and 39 wounded.

Drexel Mission Fight

On 30 December 1890, the day after Wounded Knee, COL Forsyth and 8 Troops of the 7th Cavalry and one platoon of Artillery (the same units that had been engaged at Wounded Knee), conducted a reconnaissance to see if the nearby Catholic Mission had been torched by the Indians. In what became known as the Drexel Mission Fight, the 7th Cavalry was ambushed in a valley by Brulé Lakota under Chief Two Strike from the Rosebud Indian Reservation. After exchanging fire with the Indians, the shots were heard by the nearby 9th Cavalry (Buffalo Soldiers) under Major Guy Vernor Henry who rode to the rescue. The Indians were driven off. The 7th Cavalry suffered 2 killed and 7 wounded;

- 1LT James D. Mann – Troop K, DOW

- PVT Dominick Franceshetti – Troop G, KIA

- PVT Marrion C. Hillock – Troop B, WIA

- PVT William S. Kirkpatrick – Troop B, WIA

- PVT Peter Claussen – Troop C, WIA

- PVT William Kern – Troop D, WIA

- Farrier Richard J. Nolan – Troop I, WIA

- 1SG Theodore Ragnor – Troop K, WIA

Medal of Honor recipients

A total of 45 men earned the Medal of Honor while serving with the 7th Cavalry during the American Indian Wars: 24 for actions during the Battle of the Little Bighorn, two during the Battle of Bear Paw, 17 for being involved in the Wounded Knee Massacre or an engagement at White Clay Creek the next day, and two during other actions against the Sioux in December 1890.[51]

|

|

Overseas and the Mexican border

From 1895 until 1899, the regiment served in New Mexico (Fort Bayard) and Oklahoma (Ft. Sill), then overseas in Cuba (Camp Columbia) from 1899 to 1902. An enlisted trooper with the Seventh Cavalry, "B" Company, from May 1896 until March 1897 at Fort Grant Arizona Territory was author Edgar Rice Burroughs.

The regiment served in the Philippines during the Philippine–American War from 1904 through 1907, with a second tour from 1911 through 1915. Here they conducted counter-insurgency operations against Filipino guerrillas in the jungles and rural areas of the islands.

Border war

Back in the United States, the regiment was again stationed in the southwest, in Arizona (Camp Harvey J. Jones), where it patrolled the U.S.-Mexico border and later was part of the Mexican Punitive Expedition of 1916 to 1917. During this expedition, the 7th Cavalry executed what is regarded as America's "last true Cavalry charge" at the Battle of Guerrero.[52] Colonel George A. Dodd, commanding a force of 370 from the 7th Cavalry, led his Troopers into the Mexican State of Chihuahua in pursuit of Pancho Villa. After riding 400 miles in 14 days, Dodd's exhausted Troopers finally caught up with Villa's force in the town of Guerrero on 29 March 1916.

The 7th Cavalry was low on rations, and had to fight a battle against a well defended town. According to varying sources, there were between 200 and 500 Villistas at Guerrero, spread out across the town, and for the first couple of hours after the 7th Cavalry's arrival, Dodd had his men attempt to ascertain the number of enemy forces. It was not until 8:00 am that the order to attack was given. Dodd divided his command into three contingents with instructions to charge and surround the town in order to cut off the Villistas's avenue of escape. When the Americans charged, fighting erupted at three points. After the charge the Americans dismounted to fight the Mexicans on foot. Guerrero was flanked by mountains on two sides which made it difficult to surround the town and the Villistas used them for cover. There were also not enough cavalrymen to cover all of the escape routes so the majority of the Mexicans got away, including Pancho Villa. Part of the Villista army mounted up and retreated east through a valley. They were pursued by some of the American cavalrymen in a ten-mile running engagement. Another force of Mexicans calmly rode out of Guerrero, pretending to be Carrancistas by displaying a Mexican national flag, this group went unmolested by the 7th Cavalry. Villa lost his friend, General Elicio Hernandez, and fifty-five others killed in the battle and another thirty-five wounded. The Americans suffered only five wounded during a five-hour battle. Colonel Dodd and his men also captured thirty-six horses and mules, two machine guns, many small arms and some war supplies. Several condemned Carrancista prisoners were liberated.

Initially the Battle of Guerrero was thought to be a great opening success in the campaign but it later proved to be a disappointment as it would be the closest they came to capturing Villa in battle. However, the battle was considered the "most successful single engagement of Pershing's Punitive Expedition." After the retreat the Villista army dispersed and for the next three months they no longer posed a significant threat to the United States military. Villa himself hid out in the hills while his knee healed. One day, not long after the battle, Villa was camped at the end of a valley and watched a troop of Pershing's cavalrymen ride by. Villa heard them singing "It's a Long Way to Tipperary," this would be the last time Americans got so close to the rebel. News of the victory was widely circulated in the United States, prompting the Senate's approval of Colonel Dodd's promotion to brigadier general.

In December 1917, eight months after the American entry into World War I, the 7th Cavalry was assigned to the 15th Cavalry Division, an on-paper organization designed for service in France during World War I that was never more than a simple headquarters. This was because no significant role emerged for mounted troops on the Western Front during the 19 months between the entry of the United States into the war and the Armistice with Germany on November 11, 1918.[53] The 7th Cavalry was released from this assignment in May 1918.

On 15 June 1919, Pancho Villa fought his last battle with the Americans. At the Battle of Ciudad Juárez, Villista and Carrancista forces engaged in combat in Ciudad Juárez just south of El Paso, Texas across the Rio Grande. The 7th Cavalry was temporarily at Fort Bliss and responded to the battle when Villista snipers killed and wounded US Soldiers of the 82nd Field Artillery Regiment. The 12th Infantry Regiment, the 82nd Field Artillery, the 5th Cavalry Regiment, and the 7th Cavalry Regiment quickly crossed the Santa Fe Bridge into Mexico to deal with the threat. Advancing towards the enemy, the 7th Cavalry covered the main body's flank, and then, under the protection of artillery fire, charged the Villistas and routed them.

Interwar period

On 13 September 1921, 7th Cavalry Regiment was assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division, which assignment was maintained until 1957. The division and its 2nd Cavalry Brigade was garrisoned at Fort Bliss, Texas, while the 1st Cavalry Brigade was garrisoned at Douglas, Arizona. Additional garrison points were used as well.

The 7th Cavalry Regiment continued to train as horse cavalry right up to the American entry into World War II, including participation in several training maneuvers at the Louisiana Maneuver Area on 26 April – 28 May 1940; 12–22 August 1940; and 8 August – 4 October 1941.

World War II

On 7 December 1941, the Empire of Japan attacked the US fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor, thrusting the United States into World War II, which had already been raging since 1939. The Troopers of the 1st Cavalry Division readied their horses, their equipment, and themselves for the coming war, and were finally alerted for deployment in 1943. Despite being a mounted Cavalry unit since 1866, the 7th Cavalry left its mounts behind in Texas as they left for war; the age of the horse-cavalry was over. The newly dismounted 7th Cavalry Regiment was sent to fight in the Pacific Theater of Operations and the last units left Fort Bliss for Camp Stoneman, CA in June 1943.[2] On 3 July, the 7th Cavalry boarded the SS Monterey and the SS George Washington bound for Australia. The regiment arrived on 26 July, and was posted to Camp Strathpine, Queensland where they underwent six months of intensive jungle warfare training, and conducted amphibious assault training at nearby Moreton Bay.[2]

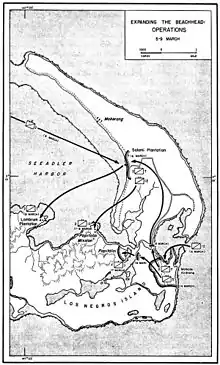

Admiralty Islands campaign

In January 1944, the 7th Cavalry sailed for Oro Bay on the island of New Guinea. Despite the ongoing New Guinea Campaign, the 7th Cavalry was held in reserve and was organized into "Task Force Brewer" for another mission. On 27 February, TF Brewer embarked from Cape Sudest under the command of Brigadier General William C. Chase. Their objective was the remote Los Negros Island in the Admiralty Islands which had an important airfield occupied by the Japanese. The 5th Cavalry Regiment landed on 29 February and began the invasion.

The morning of 4 March saw the arrival of the 2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry, which relieved the 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry. The next day Major General Innis P. Swift, the commander of the 1st Cavalry Division, arrived aboard Bush and assumed command. He ordered the 2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry to attack across the native skidway. The 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry therefore went back into the line to relieve them. While the relief was taking place, the Japanese launched a daylight attack. This was repulsed by the cavalrymen, with the help of artillery and mortar fire, but the American attack was delayed until late afternoon. It then ran into a Japanese minefield and by dawn the advance had only reached as far as the skidway.[54] On the morning of 6 March, another convoy arrived at Hyane Harbour: five LSTs, each towing an LCM, with the 12th Cavalry and other units and equipment including five Landing Vehicles Tracked (LVTs) of the 592nd EBSR, three M3 light tanks of the 603rd Tank Company, and twelve 105mm howitzers of the 271st Field Artillery Battalion.[55] The 12th Cavalry was ordered to follow the 2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry in its advance to the north, and to capture the Salami Plantation. The road to Salami was little more than a muddy track in which vehicles soon became bogged. The Japanese also obstructed the route with ditches, felled trees, snipers, and booby traps.[56] Despite incessant rain and suicidal Japanese counterattacks, the 7th Cavalry captured their objectives and mop-up operations were being conducted from 10 to 11 March. Manus Island, to the west, was the next target.

The main landing was to be at Lugos Mission, but General Swift postponed the landing there and ordered the 2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry to capture Hauwei.[57] The landing was covered by the destroyers Arunta, Bush, Stockton and Thorn;[58] a pair of rocket-firing LCVPs and the LCM (flak), which fired 168 4.5-inch (114 mm) rockets; the guns of the 61st Field Artillery Battalion on Los Negros;[59] and six Kittyhawks of No. 76 Squadron dropped 500-pound (230 kg) bombs.[60] The assault was made from three cargo-carrying LVTs. To save wear and tear, they were towed across Seeadler Harbour by LCMs and cut loose for the final run in to shore.[61] The cavalrymen found well constructed and sited bunkers with interlocking fields of fire covering all approaches, and deadly accurate snipers. The next morning an LCM brought over a medium tank, for which the Japanese had no answer, and the cavalrymen were able to overcome the defenders at a cost of eight killed and 46 wounded; 43 dead Japanese naval personnel were counted.

The 8th Cavalry Regiment began the main assault on Manus on 15 March and attacked the important Lorengau Airfield on 17 March. After initially quickly overrunning the enemy positions, the cavalry resumed its advance, and occupied a ridge overlooking the airstrip without opposition. In the meantime, the 7th Cavalry had been landed at Lugos from the LST on its second trip and took over the defense of the area, freeing the 2nd Squadron, 8th Cavalry to join the attack on Lorengau. The first attempt to capture the airstrip was checked by an enemy bunker complex. A second attempt on 17 March, reinforced by the 1st Squadron, 7th Cavalry and tanks, made good progress. The advance then resumed, with Lorengau itself falling on 18 March.

Although there had been plenty of fighting, the main Japanese force on Manus had not been located. Advancing inland towards Rossum, the 7th Cavalry found it on 20 March. Six days of fighting around Rossum were required before the 7th and 8th Cavalry reduced the entrenched Japanese positions there. The Japanese bunkers, actually log and earth pillboxes, proved resistant to artillery fire.[62] These weary Troopers were relieved by the 7th Cavalry on 18 March. That day, the 7th Cavalry attacked, and drove the enemy out of Lorengau Village.

The Admiralty Islands campaign ended on 18 May 1944 with the islands and airfields secured and 3,317 Japanese dead. The 7th Cavalry Regiment suffered 43 killed in action, 17 wounded, and 7 dead from non-battle injuries. Having faced down suicidal Japanese counterattacks and a stubborn defense in the rainy jungles of the Southwest Pacific, the 7th Cavalry Troopers were now veterans.[2]

Battle of Leyte

After a period of 5 months in rehabilitation and extensive combat training, the 7th Cavalry Regiment received instructions on 25 September 1944 to prepare for future combat operations. On 20 October, the regiment began the assault of Leyte Island.

The Battle of Leyte began when the first waves of the 7th Cavalry Regiment stormed ashore at White Beach at 1000, H-Hour, and were met with small arms and machine gun fire. 1st Squadron-7th Cavalry Regiment (1-7 Cavalry) landed on the right flank and was to attack north into the Cataisan Peninsula to capture Tacloban Aerodrome. To the left, 2-7 Cavalry was to attack inland, capture San Jose, and seize a beachhead line west of Highway 1. They were met with slight opposition, and within the first 15 minutes, 2-7 Cavalry knocked out two Japanese defensive pillboxes firing into the landing zone. After a house-to-house assault, San Jose was captured by 1230. 2-7 Cavalry's largest obstacle was the terrain. "Directly beyond the landing beaches the troops ran into a man-enveloping swamp. All along the line, men cursed as they wallowed toward their objective in mud of arm-pit depth. This unexpectedly tough obstacle however, failed to deter their dogged advance.[63]" By 1545 2-7 Cavalry had crossed Highway No 1. Meanwhile, 1-7 Cavalry, under the command of Major Leonard Smith, had secured the Cataisan Peninsula and the Tacloban Airfield with the aid of the 44th Tank Battalion. All the 7th Cavalry's A-Day objectives had been seized before nightfall.

The following day, 21 October 1944, saw 7th Cavalry begin the attack on Tacloban. At 0800, the 1st and 2nd Squadrons advanced abreast toward the city. 1-7 Cavalry entered the city and were overwhelmed by crowds of exuberant Filipinos giving them gifts of eggs and fruit. 2-7 Cavalry, meanwhile, was halted by a force of 200 Japanese entrenched in prepared fighting positions.[64] The Regimental Weapons Troop and Anti-Tank Platoon arrived to break the stalemate but were quickly pinned down by machine gun fire from a bunker as well. PFC Kenneth W. Grove, an ammunition carrier, singlehandedly cut through the jungle, charged the bunker and killed the weapons crew, and allowed the advance to resume. By the end of 22 October the capital of Leyte and its hill defenses were securely in American hands. The 7th Cavalry was one day ahead of schedule, a fact partly explained by the unexpectedly light resistance of the Japanese and partly by the vigor of the 7th Cavalry's advance[65]

On 23 October, the 7th was relieved by the 8th Cavalry and prepared to undertake operations to secure the San Juanico Strait across from the island of Samar. On 24 October, 1-7 Cavalry landed at Babatngon at 1330 and sent out patrols to secure the beachhead. The landing was unopposed, and 1-7 Cavalry made several other over-water movements to secure the area, making the most of the scant Japanese resistance. By 27 October, 7th Cavalry (minus 1st Squadron) was in reserve.[64] 1-7 Cavalry, in Babatngon, was ordered to secure the Barugo and Carigara area. Troop C, under 1LT Tower W. Greenbowe, advanced on 28 October without incident, but received fire from Carigara. In the ensuing firefight, C Troop eliminated 75 enemies at the cost of 3 killed, 9 wounded, and 1 missing (the mutilated body of the missing man was found later)[64] before withdrawing to Barugo, where it was joined by the rest of the Squadron on 29 October for an assault on Carigara. They attacked across the Canomontag River by using 2 native canoes, and occupied Carigara by 1200 with no resistance.[64]

After remaining in a reserve role, 2-7 Cavalry relieved elements of the 12th Cavalry operating in the central mountain range of the island. Between 11 and 14 December, they continually assaulted a series of well-defended ridges and hills and only were able to wrest control over them by calling in over 5,000 rounds of artillery support. The 1st Cavalry Division continued to push west toward the coast through the mountainous and dense jungle interior of the island. On the morning of 23 December 1944, 1st Squadron, 7th Cavalry assault units pushed across Highway 2 and set up night positions on line with the other divisional units. They pushed off for the attack the next morning meeting only scattered resistance. By 29 December, 7th Cavalry units reached the west coast, north of the village of Tibur, and drove north, capturing the town of Villaba, and killing 35 Japanese there.[64] On 31 December, the Japanese launched four counterattacks on the 7th Cavalry, each starting with a bugle call. The first occurred at 0230 and the last one was at dawn. An estimated 500 enemy attacked the positions, but they were driven off by the stalwart defenders and by American artillery superiority. 77th Infantry Division elements began relieving the 7th Cavalry later that day.[64] Leyte was soon declared secure, despite the large number of Japanese soldiers remaining hidden in the thick jungle of the island's interior, and elements of the 7th Cavalry were kept busy by conducting mop-up missions and patrols until their next big operation.

Battle of Luzon

For the forces of General MacArthur's Southwest Pacific Area the reconquest of Luzon and the Southern Philippines was the climax of the Pacific war. Viewed from the aspect of commitment of U.S. Army ground forces, the Luzon Campaign (including the seizure of Mindoro and the central Visayan Islands) was exceeded in size during World War II only by the drive across northern France. The Luzon Campaign differed from others of the Pacific war in that it alone provided opportunity for the employment of mass and maneuver on a scale even approaching that common to the European and Mediterranean theaters.[66]

The initial Army units in the invasion had landed on 9 January and secured a beachhead, but GEN MacArthur needed more forces on the island to begin his drive to Manila. Despite not receiving adequate rest and replacements from the Battle of Leyte, the 1st Cavalry Division was sent ahead to take part in the Battle of Luzon and landed in Lingayen Gulf on 27 January 1945.[67] The 7th Cavalry quickly moved inland toward Guimba, but as A Troop passed through Labit, they were attacked by a Japanese ambush unit. Technical Sergeant John B. Duncan, of Los Angeles, CA, was cited for his courageous and determined effort to drive the attackers back. He succeeded in doing so, but was mortally wounded. MacArthur ordered that the 1st Cavalry Division assemble three "Flying Columns" for the drive on Manila. The 7th Cavalry was tasked with providing security for them, and air cover on the left flank was provided by the Marine Aircraft Groups 24 and 32 of the 1st Marine Air Wing.[68] As elements of the 8th Cavalry swung south, the 7th Cavalry advanced by foot and kept the Japanese occupied while their counterparts broke through. On 4 February 1945, LTC Boyd L. Branson, the Regimental operation officer from San Mateo, CA, earned the Silver Star by voluntarily leading the advance units over more than 40 miles of un-reconnoitered, enemy-held terrain. While the rest of the Division was fighting in Manila, the 7th Cavalry engaged the enemy near the Novaliches watershed east of the city to prevent their reinforcement. On 20 February, they handed over their positions to elements of the 6th Infantry Division and moved south to begin the attack on the Shimbu Line.[63]

Attacking eastward on the 20th during the onset of the Battle of Wawa Dam, 2-7 Cavalry spearheaded deep into the Japanese line but were quickly fired upon by a heavy barrage of artillery.[63] Drawing on their experiences from the Admiralties and Leyte for attacking entrenched enemy positions in mountainous jungle terrain, the Troopers advanced and destroyed the pillboxes and mortar positions. By 25 February, the 7th Cavalry was 2 kilometers from their objective at Antipolo. The advance continued, and on 4 March, the 7th Cavalry was hit by a strong Japanese counterattack that managed to destroy two of the American's supporting tanks before it was defeated.[63] The battle for Antipolo was marked by bitter struggle in unforgiving terrain, and the 1st Cavalry Division was relieved by the 43rd Infantry Division on 12 March after finally capturing the ruined village. Out of the 92 Silver Stars awarded to men of the 1st Cavalry Division in their drive to Antipolo, the largest share went to men of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, with 41 being awarded.[63] PFC Calvin T. Lewis, of Glasgow, KY, B Troop 7th Cavalry, was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for heroism in defeating an enemy bunker. After his platoon was halted by accurate machine gun fire from a concealed bunker, he volunteered to go find it. Wielding a Browning Automatic Rifle, he located the position and poured heavy and accurate fire through the bunker's opening. After pinning the enemy down, he moved up and fired into the opening from close range, but was mortally wounded in doing so. Despite his wounds he continued to engage the enemy until all were killed.[63]

After being relieved in their sector on 20 April, the 7th Cavalry prepared for another mission; the capture of Infanta on the east coast of Luzon, which was held by 9,000 troops of the Manila Naval Defense Forces of the Japanese Imperial Navy under Capt. Takesue Furuse who were able to escape the encirclement by the 11th Airborne Division at Fort McKinley mid-February.[69] On 6 May 1945 the 7th Cavalry began moving south into the Santa Maria Valley toward Lamon Bay along Route 455. Along the hairpin curves of the highway, they encountered tough Japanese resistance at the Kapatalin Sawmill. For several days the advance was stalled as patrols reconnoitered the position and pinpointed targets for US Army Air Corps planes. They overran the enemy by mid-afternoon of 9 May. They had killed 350 Japanese for the loss of 4 KIA and 17 WIA. They reached Lamon Bay on 13 May.[70] Sweeping aside Japanese resistance on their march to the coast, the 7th Cavalry Troopers occasionally encountered determined defenders, and the fighting along the advance was characterized by small unit action. On 18 May, A Troop was moving to Real when the lead platoon was pinned down by enemy rifle and machine gun fire. Thinking quickly, Lieutenant Joe D. Crane of Athens, TX led his platoon in a flanking maneuver and annihilated the enemy force, saving his comrades. Near Gumian on 22 May, D Troop was attacked by a large force of 150 Japanese with machine guns, mortars, grenades, and rifles.[70] The foliage was thick enough to conceal the enemy, allowing them to come within ten yards of the Cavalrymen's positions before being detected. LT Charles E. Paul of Camden, AR moved to an observation post in the thick of the fighting and called in close and accurate mortar fire, driving the enemy away, and earning the Silver Star for his actions. Accompanied by Philippines guerrillas, the 7th Cavalry captured Infanta on 25 May and soon after secured the surrounding rice-fields. They remained here for some time patrolling the area for Japanese holdouts.[70] By 1 June 1945, most of southern Luzon was in American hands, but there were still determined Japanese forces in the area. On 2 June, 30 Japanese attacked F Troop's positions just before dawn broke and the Americans were forced to fight in hand-to-hand combat. SGT Jessie Riddell of Irvine, KY earned his second Silver Star in this attack when he saw one of his Troopers in a death struggle with a Japanese officer wielding a samurai sword. SGT Riddell ran to his aid, shooting 3 attackers on the way, and killed the enemy officer before he could kill the American.[70]

Continuing their patrolling of southern Luzon, a patrol from B Troop ran into an unexpectedly heavy ambush on 19 June 1945. Despite the shock of the ambush, PVT Bernis L. Stringer of Visalia, CA, the patrol's BAR-man, ran forward, killing one Japanese and wounding another. He then reloaded in plain sight of the last enemy soldier before dispatching him too. PVT Stringer lost his life soon after in the closing days of the campaign. The Battle of Luzon was officially declared over on 30 June 1945 but scattered Japanese resistance remained.[70] The battle was the longest the 7th Cavalry had fought in World War II, and it would be their last. After pulling out of the combat zone on 4 July, The regiment began to rest and refit as it prepared for the inevitable invasion of the main Japanese islands. On 20 July, the 7th Cavalry again reorganized—this time entirely under Infantry Tables of Organization & Equipment, but still designated as a Cavalry Regiment, in order to bring it up to the full strength of a 1945 Army infantry regiment. Thankfully for the men of the 7th Cavalry, the invasion was terminated after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced the Japanese to surrender. 7th Cavalry Regiment was at Lucena, Tayabas (now. Quezon) in the Philippines until 2 September 1945, when it was moved to Japan to start occupation duty.

Occupation of Japan

On 13 August 1945, the 7th Cavalry was alerted that it would accompany General Douglas MacArthur to Tokyo and would be part of the Eighth Army's occupation force. On 2 September, the 7th Cavalry landed in Yokohama and began setting up a base of operation. On 8 September, the 1st Cavalry Division sent a convoy under Major General William C. Chase from Hara-Machida to Tokyo to occupy the city. This convoy was made up of one combat veteran from every Troop in the division, and it marched through Hachiōji, Fuchū, and Chōfu before reaching Tokyo; this convoy of the 1st Cavalry Division, with many veterans of the 7th Cavalry Regiment in the ranks, became the first Allied unit to enter the city.[2] The 7th Cavalry set its headquarters at the Japanese Imperial Merchant Marine Academy and were assigned to guard the US embassy and GEN MacArthur's residence. For five years they remained in Tokyo. On 25 March 1949, the 7th Cavalry was reorganized under a new table of organization, and its Troops were renamed Companies as in a standard infantry division.[2]

Korean War

When World War II ended, the communist Soviet Union and the countries of the Soviet bloc and the United States and its allies became locked in an ideological Cold War. They vied for power across the world using proxy states, but this tension boiled over in the Korean Peninsula. On 25 June 1950, the communist Democratic People's Republic of Korea crossed the 38th parallel and invaded the democratic Republic of Korea. Their military overwhelmed that of their southern neighbors and North Korean tanks were in Seoul within two days. The United States decided to intervene in favor of South Korea and quickly sent in troops with the promise that more were en route. On 18 July 1950, the 1st Cavalry Division's 5th and 8th Cavalry Regiments landed at Pohang-dong, 80 miles north of Pusan, in the war's first amphibious landing.[2] The 7th Cavalry landed at Pohang-dong on July 22.[71]: 196

The 7th Cavalry, under the command of Colonel Cecil W. Nist, was the 8th Army reserve at Pohang, but when the 5th Cavalry to the north was attacked in great force, the 7th moved up to reinforce them on 25 July.[71]: 203 Between 26 and 29 July, 7th Cavalry troopers were dug in astride the main highway 100 miles southeast of Seoul, but were unprepared for the waves of refugees fleeing south. Commanders feared the refugee columns might harbor North Korean infiltrators, and orders came down to stop refugee movements, with gunfire if necessary.[72]: 81 The troopers and officers of 2-7 Cavalry opened fire on innocent civilians, mostly women and children, in the No Gun Ri massacre. In 2005, a South Korean government inquest committee certified the names of 150 No Gun Ri dead, 13 missing, and 55 wounded, including some who later died of their wounds. It said reports were not filed on many other victims.[73]: 247–249, 278, 328 Survivors claim the number of dead was closer to 400.[74]

During the next few days a defensive line was formed at Hwanggan with the 7th Cavalry moving east and the 5th Cavalry replacing elements of the 25th Infantry Division.[2] On 1 August, the 1st Cavalry Division was ordered to set up a defensive position near Kumchon on the rail route from Taegu to Pusan. For more than 50 days between late July and mid September 1950, 7th Cavalry Troopers and UN Soldiers performed the bloody task of holding on the vital Pusan Perimeter.[2] At dawn on 9 August, North Korea hurled five divisions against the American lines along the Naktong River near Taegu and managed to gain some high ground. Major General Hobart R. Gay, commander of the 1st Cavalry Division, withheld counterattacking until he had more information, but soon learned that 750 Korean People's Army (KPA) troops had occupied Hill 268, soon to be known as "Triangulation Hill. At about 09:30, General Gay ordered 1-7 Cavalry to counter the KPA penetration. The Battalion moved from its bivouac area just outside Taegu, accompanied by five tanks of A Company, 71st Heavy Tank Battalion. This motorized force proceeded to the foot of Hill 268. Meanwhile, the 61st Field Artillery Battalion shelled the hill heavily.[75]"However, 1st Battalion-7th Cavalry Regiment counterattacked their flanks at 0930 that day, and managed to seize Hill 268, "Trianglation Hill", and killed 400 enemy. The morning of 10 August, a combined tank and infantry attack next reached the crest of the Triangulation Hill without much trouble, and this battle was over by about 16:00. US artillery and mortar fire was now shifted westward, and this cut off the KPA retreat. White phosphorus shells fired from the 61st Field Artillery Battalion caught KPA troops in a village while they attempted to retreat, and they were then routed by US infantry, suffering over 200 killed. That evening the 1-7 Cavalry, returned to the serve as the division reserve, and elements of the 5th Cavalry finished securing Hill 268.[75]

On 26 August 1950, to replenish losses suffered in battle and to build the 7th Cavalry up to its authorized strength, 2nd Battalion-30th Infantry Regiment, from the 3rd Infantry Division, was attached to the 1st Cavalry Division and was redesignated as the 3rd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment.[75] By 5 September, enemy pressure along the sector of the 1st Cavalry Division had increased tremendously.[75] General Gay ordered a general withdrawal of the 1st Cavalry Division in order to shorten lines and occupy better defensive positions. The withdrawal movement began on the right with the 8th Cavalry, then the 7th Cavalry in the Hill 518 area and finally the 5th Cavalry in vicinity of Waegwan. The key to the withdrawal was Hill 464, behind the 2nd Battalion-7th Cavalry, that dominated the Waegwan – Tabu-dong road. The withdrawal was slowed by mud created by heavy rains which fell 5–6 September, hampering the movement of wheeled and tracked vehicles.[75] On 6 September, at 0300 hours, 2-7 Cavalry disengaged from the enemy on Hill 464 and fought its way to the east. The 5th Cavalry, occupying positions on Hill 303, came under heavy fire and was driven from key terrain, however, they were able to recapture the lost ground with the aid of elements of the 70th Tank Battalion attached to the 1st Cavalry Division. During the next few days, the situation was precarious. The North Koreans had gained large footholds east of Naktong and south to within about 8 miles of Taegu in the vicinity of Hills 314 and 570.[75] On 12 September, the 3rd Battalion-7th Cavalry was tasked to retake Hill 314.[75] After a fierce struggle, the hill was taken. The North Korean drive halted on 13 September, seven miles short of Taegu. Their momentum began to slow and plans were laid for an all-out offensive.[75]

The turning point in this bloody battle came on 15 September 1950, when GEN MacArthur unleashed his plan to go around the advancing North Korean Army; Operation Chromite – an amphibious landing at Incheon, far behind the North Korean lines. In spite of the many negative operational reasons given by critics of the plan, the Inchon landing was an immediate success allowing the 1st Cavalry Division to break out of the Pusan Perimeter and start fighting north. Task Force Lynch was formed to execute a rapid breakthrough to link up with the Inchon landing forces; it was composed of the 3rd Battalion-7th Cavalry, B Co 8th Engineer Battalion, C Co and the I&R Platoon of 70th Tank Battalion, 77th Field Artillery Battalion (-), 3rd Platoon Heavy Mortar Company, and a tactical air support liaison team.[75] On 22 September, TF Lynch attacked north, breaking out of the Pusan Perimeter and fighting across 106 miles of enemy territory. On 27 September, north of Osan, at a small bridge, L Co, 3-7 Cavalry, linked up with H Co, 31st Infantry, 7th Infantry Division of the landing force. On 28 September, K Co, 3-7 Cavalry, along with C Co 70th Tank Battalion and with the strong assistance of fighter-bombers, destroyed at least seven of ten North Korean T-34's in the Pyongtaek area, five by air strikes.[75] After linking up with the rest of the 1st Cavalry Division by 4 October, 7th Cavalry continued its advance north, securing Kaesong by the 8th, and crossing the 38th parallel on 9 October 1950. The 7th Cavalry rounded up 2,000 prisoners. In one of the ironic moments of the war, Troopers took into custody a small North Korean cavalry unit and all its horses. The Troopers of the 1st Cavalry crashed into Pyongyang, capturing the capital city of North Korea on 19 October 1950.[2]

In late October 1950, the 7th Cavalry moved north again. The North Korean Army was shattered and the UN Troops were nearing the Chinese border; the war seemed to be all but over. On 25 October, Communist China intervened on behalf of North Korea and began pushing UN Troops back. On 24 November, the 7th Cavalry was involved in a grand UN counterattack, but Chinese attacks shattered the ROK Army II Corps on the 1st Cavalry Division's flank, leaving it exposed. On 26 November, the Chinese penetrated the front companies of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 7th Cavalry and tried to exploit the gap. At 0200 hours they were hit by elements of the 3rd Battalion reinforced by tanks. Red troops were stopped and retreated back into an area previously registered for artillery fire. Enemy losses were high and the shoulder was held. On 29 November, the Chinese attacked the 7th Cavalry again, and the Americans were forced to fall back to Sinchang-ni, North Pyongan Province. At midnight, the Chinese attacked again. They were repulsed, but small infiltration teams managed to attack a Battalion command post before being driven off. At the Battle of Sinchang-ni, 7th Cavalry suffered 39 KIA, 107 WIA, and 11 MIA.[76] Enormous Chinese numbers, the surprise of their attack, and the bitter cold of the North Korean winter forced UN troops to fall back. During the withdrawal, the Greek Army's Sparta Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Georgios Koumanakos was attached to the 7th Cavalry Regiment and became 4th Battalion (GEF)-7th Cavalry on 16 December 1950. The Greeks soon proved themselves to be gallant soldiers in battle.[77] By 28 December 1950, 7th Cavalry Troopers were in defensive positions near Uijeongbu. The year of 1951 would begin as a cold and dark time for the men of the 7th Cavalry. They had been pushed back into South Korea by the Chinese after having seemingly all but defeated North Korean Communist forces, but the fight was not over yet.