Rajput (from Sanskrit raja-putra 'son of a king') is a large multi-component cluster of castes, kin bodies, and local groups, sharing social status and ideology of genealogical descent originating from the Indian subcontinent. The term Rajput covers various patrilineal clans historically associated with warriorhood: several clans claim Rajput status, although not all claims are universally accepted. According to modern scholars, almost all Rajputs clans originated from peasant or pastoral communities.[1][2][3][4][5]

Lineages

Genealogies of the Rajput clans were fabricated by pastoral nomadic tribes when they became sedentary. In a process called Rajputization, after acquiring political power, they employed bards to fabricate these lineages which also disassociated them from their original ancestry of cattle-herding or cattle-rustling communities and acquired the name 'Rajput'.[6][7][8][9][10][5] There are three basic lineages (vanshas or vamshas) among Rajputs. Each of these lineages is divided into several clans (kula) (total of 36 clans).[11] Suryavanshi denotes descent from the solar deity Surya, Chandravanshi (Somavanshi) from the lunar deity Chandra, and Agnivanshi from the fire deity Agni. The Agnivanshi clans include Parmar, Chaulukya (Solanki), Parihar and Chauhan.[12]

Lesser-noted vansh include Udayvanshi, Rajvanshi,[13] and Rishivanshi. The histories of the various vanshs were later recorded in documents known as vamshāavalīis; André Wink counts these among the "status-legitimizing texts".[14]

Beneath the vansh division are smaller and smaller subdivisions: kul, shakh ("branch"), khamp or khanp ("twig"), and nak ("twig tip").[15] Marriages within a kul are generally disallowed (with some flexibility for kul-mates of different gotra lineages). The kul serves as the primary identity for many of the Rajput clans, and each kul is protected by a family goddess, the kuldevi. Lindsey Harlan notes that in some cases, shakhs have become powerful enough to be functionally kuls in their own right.[16]

Suryavanshi (Ikshvaku) lineage of Rajputs

The Suryavanshi lineage (also known as the Raghuvanshies or Solar Dynasty) are clans who claim descent from Surya, the Hindu Sun-god.[17]

Suryavanshi Rajput Clans

Chandravansh lineage of Rajputs

The Chandravanshi lineage (Somavanshi or Lunar Dynasty) claims descent from Chandra, The lineage is further divided into Yaduvansh dynasty descendants of King Yadu and Puruvansh dynasty descendants of King Puru.[17]

Chandravanshi Clans

Yaduvanshi Clans

Agnivanshi lineage of Rajputs

The Agnivanshi lineage claim descent from Agni, the Hindu god of fire.[17]

Agnivanshi Clans

- Parihar

- Parmar (Panwar)

- Chauhan

- Solanki (clan)

Battalion (Regiment) Clans of Rajputs

In medieval Indian history, Rajputs made several regiments, special battalions and mercenaries specially during Rajput Era to fight against foreign invaders which consisted of Rajput soldiers from some or all Rajput clans. Their descendents still use those regiment Rajput surnames [21][22][23]

Regiment Clans

Purbiya (or Purabia) are Rajput led mercenaries and soldiers from the eastern Gangetic Plain – areas corresponding to present-day western Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh.[23][24]

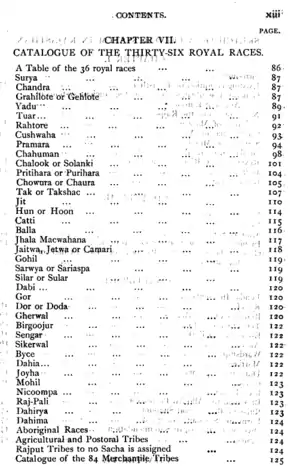

36 royal races

The 36 royal races (Chathis Rajkula) is a listing of Indian social groups purported to be the royal (ruling) clans of several states and Janapads spread over northern Indian subcontinent. Among the historical attempts at creating a comprehensive listing of the 36 are the Kumarapala Prabandha of Acharya Jinamandan Gani of 1435 AD,[25] Prithviraj Raso of uncertain date, and Colonel James Tod, writing in 1829.

Kumarapala Prabandha list

The Kumarpal Prabandha (about the reign of Kumarapala Solanki of Chaulukya dynasty r. 1143-1172 CE) list gives 36 clans. It starts with dynasties mentioned in the classics, Surya and its Ikshvaku sub-branch, Chandra and its Yadu ( Yadava ) branch. It also mentions some of the later famous clans: Parmar, Chauhan, Chaulukya (Solanki), Pratihara Ratt, Chandela and Pala. It also mentions other Deccani dynasties like Shilahara, Chapotkata, Nikumbh etc. Many of the names are less known. Notably, it includes the Mourya. Kumarpal Prabandha was consulted by Tod,[26] he refers to it as Kumarpal Charit.[27]

Tod's list

A listing of the 36 was attempted by Tod in his 1829 work Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan (volume 1). The "races" are further subdivided into 157 branches ( i.e. sakhas), and genealogical, cultural, and geographic information given for each, though some of the sakhas are extinct.[28]

The principal ones like the Ghilote having 24 sub-branches, the Tuar or Tanwar or Toor 17, the Rathor 13, the Parmara 35, the Chamhan or Chauhan 26, the Challook or Solanki 16, and the Pratihara 12. Each sakha has its Gotracharya of genealogical creed describing the characteristics, religious practices, and the locale of the clan.[29]

As early as 1872, Tod's list was criticised in the Calcutta Review:

It seems a pity that Tod's classification of 36 royal races should be accepted as anything but a purely ornamental arrangement, founded as it was on lists differing considerably both in the numbers and names of the tribes included in it...[30]

Tod listed the Jats as one of the 36 royal races. The Persian form of the ancient term Jit is Jatt (जट्ट) with short vowel and double short ‘t’.[31] Tod included "Raj Pali" on the list and described them as Aheer or Ahir.[32][33]

See also

References

- ↑ Eugenia Vanina 2012, p. 140:Regarding the initial stages of this history and the origin of the Rajput feudal elite, modern research shows that its claims to direct blood links with epic heroes and ancient kshatriyas in general has no historic substantiation. No adequate number of the successors of these epically acclaimed warriors could have been available by the period of seventh-eights centuries AD when the first references to the Rajput clans and their chieftains were made. [...] almost all Rajput clans originated from the semi-nomadic pastoralists of the Indian north and north-west.

- ↑ Daniel Gold (1 January 1995). David N. Lorenzen (ed.). Bhakti Religion in North India: Community Identity and Political Action. State University of New York Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-7914-2025-6.

Paid employment in military service as Dirk H. A. Kolff has recently demonstrated, was an important means of livelihood for the peasants of certain areas of late medieval north India... In earlier centuries, says Kolff, "Rajput" was a more ascriptive term, referring to all kinds of Hindus who lived the life of the adventuring warrior, of whom most were of peasant origins.

- ↑ Doris Marion Kling (1993). The Emergence of Jaipur State: Rajput Response to Mughal Rule, 1562–1743. University of Pennsylvania. p. 30.

Rajput: Pastoral, mobile warrior groups who achieved landed status in the medieval period claimed to be Kshatriyas and called themselves Rajputs.

- ↑ André Wink (1991). Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest : 11th-13th Centuries. BRILL. p. 171. ISBN 90-04-10236-1.

...and it is very probable that the other fire-born Rajput clans like the Caulukyas, Paramaras, Cahamanas, as well as the Tomaras and others who in the eighth and ninth centuries were subordinate to the Gurjara-Pratiharas, were of similar pastoral origin, that is, that they originally belonged to the mobile, nomadic groups...

- 1 2 Richard Eaton 2019, p. 87, In Gujarat, as in Rajasthan, genealogy proved essential for making such claims. To this end, local bards composed ballads or chronicles that presented their patrons as idea warriors who protected Brahmins, cows and vassals, as opposed to the livestock herding chieftains that they actually were, or had once been. As people, who created and preserved the genealogies, local bards therefore played critical roles in brokering for their clients socio-cultural transitions to a claimed Rajput status. A similar thing was happening in the Thar desert region, where from the fourteenth century onwards mobile pastoral groups gradually evolved into landed, sedentary and agrarian clans. Once again, it was bards and poets, patronized by little kings, who transformed a clan's ancestors from celebrated cattle-herders or cattle-rustlers to celebrated protectors of cattle-herding communities. The difference was subtle but critical, since such revised narratives retained an echo of a pastoral nomadic past while repositioning a clan's dynastic founder from pastoralist to non-pastoralist. The term 'Rajput', in short, had become a prestigious title available for adoption by upwardly mobile clan in the process of becoming sedentary. By one mechanism or another, a process of 'Rajputization' occurred in new states that emerged from the turmoil following Timur's invasion in 1398, especially in Gujarat, Malwa and Rajasthan.

- ↑ Mayaram, Shail (2010). "The Sudra Right to Rule". In Ishita Banerjee-Dube (ed.). Caste in History. Oxford University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-19-806678-1.

In their recent work on female infanticide, Bhatnagar, Dube and Bube(2005) distinguish between Rajputization and Sanksritization. Using M.N.Srinivas' and Milton Singer's approach to social mobility as idioms they identify Rajputization as one of the most dynamic modes of upward mobility. As an idiom of political power it 'signifies a highly mobile social process of claiming military-political power and the right to cultivate land as well as the right to rule. Rajputization is unparalleled in traditional Indian society for its inventiveness in ideologies of legitimation and self-invention. This was a claim that was used by persons of all castes all over north India ranging from peasants and lower-caste Sudras to warriors and tribal chiefs and even the local raja who had recently converted to Islam.

- ↑ André Wink (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7th-11th Centuries. BRILL. p. 282. ISBN 0-391-04173-8.

In short, a process of development occurred which after several centuries culminated in the formation of new groups with the identity of 'Rajputs'. The predecessors of the Rajputs, from about the eighth century, rose to politico-military prominence as an open status group or estate of largely illiterate warriors who wished to consider themselves as the reincarnates of the ancient Indian Kshatriyas. The claim of Kshatriyas was, of course, historically completely unfounded. The Rajputs as well as other autochthonous Indian gentry groups who claimed Kshatriya status by way of putative Rajput descent, differed widely from the classical varna of Kshatriyas which, as depicted in literature, was made of aristocratic, urbanite and educated clans...

- ↑ Thomas R. Metcalf (1990). Modern India: An Interpretive Anthology. Sterling Publishers. p. 90. ISBN 9788120709003.

Since then every known royal family has come from a non - Kshatriya caste , including the famous Rajput dynasties of medieval India . Panikkar also points out that " the Shudras seem to have produced an unusually large number of royal families even in more recent times"

- ↑ Koyal, Sivaji (1986). "Emergence of Kingship, Rajputization and a New Economic Arrangement in Mundaland". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Indian History Congress. 47, I: 536–542. JSTOR 44141600.

- ↑ Ishita Banerjee-Dube (2010). Caste in History. Oxford University Press. p. xxiii. ISBN 978-0-19-806678-1.

Rajputization discussed processes through which 'equalitarian, primitive, clan based tribal organization' adjusted itself to the centralized hierarchic, territorial oriented political developments in the course of state formation. This led a 'narrow lineage of single families' to disassociate itself from the main body of their tribe and claim Rajput origin. They not only adopted symbols and practices supposedly representative of the true Kshatriya, but also constructed genealogies that linked them to the primordial and legendary solar and lunar dynasties of kings. Further, it was pointed out that the caste of genealogists and mythographers variously known as Carans, Bhats, Vahivanca Barots, etc., prevalent in Gujarat, Rajasthan and other parts of north India actively provided their patron rulers with genealogies that linked local clans of these chiefs with regional clans and with the Kshatriyas of the Puranas and Mahabharata. Once a ruling group succeeded in establishing its claim to Rajput status, there followed a 'secondary Rajputization' when the tribes tried to 're-associate' with their formal tribal chiefs who had also transformed themselves into Hindu rajas and Rajput Kshatriyas.

- ↑ Jai Narayan Asopa (1990). A socio-political and economic study, northern India. Prateeksha Publications. p. 89. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ↑ Maya Unnithan-Kumar (1997). Identity, Gender, and Poverty: New Perspectives on Caste and Tribe in Rajasthan. Berghahn Books. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-57181-918-5. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ Makhan Jha (1 January 1997). Anthropology of Ancient Hindu Kingdoms: A Study in Civilizational Perspective. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-81-7533-034-4. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ André Wink (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7th-11th Centuries. BRILL. pp. 282–. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ Shail Mayaram 2013, p. 269.

- ↑ Lindsey Harlan 1992, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Barbara N. Ramusack (2003). The Indian Princes and their States, The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9781139449083.

- ↑ Valisinha, Devapriya (1948). Buddhist shrines in India.

- ↑ Ansari, Saiyad Hasan (27 September 1986). ""Evolution and Spatial Organization of Clan Settlements: A Case Study of Middle Ganga Valley"".

- ↑ A H Bingley (1986). Hand Book On Rajputs.

- ↑ History of Tomars, Part1 – Tomars of Delhi by Harihar niwas Dwivedi. Gwalior: Vidyamandir publications. 1983.

- ↑ Tarikh-i-Firishta, tr. Briggs, Vol.1. p. 26.

- 1 2 Waltraud Ernst; Biswamoy Pati (18 October 2007). India's Princely States: People, Princes and Colonialism. Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-134-11988-2.

- ↑ M. S. Naravane (1999). The Rajputs of Rajputana: A Glimpse of Medieval Rajasthan. APH Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 978-81-7648-118-2.

- ↑ Jai Narayan Asopa (1990). A socio-political and economic study, northern India. Prateeksha Publications. p. 89. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ↑ Some Medieval Sculptures of North Gujarat, H. A. Majmudar, Gujarat University, 1968, p. 155

- ↑ Jai Narayan Asopa (1990). A socio-political and economic study, northern India. Prateeksha Publications. p. 94. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ↑ Sir Chirravoori Yajneswara Chintamani (1901). Indian social reform: being a collection of essays, addresses, speeches, &c., with an appendix. Thompson. pp. 154–. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ↑ Sir Chirravoori Yajneswara Chintamani, "Indian social reform: being a collection of essays, addresses, speeches", page 155

- ↑ University of Calcutta (1872). Calcutta review. University of Calcutta. pp. 386–. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ↑ Raza, S. Jabir (2004). The Jats of Punjab and Sind: Their settlements and migrations (c. 5th-12th AD). Vol. 1.

- ↑ Tod, James (1832). "Annales and antiquities of Rajasthan, or the central and western Rajpoot states of Indian". Smith Original : Austrian National Library. p. 443. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ Association of Population Geographers of India (1988). "Population Geography: A Journal of the Association of Population Geographers of India, Volume 10, Issues 1-2". The Association Original : the University of California. p. xi. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

Bibliography

- Richard Eaton (2019). India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-196655-7.

- Eugenia Vanina (2012). Medieval Indian Mindscapes: Space, Time, Society, Man. Primus Books. ISBN 978-93-80607-19-1.

- Shail Mayaram (2013). Against History, Against State: Counterperspectives from the Margins. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52951-8.

- Lindsey Harlan (1992). Religion and Rajput Women: The Ethic of Protection in Contemporary Narratives. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07339-5.

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1952), Joseph Campbell (ed.), Philosophies of India, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6

External links

- Rajasthan and the Rajputs

- The Thirty-six Royal Races of Rajput at Kipling.org