| Z | |

|---|---|

| Z z | |

| |

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Latin script |

| Type | Alphabetic and logographic |

| Language of origin | Latin language |

| Phonetic usage | |

| Unicode codepoint | U+005A, U+007A |

| Alphabetical position | 26 |

| History | |

| Development | |

| Time period | ~700 BC to present |

| Descendants | |

| Sisters | Disputed: ㄷ |

| Other | |

| Other letters commonly used with | z(x), cz, dž, dz, sz, dzs, tzsch |

| Writing direction | Left-to-Right |

| ISO basic Latin alphabet |

|---|

| AaBbCcDdEeFfGgHhIiJjKkLlMmNnOoPpQqRrSsTtUuVvWwXxYyZz |

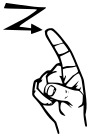

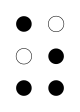

Z, or z, is the 26th and last letter of the Latin alphabet, as used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its usual names in English are zed (/ˈzɛd/) and zee (/ˈziː/), with an occasional archaic variant izzard (/ˈɪzərd/).[1]

Name and pronunciation

In most English-speaking countries, including Australia, Canada, India, Ireland, New Zealand, South Africa and the United Kingdom, the letter's name is zed /zɛd/, reflecting its derivation from the Greek letter zeta (this dates to Latin, which borrowed Y and Z from Greek), but in American English its name is zee /ziː/, analogous to the names for B, C, D, etc., and deriving from a late 17th-century English dialectal form.[2]

Another English dialectal form is izzard /ˈɪzərd/. This dates from the mid-18th century and probably derives from Occitan izèda or the French ézed, whose reconstructed Latin form would be *idzēta,[1] perhaps a Vulgar Latin form with a prosthetic vowel. Outside of the anglosphere, its variants are still used in Hong Kong English and Cantonese.[3]

Other languages spell the letter's name in a similar way: zeta in Italian, Basque, and Spanish, seta in Icelandic (no longer part of its alphabet but found in personal names), zê in Portuguese, zäta in Swedish, zæt in Danish, zet in Dutch, Indonesian, Polish, Romanian, and Czech, Zett in German (capitalised as a noun), zett in Norwegian, zède in French, zetto (ゼット) in Japanese, and zét in Vietnamese. Several languages render it as /ts/ or /dz/, e.g. tseta /tseta/ or more rarely tset /tset/ in Finnish (sometimes dropping the first t altogether; /seta/, or /set/ the latter of which is not very commonplace). In Standard Chinese pinyin, the name of the letter Z is pronounced [tsɨ], as in "zi", although the English zed and zee have become very common. In Esperanto the name of the letter Z is pronounced /zo/.

Under the NATO spelling alphabet, the letter is signified with ZULU, like the Zulu people.

History

| Phoenician Zayin |

Etruscan Z |

Greek Zeta |

|---|---|---|

Semitic

The Semitic symbol was the seventh letter, named zayin, which meant "weapon" or "sword". It represented either the sound /z/ as in English and French, or possibly more like /dz/ (as in Italian zeta, zero).

Greek

The Greek form of Z was a close copy of the Phoenician Zayin (![]() ), and the Greek inscriptional form remained in this shape throughout ancient times. The Greeks called it zeta, a new name made in imitation of eta (η) and theta (θ).

), and the Greek inscriptional form remained in this shape throughout ancient times. The Greeks called it zeta, a new name made in imitation of eta (η) and theta (θ).

In earlier Greek of Athens and Northwest Greece, the letter seems to have represented /dz/; in Attic, from the 4th century BC onwards, it seems to have stood for /zd/ and /dz/ – there is no consensus concerning this issue.[4] In other dialects, such as Elean and Cretan, the symbol seems to have been used for sounds resembling the English voiced and voiceless th (IPA /ð/ and /θ/, respectively). In the common dialect (koine) that succeeded the older dialects, ζ became /z/, as it remains in modern Greek.

Etruscan

The Etruscan letter Z was derived from the Phoenician alphabet, most probably through the Greek alphabet used on the island of Ischia. In Etruscan, this letter may have represented /ts/.

Latin

The letter Z was borrowed from the Greek Zeta, most likely to represent the sound /t͡s/. At c. 300 BC, Appius Claudius Caecus, the Roman censor, removed the letter Z from the alphabet , allegedly due to his distaste for the letter, in that it "looked like the tongue of a corpse". A more likely explanation is the sound had disappeared from Latin, making the letter useless for spelling Latin words. It is also thought due to rhotacism, Z became a trilled R sound, /r/. Whatever the case may be, Appius Claudius' distaste for the letter Z is today credited as the reason for its removal. A few centuries later, after the Roman Conquest of Greece, Z was again borrowed to spell words from the prestigious Attic dialect of Greek.

Before the reintroduction of z, the sound of zeta was written s at the beginning of words and ss in the middle of words, as in sōna for ζώνη "belt" and trapessita for τραπεζίτης "banker".

In some inscriptions, z represented a Vulgar Latin sound, likely an affricate, formed by the merging of the reflexes of Classical Latin /j/, /dj/ and /gj/: for example, zanuariu for ianuariu "January", ziaconus for diaconus "deacon", and oze for hodie "today".[5] Likewise, /di/ sometimes replaced /z/ in words like baptidiare for baptizare "to baptize". In modern Italian, z represents /ts/ or /dz/, whereas the reflexes of ianuarius and hodie are written with the letter g (representing /dʒ/ when before i and e): gennaio, oggi. In other languages, such as Spanish, further evolution of the sound occurred.

Old English

Old English used S alone for both the unvoiced and the voiced sibilant. The Latin sound imported through French was new and was not written with Z but with G or I. The successive changes can be seen in the doublet forms jealous and zealous. Both of these come from a late Latin zelosus, derived from the imported Greek ζῆλος zêlos. The earlier form is jealous; its initial sound is the [dʒ], which developed to Modern French [ʒ]. John Wycliffe wrote the word as gelows or ielous.

Z at the end of a word was pronounced ts, as in English assets, from Old French asez "enough" (Modern French assez), from Vulgar Latin ad satis ("to sufficiency").[6]

Last letter of the alphabet

In earlier times, the English alphabets used by children terminated not with Z but with & or related typographic symbols.[7] In her 1859 novel Adam Bede, George Eliot refers to Z being followed by & when her character Jacob Storey says, "He thought it [Z] had only been put to finish off th' alphabet like; though ampusand would ha' done as well, for what he could see."[8]

Some Latin based alphabets have extra letters on the end of the alphabet. The last letter for the Icelandic, Finnish and Swedish alphabets is Ö, while it is Å for Danish and Norwegian. In the German alphabet, the umlauts (Ä/ä, Ö/ö, and Ü/ü) and the letter ß (Eszett or scharfes S) are regarded respectively as modifications of the vowels a/o/u and as a (standardized) variant spelling of ss, not as independent letters, so they come after the unmodified letters in the alphabetical order. The German alphabet ends with z.

Variant and derived forms

A glyph variant of Z originating in the medieval Gothic minuscules and the Early Modern Blackletter typefaces is the "tailed z" (German geschwänztes Z, also Z mit Unterschlinge). In some Antiqua typefaces, this letter is present as a standalone letter or in ligatures. Ligated with long s (ſ), it is part of the origin of the Eszett (ß) in the German alphabet. The character ezh (Ʒ) resembles a tailed z, which came to be indistinguishable from the yogh (ȝ) in Middle English writing.

Unicode assigns codepoints U+2128 ℨ BLACK-LETTER CAPITAL Z (ℨ, ℨ) and U+1D537 𝔷 MATHEMATICAL FRAKTUR SMALL Z (𝔷) in the Letterlike Symbols and Mathematical alphanumeric symbols ranges respectively.

lowercase cursive z

lowercase cursive z z in a sans serif typeface

z in a sans serif typeface

There is also a variant with a stroke.

Pronunciation and use

| Language | Dialect(s) | Pronunciation (IPA) | Environment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basque | /s̻/ | |||

| Cantonese | Guangzhou and Hong Kong | /ts/ | Exclusive to Jyutping. Other romanizations use either "J", "Ch" or "Ts". | |

| Catalan | Standard | /z/ | ||

| Some Valencian dialects | /s/ | |||

| Czech | /z/ | |||

| Finnish | /ts/ | Only used in loanwords | ||

| French | /z̪/ | Dentalized | ||

| German | Standard | /ts/ | ||

| Galician | Standard | /θ/ | Always | See Galician Phonology |

| Central dialects | /s/ | Coda position | ||

| /θ/ | Elsewhere | |||

| Western dialects | /s/ | Always | ||

| Hungarian | /z/ | |||

| Inari Sami | /dz/ | |||

| Indonesian | /z/ | |||

| Italian | Standard | /dz/ | ||

| /ts/ | ||||

| Japanese | Standard | /dz/ | Before /ɯ/ | Latinization; see Yotsugana |

| /z/ | Elsewhere | |||

| Mandarin | Standard | /ts/ | Pinyin latinization | |

| Northern Sami | /dz/ | |||

| Modern Scots | /g/ | Some words and names | ||

| /j/ | Some words and names | |||

| /z/ | Usually | |||

| Polish | /z/ | |||

| Spanish | Most of European | /θ/ | ||

| American, Andalusian, Canarian | /s/ | |||

| Turkmen | /ð/ | |||

| Venetian | /d/ | Dialectal, archaic | ||

| /dz/ | ||||

| /ð/ | Dialectal, archaic | |||

English

In modern English orthography, the letter ⟨z⟩ usually represents the sound /z/.

It represents /ʒ/ in words like seizure. More often, this sound appears as ⟨su⟩ or ⟨si⟩ in words such as measure, decision, etc. In all these words, /ʒ/ developed from earlier /zj/ by yod-coalescence.

Few words in the Basic English vocabulary begin or end with ⟨z⟩, though it occurs within other words. It is the least frequently used letter in written English,[9] with a frequency of about 0.08% in words. ⟨z⟩ is more common in the Oxford spelling of British English than in standard British English, as this variant prefers the more etymologically 'correct' -ize endings, which are closer to Greek, to -ise endings, which are closer to French; however, -yse is preferred over -yze in Oxford spelling, as it is closer to the original Greek roots of words like analyse. The most common variety of English it is used in is American English, which prefers both the -ize and -yze endings. One native Germanic English word that contains 'z', freeze (past froze, participle frozen) came to be spelled that way by convention, even though it could have been spelled with 's' (as with choose, chose and chosen).

⟨z⟩ is used in writing to represent the act of sleeping (often using multiple z's, like zzzz), as an onomatopoeia for the sound of closed-mouth human snoring.[10]

Other languages

⟨z⟩ stands for a voiced alveolar or voiced dental sibilant /z/, in Albanian, Breton, Czech, Dutch, French, Hungarian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Romanian, Serbo-Croatian, Slovak, and the International Phonetic Alphabet. It stands for /t͡s/ in Chinese pinyin and Jyutping, Finnish (occurs in loanwords only), and German, and is likewise expressed /ts/ in Old Norse. In Italian, it represents two phonemes, /t͡s/ and /d͡z/. In Portuguese, it stands for /z/ in most cases, but also for /s/ or /ʃ/ (depending on the regional variant) at the end of syllables. In Basque, it represents the sound /s/.

Castilian Spanish uses the letter to represent /θ/ (as English ⟨th⟩ in thing), though in other dialects (Latin American, Andalusian) this sound has merged with /s/. Before voiced consonants, the sound is voiced to [ð] or [z], sometimes debbucalized to [ɦ] (as in the surname Guzmán [ɡuðˈman], [ɡuzˈman] or [ɡuɦˈman]). This is the only context in which ⟨z⟩ can represent a voiced sibilant [z] in Spanish, though ⟨s⟩ also represents [z] (or [ɦ], depending on the dialect) in this environment.

In Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish, ⟨z⟩ usually stands for the sound /s/ and thus shares the value of ⟨s⟩; it normally occurs only in loanwords that are spelt with ⟨z⟩ in the source languages.

The letter ⟨z⟩ on its own represents /z/ in Polish. It is also used in four of the seven officially recognized digraphs: ⟨cz⟩ (/t͡ʂ/), ⟨dz⟩ (/d͡z/ or /t͡s/), ⟨rz⟩ (/ʐ/ or /ʂ/, sometimes it represents a sequence /rz/) and ⟨sz⟩ (/ʂ/), and is the most frequently used of the consonants in that language. (Other Slavic languages avoid digraphs and mark the corresponding phonemes with the háček (caron) diacritic: ⟨č⟩, ⟨ď⟩, ⟨ř⟩, ⟨š⟩; this system has its origin in Czech orthography of the Hussite period.) ⟨z⟩ can also appear with diacritical marks, namely ⟨ź⟩ and ⟨ż⟩, which are used to represent the sounds /ʑ/ and /ʐ/. They also appear in the digraphs ⟨dź⟩ (/d͡ʑ/ or /t͡ɕ/) and ⟨dż⟩ (/d͡ʐ/ or /t͡ʂ/).

Hungarian uses ⟨z⟩ in the digraphs ⟨sz⟩ (expressing /s/, as opposed to the value of ⟨s⟩, which is ʃ), and ⟨zs⟩ (expressing ʒ). The letter ⟨z⟩ on its own represents /z/.

In Modern Scots ⟨z⟩ is used in place of the obsolete letter ⟨ȝ⟩ (yogh) and should be pronounced as a hard 'g'. Whilst there are a few common nouns which use ⟨z⟩ in this manner, such as brulzie (pronounced 'brulgey' meaning broil), z as a yogh substitute is more common in people's names and place-names. Often the names are mispronounced to follow the apparent English spelling so Mackenzie is commonly pronounced with a 'z' sound. Menzies, however, still retains the correct pronunciation of 'Mingus'.

Among non-European languages that have adopted the Latin alphabet, ⟨z⟩ usually stands for [z], such as in Azerbaijani, Igbo, Indonesian, Shona, Swahili, Tatar, Turkish, and Zulu. ⟨z⟩ represents [d͡z] in Northern Sami and Inari Sami. In Turkmen, ⟨z⟩ represents [ð].

In the Nihon-shiki, Kunrei-shiki, and Hepburn romanisations of Japanese, ⟨z⟩ stands for a phoneme whose allophones include [z] and [dz]. Additionally, in the Nihon-shiki and Kunrei-shiki systems, ⟨z⟩ is used to represent that same phoneme before /i/, where it's pronounced [d͡ʑ ~ ʑ].

Other systems

A graphical variant of ⟨z⟩ is ⟨ʒ⟩, which has been adopted into the International Phonetic Alphabet as the sign for the voiced postalveolar fricative.

Uses of Z as a symbol

- In mathematics, U+2124 ℤ (DOUBLE-STRUCK CAPITAL Z) is used to denote the set of integers. Originally, was just a handwritten version of the bold capital Z used in printing but, over time, it has come to be used more frequently in printed works too. The variable z is also commonly used to represent a complex number.

- In geometry, z is used to denote the third axis in Cartesian coordinates when representing 3-dimensional space.

- In chemistry, the letter Z is used to denote the Atomic number of an element (number of protons), such as Z=3 for Lithium.

- In electrical engineering, Z is used to denote electrical impedance.

- In astronomy, z is a dimensionless quantity representing redshift.

- In nuclear physics, Z denotes the atomic number and

Z0

denotes a Z boson. - Z has been used by the Russian Armed Forces as an identifying symbol on its military vehicles, during Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Russian civilians have used the symbol to express support for the invasion.[11][12]

Related characters

Descendants and related characters in the Latin alphabet

- Z with diacritics: Ź ź Ẑ ẑ Ž ž Ż ż Ẓ ẓ Ẕ ẕ Ƶ ƶ ᵶ[13] Ᶎ[14] ᶎ[15] Ⱬ ⱬ

- ß : German letter regarded as a ligature of long s (ſ) and short s, called scharfes S or Eszett. (In some typefaces and handwriting styles it is rather a ligature of long s and tailed z (ſʒ).)

- Ȥ ȥ: Latin letter z with a hook, intended for the transcription of Middle High German, for instances of the letter z with a sound value of /s/.

- Ɀ ɀ : Latin letter Z with swash tail

- Ʒ ʒ : Latin letter ezh

- Ꝣ ꝣ : Visigothic Z

- Ᶎ ᶎ : Z with hook, used for writing Mandarin Chinese using the early draft version of pinyin romanization during the mid-1950s[14]

- IPA-specific symbols related to Z: ʒ ʑ ʐ ɮ

- U+1D22 ᴢ LATIN LETTER SMALL CAPITAL Z is used in the Uralic Phonetic Alphabet[16]

- Modifier letters ᶻ ᶼ ᶽ are used in phonetic transcription[15]

Ancestors and siblings in other alphabets

Computing codes

| Preview | Z | z | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER Z | LATIN SMALL LETTER Z | ||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 90 | U+005A | 122 | U+007A |

| UTF-8 | 90 | 5A | 122 | 7A |

| Numeric character reference | Z | Z | z | z |

| EBCDIC family | 233 | E9 | 169 | A9 |

| ASCII 1 | 90 | 5A | 122 | 7A |

- 1 Also for encodings based on ASCII, including the DOS, Windows, ISO-8859 and Macintosh families of encodings.

On the QWERTZ keyboard used in Central Europe the Z replaces the Y of the standard US/UK QWERTY keyboard as the sixth letter of the first row.

Other representations

See also

- Bourbaki dangerous bend symbol, U+2621 ☡ CAUTION SIGN

- 지: Korean letter for "ji" which sounds like "Z"

- Z with stroke, Ƶ

- Zed

- Zee

- Z flag

- Z (military symbol)

References

- 1 2 "Z", Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (1989); Merriam-Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged (1993); "zee", op. cit.

- ↑ One early use of "zee": Lye, Thomas (1969) [2nd ed., London, 1677]. A new spelling book, 1677. Menston, (Yorkshire) Scolar Press. p. 24. LCCN 70407159.

Zee Za-cha-ry, Zion, zeal

- ↑ Michael Chugani (2014-01-04). "又中又英——Mispronunciations are prevalent in Hong Kong". Headline Daily. Archived from the original on 2017-04-27. Retrieved 2017-04-26.

- ↑ Henry George Liddell; Robert Scott. "ζῆτα". An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ Ti Alkire & Carol Rosen, Romance Languages: A Historical Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 61.

- ↑ "asset". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ↑ "alphabet-e1309627843933.jpg". Archived from the original on 2016-04-23. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- ↑ George Eliot: Adam Bede. Chapter XXI. online Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine at Project Gutenberg

- ↑ "English letter frequencies". Archived from the original on 2010-06-09.

- ↑ "How Z-z-z-z-z-z Became Synonymous With Sleep and Snoring". 24 January 2020.

- ↑ "Why has the letter Z become the symbol of war for Russia?". The Guardian. 2022-03-07. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ↑ "Ivan Kuliak: Why has 'Z' become a Russian pro-war symbol?". BBC News. 2022-03-07. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ↑ Constable, Peter (2003-09-30). "L2/03-174R2: Proposal to Encode Phonetic Symbols with Middle Tilde in the UCS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- 1 2 West, Andrew; Chan, Eiso; Everson, Michael (2017-01-16). "L2/17-013: Proposal to encode three uppercase Latin letters used in early Pinyin" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-12-26. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- 1 2 Constable, Peter (2004-04-19). "L2/04-132 Proposal to add additional phonetic characters to the UCS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- ↑ Everson, Michael; et al. (2002-03-20). "L2/02-141: Uralic Phonetic Alphabet characters for the UCS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-02-19. Retrieved 2018-03-24.