Title page of 1st edition | |

| Author | Daniel Hudson Burnham Edward H Bennett |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Jules Guérin |

| Subject | Urban planning |

| Published | 1909 (Commercial Club of Chicago) |

| Pages | 164 |

| OCLC | 2630602 |

| Limited edition of 1650 copies | |

The Burnham Plan is a popular name for the 1909 Plan of Chicago, co-authored by Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett and published in 1909. It recommended an integrated series of projects including new and widened streets, parks, new railroad and harbor facilities, and civic buildings. Though only portions of the plan were realized, the document reshaped Chicago's central area and was an important influence on the new field of city planning.

The project was begun in 1906 by the Merchants Club, which merged with the Commercial Club of Chicago, a group of prominent businessmen who recognized the necessity of improvements to the fast-growing city. They retained Daniel H. Burnham, an architect who had managed the construction of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. After the fair, he had presented ideas for improving Chicago's lakefront, and had worked on city plans for Washington, D.C., Cleveland, and San Francisco, and Manila and Baguio in the Philippines. Burnham retained Edward Bennett as co-author, and a small staff to help prepare the plan. Charles Moore edited the finished manuscript, and renderer Jules Guérin created several bird's-eye views for the full-color document, which was printed in lavish book form and presented to the city in July 1909.

Aspects of the plan

The Burnham Plan focused on six major elements:

Improvement of the lakefront

Foremost among the plan's goals was reclaiming the lakefront for the public. "The Lakefront by right belongs to the people," wrote Burnham. "Not a foot of its shores should be appropriated to the exclusion of the people." The plan recommended expanding the parks along the Lake Michigan shoreline with landfill, which was done in the early 20th century. Of the city's 29 miles (47 km) of lakefront, all but four miles (six kilometers) are today public parkland. The plan also provided for extensive lakefront harbor facilities, which became unnecessary with the city's development of facilities in the Lake Calumet regions.

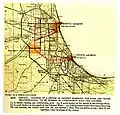

A regional highway system

The plan considered Chicago as the center of a region extending 75 miles (120 km) from the city centre. At the dawn of the automobile age, the plan diagramed both radial and circumferential highways for the region. However, the agencies who built and improved highways in the 1910s and 1920s do not appear to have been guided to build along the specific routes recommended in the plan.

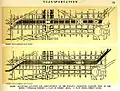

Improvement of railway terminals

The plan drew on technical studies previously done by others, including a plan for competing railroads to pool usage of tracks for greater efficiency in freight handling. In addition, the plan detailed the consolidation of Chicago's six intercity railroad passenger terminals into new complexes west of the Loop and south of Roosevelt Road. This, in turn, would allow the expansion of the business district southward. A new Chicago Union Station was finished in 1925, but no other stations were consolidated or relocated. In 1929, the South Branch of the Chicago River was rechanneled, between Polk and 18th Streets, to untangle railroad approaches as recommended by the plan.

New outer parks

The movement to purchase and preserve the natural areas that became the Cook County Forest Preserves was well under way as the plan was being written. The plan includes those proposals and also calls for the expansion of the city's park and boulevard system, which had been first established in the 1870s.

Systematic arrangement of streets

New wider arterials were prescribed to relieve traffic congestion and beautify the fast growing city, including a network of new diagonal streets. One of these diagonals was constructed: the extension of Ogden Avenue and there are several other diagonal streets throughout the city. Many of the plan's street recommendations were followed. The city renovated, widened, and extended Michigan Avenue, widened Roosevelt Road, and created Wacker Drive and Ida B. Wells Drive (formerly Congress Parkway). With the growth in automobile usage after World War I, Chicago planners began to drastically alter or step away from Burnham's proposals for the street system.[1] Some 108 miles (174 km) of arterial streets were widened between 1915 and 1931, spurred by the tremendous growth in automobile usage. Writing in 1908, Burnham saw the automobile as a recreational vehicle that would allow city dwellers to visit the countryside; he did not foresee how it would overwhelm and transform the city itself.

Civic and cultural centers

The most iconic image of the plan was the new civic center proposed for the area around Congress and Halsted Streets. However, city officials who preferred the convenience of a Loop location never seriously pursued the proposal. At the east end of Congress Street, which would become the central axis of the reshaped city, Burnham proposed a cultural center in Grant Park consisting of the new Field Museum of Natural History and new homes for the Art Institute of Chicago and the Crerar Library. This proposal, however, placed Burnham and other civic leaders in conflict with a state supreme court decision forbidding any new buildings in Grant Park.

Implementation

Although Burnham died in 1912, the Plan of Chicago was promoted by Commercial Club members and the Chicago Plan Commission. They persuaded the mayor of Chicago to appoint co-author Edward H. Bennett, a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts, and he advised various public agencies as they constructed the projects recommended by the plan, using a design vocabulary reminiscent of 19th century Paris. Mayor William Hale Thompson, elected in 1915, used Plan of Chicago projects to promote his image as a Chicago booster, and as a rich source of public contracts.

The plan has been criticized for its focus on physical improvements, an attempt to create "Paris on the Prairie". Burnham's handwritten draft of the plan contained extensive discussion of social needs, but the final publication does not.[2] The plan's list of big infrastructure improvements were badly needed by a rapidly growing city, at a time when an expanding tax base made it possible to undertake large projects.

Enthusiasm for the Burnham Plan's specific proposals faded with the onset of the Great Depression, but aspects of the plan continued to guide planners as they expanded parks, built new bridges, and laid out the city's superhighway network. Civic leaders still make frequent reference to Burnham's vision for the city, and to an aphorism posthumously attributed to him, the oft-quoted exhortation to "make no little plans."

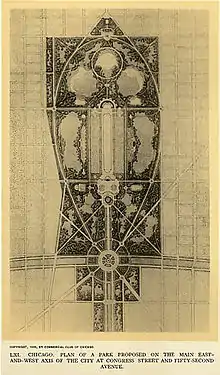

Plan of a park

Plan of a park Diagram of a system of freight handling

Diagram of a system of freight handling Suggested docks at the mouth of the Chicago River

Suggested docks at the mouth of the Chicago River Suggested location and arrangement of railway passenger stations

Suggested location and arrangement of railway passenger stations Theoretical diagram of street circulation

Theoretical diagram of street circulation Intersection of the three branches of the Chicago River

Intersection of the three branches of the Chicago River

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kling, Samuel (2013). "Wide Boulevards, Narrow Visions". Journal of Planning History. 12 (3): 245–268. doi:10.1177/1538513213476709. S2CID 108949272.

- ↑ Schaffer, Kristin. Introduction to Plan of Chicago (reprint), Princeton Architectural Press, 1993.

Further reading

- James R. Grossman, Ann Durkin Keating, Janice L. Reiff. The Encyclopedia of Chicago (University of Chicago Press 2005) ISBN 0-226-31015-9; The Encyclopedia of Chicago (online version)

- The Plan of Chicago (reprint ed.). Princeton Architectural Press. 1993. ISBN 978-1-878271-41-9.

- Smith, Carl (2006). The Plan of Chicago: Daniel Burnham and the Remaking of the American City. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-76471-0.

- The Plan of Chicago: A Regional Legacy

External links

- Burnham Plan of Chicago at the Internet Archive

- Burnham Plan of Chicago in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Educational website created for the centenary of the Plan

- Encyclopedia of Chicago entries 1 2 3

- Photographs held by Lake Forest College Library showing Burnham, Bennett, committee members, and staff at work.

- Online copy