| Mauritania–Senegal Border War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

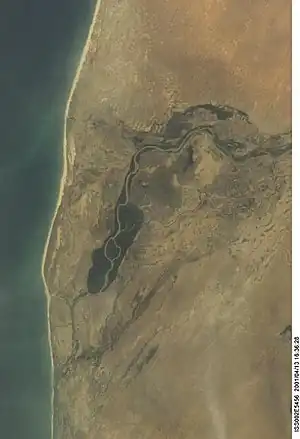

NASA image of the Senegal River valley: Mauritania is located to the north and Senegal is located to south. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000[1] | 14,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Hundreds dead | Hundreds dead | ||||||

| 250,000 displaced | |||||||

The Mauritania–Senegal Border War was a conflict fought between the West African countries of Mauritania and Senegal along their shared border from 1989 to 1991. The conflict began around disputes over the two countries' River Senegal border and grazing rights. The conflict resulted in the rupture of diplomatic relations between the two countries for several years, the creation of thousands of refugees from both sides, as well as having a significant impact on domestic Senegalese politics. Ethnic tension, political/economic crises in Senegal, and competition for natural resources between the two nations were the main underlying causes of this conflict.

Background

Ethnic History of Senegal River Region

The Senegal River basin between Mauritania and Senegal has for centuries been inhabited by both black populations, such as the Fula, Toucouleur, Wolof, Bambara, and Soninké, and by Arabs and Berber peoples (often referred to as 'Moors'). The population of Mauritania at the time of the conflict was, and still generally is, divided into three broad ethno-racial categories: 'Beydan' (meaning 'masters'; Arabic-speaking Moors), 'Haratin' (meaning 'slaves'; black Arabic-speaking Mauritanians), and non-Moorish individuals belonging to the ethnically black populations. Members of the Beydan category stand at the top of Mauritania's social hierarchy. They are of Arab and Berber descent. The Beydan have historically maintained political control of the Mauritanian state. Below the Beydan in the social hierarchy are the Haratin. Members of the Haratin category are ethnically black and are either former slaves themselves or the descendants of slaves, since the official abolition of slavery in Mauritania in 1980. While slavery is officially abolished in Mauritania, the enforcement of abolition is rare, leaving many black Mauritanians still enslaved. Today, Haratin refers to freed slaves, while the term 'Abid' refers to enslaved black Mauritanians. The Haratin and Abid generally speak Arabic and have assimilated into the Arabic culture of the Beydan. At the bottom of Mauritania's social hierarchy are the ethnically black populations who have retained the local and regional languages of their ethnic groups (Fula, Wolof, Bambara, etc.) and have not assimilated into Arabic culture. These groups typically reside in the southern region of Mauritania, along the river basin. Since the mid-1960s, many ethnically black Mauritanians have fought against what they call the "Arabization" of Mauritania. The ethnic tension between these three groups was a major contributor to the violence beginning in 1989.[2][3][4][5]

Political and Economic Factors

In the years leading up to the war, Senegal experienced serious economic instability and political unrest. Economic repercussions of recent drought in the region, along with the implementation of structural adjustment agreements with the International Monetary Fund, caused the weakening of Senegal's already fragile economy during the 1980s. The unemployment rate in Senegal also rose throughout the decade as a result of stagnated economic production. Following the 1988 parliamentary elections in Senegal, members of the Parti Democratique Senegalese (PDS), the main opposition to the majority Parti Socialiste (PS), contested the election results and were subsequently imprisoned by the administration of Senegalese president, Abdou Diouf. This political unrest and economic instability caused increasing frustration for the people of Senegal.[3]

Mauritania's attempts at land reform in 1983 strengthened the role of the state while undermining traditional agriculture, worsening the problems of many farmers on both sides of the border. These ordinances passed in Mauritania authorized the central government to expropriate land in the southern region of the country, which was mainly occupied by ethnically black Mauritanians, and allot the land to Beydan Mauritanians in the north.[3] Disputes over which country controlled the land on either side of the Senegal River, as well as which ethnic groups held grazing rights for the land, persisted throughout the decade.

Mauritania and Senegal shared strong economic ties, both formal and informal, prior to the conflict. At the time, both countries were members of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Citizens of the two countries also engaged in informal, cross-border trade of crops, livestock, and various consumer goods, which was essential to the economies of both countries. Once the conflict began, the informal trade economy fell apart.[3]

Natural Resources

Desertification caused by periods of drought throughout the 1980s increased tensions over available arable land. This proved to be a significant issue because the majority of agriculture in the region had been rainfed, with only few areas being irrigated by the river. The creation of the Organisation pour la mise en valeur du fleuve Sénégal (OMVS; in English, Senegal River Basin Development Authority) in 1972, which constructed dams and other irrigation projects, such as the Diama Dam, was intended to preserve the land of the Senegal River Basin through joint cooperation. The project, however, disrupted the balance between herders and farmers by opening new parts of the valley to irrigation, ultimately leading to greater tension between the two countries. Maaouya Ould Sid'Ahmed Taya, president of Mauritania at the time, and Abdou Diouf, president of Senegal at the time, also engaged in a dispute after the completion of the dams. President Ould Taya argued that Senegalese representatives in OMVS refused to create river harbors during the construction, which blocked Mauritania's ability to exploit phosphate deposits.[2][3][6] Throughout history, inhabitants of the land north and south of the Senegal River relied on farming, pastoralism, and fishing as a main source of income and sustenance. The development of the gum trade and urbanization in the Senegal River region led to the development of new communities on either side of the river. Increased access to water allowed previously nomadic groups to settle throughout the region.[6]

Deterioration of Relations

Both Mauritania and Senegal are former French colonies; however, since Mauritania's independence, many members of the Mauritanian government have sought to reinforce the Arab identity of the state, including the strengthening of ties with the Arab world. At the time of the conflict, the Mauritanian government was divided into two political factions: the "Baathists", backed by Iraq, and the "Naseerites", who politically supported Libya. Senegal, in comparison, remained attached to the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, resulting in increasingly divergent foreign policies in the two countries.[3]

All of these factors led to a deterioration in relations between Mauritania and Senegal, with both countries hardening their stances against each other with each further incident. This created an explosive situation that was stirred up by both countries' domestic news media, which focused heavily on the ethnic dimensions to the conflict.[7]

Conflict

Border Violence and Ethnic Clashes

On 8 April 1989, there was a clash between Senegalese Soninke farmers and Mauritanian Fulani herdsmen in Mauritania over grazing rights in Diawara, a town in the Bakel Department of eastern Senegal. This event marked the beginning of the conflict. The clash took place because the Senegalese herdsmen confiscated a herd of cattle belonging to the Mauritanian farmers after the cattle migrated into Senegalese territory. The confiscation of the cattle was in accordance with an earlier agreement made between Senegal and Mauritania over grazing rights and territorial control. Despite this, Mauritanian border guards intervened after spotting a group of Senegalese farmers who had crossed into Mauritanian controlled territory. The border guards fired at the group, killing at least two Senegalese peasants, as well as seriously injuring several more, and taking between 12 and 15 Senegalese farmers hostage. Official reports of the incident from Senegal and Mauritania provide conflicting details, as the Senegalese government claims the attackers were border guards, and the Mauritanian government claims the attackers were Mauritanian farmers.[3][8]

The Mauritanian Interior Minister, Djibril Ould Abdoullahi, traveled to Dakar, Senegal a few days after the attack to speak on Senegalese television. Abdoullahi made comments about the importance of the event, which many Senegalese citizens interpreted as discounting the severity of the event and making light of those who died.[9]

As a result of the 8 April attack and the subsequent comments by Abdoullahi, Senegalese citizens on the southern bank rioted, escalating the conflict. Between April 21–24, 1989, Senegalese mobs looted and burned shops owned by Mauritanian traders in Dakar, killing 61 Mauritanians. On 25 April, Mauritanian soldiers and border guards in Southern Mauritania retaliated by beating to death at least 200 Senegalese citizens in an event now referred to as 'Black Tuesday'. The violence between April 21–25, led to a mass exodus of refugees from both sides.[9]

Between April 27–29, Senegalese citizens orchestrated attacks against individual Mauritanians living in Dakar, leading to the deaths of at least 50 Mauritanians. Simultaneously in Mauritania, Arab Moors attacked and killed individual Senegalese nationals and even some black Mauritanians. Both countries deployed their armies internally to control the violence and both governments implemented curfews.[3][9]

On 21 August 1989, the border was closed, and diplomatic relations between Mauritania and Senegal came to an end.[10]

Repatriation and Expulsion

In late April, both governments began the process of repatriating foreign nationals from each country. With assistance from the governments of France, Spain, Algeria, and Morocco, Mauritania and Senegal returned approximately 250,000 refugees to their country of origin.[3][8] Approximately 75,000 Senegalese nationals returned to Senegal and 170,000 Mauritanian nationals returned to Mauritania.[9] In some cases, individuals who were repatriated had no links to the country to which they were repatriated, as they had lived outside of their home country for so long. During this process, the Mauritanian government also expelled many black Mauritanian citizens under the guise of refugee repatriation. These Mauritanian citizens were sent to Senegal without any way of returning to Mauritania.[6]

Mediation Efforts

Following the mass-repatriation and expulsion, the situation seemed temporarily under control. Violence decreased, but the tensions between the two countries remained. Mediation efforts by the Maghreb Union, Organisation of African Unity (OAU), Mali, Nigeria, Togo, Guinea, Gambia, the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (now the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation), Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, France, Egypt, Morocco, and the United Nations all failed to help both sides reach an agreement.[3][11]

In September 1989, Egyptian president and newly elected chairman of the OAU, Hosni Mubarak, held a mediatory meeting between representatives from Senegal and Mauritania. The Mauritanian officials argued that hundreds of thousands of Mauritanians were being held hostage in Senegal and that Mauritanians were owed compensation for the massive amounts of goods they owned that were looted and destroyed by the Senegalese. The Senegalese representatives argued that the Mauritanian government had expelled a large number of black Mauritanian nationals to Senegal during the repatriation process. They also argued that the true border between the countries lay north of the river, according to a 1933 French colonial decree, and that Senegalese citizens were owed compensation for their goods destroyed by Mauritanians. The issues of compensation and the location of the border were the most important to each side and were also the most inflexible of all the issues. The two sides failed to reach a compromise.[3]

Military Engagement

On October 24, 1989, there was a direct military engagement between the official militaries of Mauritania and Senegal, the first since the beginning of the conflict in April. In November 1989, the government of Iraq supplied Mauritania with a large quantity of weapons and over 30 military advisors. The government of Syria supplied Mauritania with a radar system. These additions allowed Mauritania to significantly increase its military operations. On January 6, 1990, both armies engaged in a heavy artillery battle near the village of Doundou, Senegal.[9][11] Fighting continued in short bursts until the summer of 1991.[3]

Senegalese military forces fought alongside the African Liberation Forces of Mauritania (FLAM), a militant organization of exiled black Mauritanians based in Senegal. FLAM heavily recruited black Mauritanians who had been exiled by Mauritania during the refugee repatriation process.[3]

Aftermath

In July 1991, presidents Abdou Diouf and Maaouya Ould Sid'Ahmed Taya reached an agreement to end hostilities. On 18 July, Senegal and Mauritania signed a peace treaty, ending the Mauritania–Senegal Border War. On May 2, 1992, the border reopened to civilians.[10]

In terms of domestic politics in Senegal, the conflict may have contributed to the rise of the PDS and Abdoulaye Wade due to the then governments inability to deal with the social crisis caused by the influx of vast numbers of refugees. Senegal was further undermined by its neighbors following the war, with problems arising over the demarcation of the border with Guinea-Bissau in the wake of the conflict, and difficulties with the Gambia leading to the dissolution of the Senegambia Confederation in 1989. The period of conflict has also had a lasting impact on relations between Mauritania and Senegal as well as domestic perceptions of each other.

As of May 2014, approximately 16,000 black Mauritanian refugees still live in Senegal, despite the United Nations officially closing Mauritanian refugee camps in Senegal. The majority of these 16,000 refugees have chosen to stay in Senegal following a recent United Nations led voluntary repatriation of approximately 25,000 Mauritanians. The refugees remaining in Senegal have cited their access to healthcare and education, as well as fear of ethnic persecution in Mauritania, as the reasons for staying. The government of Mauritania has since recognized the Mauritanian citizenship of all Mauritanian refugees in Senegal and has agreed to their repatriation on a case-by-case basis, but the remaining refugees choose not to return. In May 2014, thousands of these remaining Mauritanian refugees marched approximately 300 km (186 mi) to Nouakchott, Mauritania and demanded the return of, or compensation for, property seized by the Mauritanian government after the initial refugee repatriation in 1989. The refugees and their demands were not welcomed by the Mauritanian government. The refugees returned to Senegal without compensation.[12]

Serious ethnic divides in Mauritania still persist today. There are currently an estimated 90,000 individuals still living in chattel slavery in Mauritania and an additional estimated 500,000 individuals living in "slave-like conditions".[4]

References

- 1 2 Rone Tempest (3 June 1989). "In Senegal and Mauritania, Ethnic Conflict Rages Amid Talk of War". LA Times. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- 1 2 Kipping, Martin (2009), Water Security in the Senegal River Basin: Water Cooperation and Water Conflicts, Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace, vol. 4, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 675–684, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-68488-6_51, ISBN 978-3-540-68487-9, retrieved 2023-04-30

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Africa – Rivista Trimestriale di Studi e Documentazione dell'Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente". African Studies Companion Online. doi:10.1163/_afco_asc_711. Retrieved 2023-04-10.

- 1 2 King, Stephen J. (26 August 2021). "Ending Hereditary Slavery in Mauritania: Bidan (Whites) and Black "Slaves" in 2021". Arab Reform Initiative.

- ↑ "Central Intelligence Agency, Memorandum, The Will and Ability of Certain Countries to Support and Develop Their Armed Forces, from Their Own Resources and with US Aid, April 19, 1949, Top Secret, CREST". U.S. Intelligence on the Middle East, 1945-2009. doi:10.1163/9789004249028.b01257. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- 1 2 3 Fall, Aziz Salmone (March 26, 2010). "Conflict in the Senegal River Valley". Cultural Survival.

- ↑ Ahmedou, Hamdi (2018), "Rapatriés et conflits fonciers dans la vallée du fleuve Sénégal", Foncier, droit et propriété en Mauritanie, Centre Jacques-Berque, pp. 151–172, doi:10.4000/books.cjb.1306, ISBN 979-10-92046-36-6, retrieved 2023-04-23

- 1 2 Hall, Michael R. (2011). Mauritania-Senegal Border War (1989-1991). In A. Mikaberidze (Ed.), Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia (pp. 565-566). ABC-CLIO.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Parker, Ron (March 1991). "The Senegal–Mauritania Conflict of 1989: a Fragile Equilibrium". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 29 (1): 155–171. doi:10.1017/s0022278x00020784. ISSN 0022-278X. S2CID 154799500.

- 1 2 "Communal Violence in Mauritania and Senegal 1989-1992". Climate Diplomacy. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- 1 2 Bercovitch, Jacob; Fretter, Judith (2004). Regional Guide to International Conflict and Management from 1945 to 2003. 2300 N Street, NW, Suite 800, Washington DC 20037 United States: CQ Press. doi:10.4135/9781452240169. ISBN 978-1-56802-825-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Mauritanian refugees refuse to leave Senegal, retrieved 2023-04-30