Bell Church | |

View of the south and east faces | |

Shown within Turkey | |

| Location | Akhisar, Aksaray Province, Turkey |

|---|---|

| Region | Cappadocia |

| Coordinates | 38°17′55″N 34°08′7″E / 38.29861°N 34.13528°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Byzantines |

| Material | Red volcanic stone |

| Founded | 10-11th century |

| Abandoned | 14th century |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

Çanlı Kilise, meaning "bell church" or "church with a bell", is a Byzantine-era ruin site located about 15 km southeast of the city of Aksaray in Turkey.[1]: xix, 6 It consists of a large rock-cut settlement surrounding a prominent masonry church which lends its name to the whole site.[1]: 6 A rare masonry church from the historical region of Cappadocia, the church is one of the best examples of Byzantine masonry architecture in central Anatolia and is frequently cited in textbooks on Byzantine architecture.[1]: 17 Surrounding the church is a series of rock-carved houses carved into the south side of a hill (locally called Manastırtepe, or "monastery hill") over a distance of about one kilometer.[1]: 7 [2]: 302 Across the broad valley to the south, the peaks of Hasan Dağı are visible.[1]: 7 Çanlı Kilise is accessible by a road winding its way from Akhisar, 4 km to the west on the plain below, up through a rugged hilly area en route to Çeltek, which is 6 km north of Çanlı Kilise on the same road.[1]: 7

Based on its architecture and the styles of the paintings, Çanlı Kilise appears to primarily date from the 10th and 11th centuries.[2]: 302 It then went into a period of gradual decline before being abandoned altogether, perhaps as late as the 14th century.[2]: 302 There is a high concentration of large "courtyard" houses, indicating that it was a prosperous agricultural settlement or kome, with many affluent landowners.[2]: 302 Çanlı Kilise is the best-known example of these houses,[3] which probably represent mansions belonging to members of the landed military nobility in Cappadocia.[4] Today, some of its rock-cut complexes are used by local farmers as shelters for livestock.[1]: xix

Although now somewhat remote, the settlement at Çanlı Kilise was close to important sites during its heyday and thus would have been relatively well-connected.[1]: 8–9 Nearby Aksaray was then called Koloneia and served as an important crossroads for the region, while the major episcopal center of Mokissos lay a short distance to the southeast at the foot of Hasan Dağı.[1]: 8–9 Most importantly, at the old site at Akhisar (above the present-day village), there are traces of a fort which has been identified with the Hisn Sinan of contemporary Arabic sources.[1]: 8–9 Guarding the entrance to the Cappadocian highlands, Hisn Sinan was the most strategically important Byzantine fortification in the region, and one of the most critical defense points in all of Asia Minor.[1]: 8–9 Given how close the two were, the settlement at Çanlı Kilise must have been closely associated with the one at Hisn Sinan.[1]: 8–9

Name

The site is named after the prominent church ruin called Çanlı Kilise, meaning "bell church" or "church with a bell", supposedly because of a bell that once hung in its dome, which collapsed in the early 1950s.[1]: 6 Although some locals claim to have seen the bell before the dome collapsed, such a bell does not seem to have ever actually existed; nothing of the sort appears in early photographs taken of the church by Gertrude Bell in 1907.[1]: 6 The name may also be derived from the bell-like shape of the dome itself, or from the two-storied narthex's resemblance to a bell tower.[1]: 6 Another tradition once related by Greek villagers was that the name was because the sound of bells ringing could inexplicably be heard near the church.[1]: 6

The original Byzantine name of the site is unknown. However, taking into consideration that it was a royal Byzantine settlement and built in the years of Basil II, it’s possible that it could’ve been dedicated to him. The sheer size of the church, coupled with its location, and many other factors, indicate that it likely would’ve been dedicated to a Byzantine noble/royal. Some of the emperors of this time period were Nikephoros II Phokas, Constantine VIII, Constantine VII, and a much more likely link to the royal Phokas family. One suggestion is that it commemorated the victory of Basil II over Bardas Phokas.[5][6] In the interior of the Çanlı Church, It is decorated with frescoes about Jesus and his Apostles.[1]: 6

Settlement

The settlement at Çanlı Kilise follows a reverse S-curve along the southern slopes of two distinct plateau areas.[1]: 79 The eastern area is topped by a layer of limestone, with a lower layer of purplish-gray volcanic tuff.[1]: 79 This tuff layer is softer and the houses are mostly cut into it.[1]: 79 The area further west is lower and formed of harder gray tuff.[1]: 79 The northwestern end of the settlement is marked by a precipitous ravine.[1]: 79 At the northeastern end, below the modern road to Çeltek, is the old Byzantine road, cut into the bedrock with wheel ruts still visible.[1]: 79 Both ends of the former settlement appear to have been fortified with masonry structures at some point after it was originally built.[1]: 79

The reason why the settlement used rock-cut architecture instead of free-standing buildings is due to the nature of the building materials available locally.[1]: 3 Like elsewhere in Cappadocia, rock formations are mostly soft volcanic tuff and compressed ash that are easily carved but also easily weathered.[1]: 3 As a result, they were better suited for rock-cut architecture.[1]: 3

In some areas, the settlement is cut into layers of tuff that are directly above unstable layers of volcanic ash.[2]: 305 These areas have been heavily affected by erosion: some structures had collapsed, and in one case part of the rock formation containing the chapel separated from the rest of the complex and slid down the hill.[2]: 305

The settlement primarily consists of houses cut into the rock and arranged around a central courtyard.[1]: 7 About two dozen such courtyard houses are visible today, numbered Areas 1 through 23 from east to west.[1]: 79 Since a lot of the rock has collapsed, it's possible that the rock cutting was even more extensive.[1]: 79

Most of the larger courtyard houses have a series of dovecotes on an upper level, which originally would have been hidden behind the decorated portico façades; the portico façades have since collapsed, leaving the dovecotes exposed.[2]: 303 These dovecotes were there to provide dung for fertilizer, which would have been necessary for agriculture in a region lacking in rich soil.[2]: 303

Many of the houses appear to have been subdivided after they were originally built; as the prosperity of the settlement decreased, the houses came to accommodate multiple families.[2]: 303

In addition to the rock-cut structures and the Çanlı Kilise itself, there are also traces of a couple of other masonry churches: foundations of two above Area 12 and another near Area 2.[2]: 304 There are also a few areas with masonry walls, which served either as retaining walls to protect the courtyard houses from landslides or as defensive structures.[2]: 303 These appear to have been built after the courtyard houses themselves and were probably built during the period of decline when the inhabitants were threatened by raiders and the natural erosion of the site.[2]: 303

About 30 churches and chapels have been identified at the site.[2]: 303 The most common plan is the cross-in-square, like the Çanlı Kilise itself, but several have a cruciform or cross-shaped plan instead.[2]: 303

Areas 1-4

Area 1, at the northeastern end of the settlement, is the largest courtyard complex.[1]: 79 In addition to the main rock-cut house surrounding the courtyard, there are also multiple clusters of rock-cut rooms on the north and east.[1]: 79 These rooms were probably used for things like storage, agricultural production, or keeping livestock, and perhaps also as residences for servants or tenants.[1]: 79 There is also a rock-cut cemetery, with at least 16 tombs, in the northern area.[1]: 80

Further south, Area 2 (the area between Area 1 and the Çanlı Kilise) is filled with lots of rock-cut architecture, suggesting a high population density in this part of the settlement.[1]: 82–7 This is also true of Area 3, which includes the area immediately around the Çanlı Kilise and to the west.[1]: 82–7 Both areas have been affected heavily by landslides and collapses, however, making much of the rock-cut architecture inaccessible.[1]: 82–7

Just southwest of Area 1's courtyard house is the foundation of a freestanding masonry church, which was set on a level platform cut into sloping bedrock.[1]: 83 Further southwest, Area 2 includes two separate ranges of rock cuttings, one upper and one lower.[1]: 83 The lower part consists of two smaller courtyard units, each one surrounded by several smaller rooms that appear to have served agricultural functions.[1]: 83 The upper part contains one isolated cave with some built additions as well as three separate groups of rock-cut rooms.[1]: 84–5 One of them, located just below the cave, may represent the remains of another courtyard house, but is now mostly buried by landslide.[1]: 84 In the north of Area 2, there is a rock-cut church now mostly buried; it has an unusual layout (it's shaped like a trapezoid, and the axis changes multiple times within the structure), possibly because its position on a slope caused difficulties for its builders.[1]: 82–3 The only inscription found at the settlement was found in this church; its orthography suggests an early middle Byzantine period date.[1]: 84

As Area 3 contains the area immediately surrounding the Çanlı Kilise, it "should be critical to the interpretation of the role of the Çanlı Kilise within the settlement", but this area has been heavily damaged by landslide and collapse, making a lot of it inaccessible.[1]: 85 Immediately north of the Çanlı Kilise is a rock-cut façade that predates the church; the area behind the façade has collapsed, creating a large depression.[1]: 85 West of the Çanlı Kilise is a similar area "with depressions and fallen masonry, indicating that there was significant built and carved architecture in this area."[1]: 85–6 Just south of the Çanlı Kilise is a masonry wall, which may have been intended to protect the structures further downhill from landslides.[1]: 86 The upper level of these structures are severely eroded, while the lower level is what may have been "a small but elegant residential unit".[1]: 86 Further west are some more rock-cut rooms as well as a small rock-cut church.[1]: 86 Because of the landslides that have affected this area, it's not clear if the church was originally grouped with the Area 3 construction or if it was originally part of the now-collapsed Area 4 courtyard unit.[1]: 87

Area 4 includes two courtyard units, which are now interconnected.[1]: 87 One is now almost entirely caved-in and buried by landslides; it is just west of the rock-cut church in Area 3 and the two may have originally been grouped together.[1]: 87 The other, which is better preserved, faces north and contains a series of rectangular halls lined up along the façade.[1]: 87 The main hall is about 5x12 meters in size; it has a transept on the east side that connects to an adjacent hall, which then connects to an underground refuge down a long, narrow corridor.[1]: 87 Another entrance to this refuge is found in one of the rooms west of the main hall.[1]: 87

This refuge is one of several at Çanlı Kilise; they are similar to the so-called "underground cities" of Cappadocia, but smaller in scale.[1]: 88 This one, called Refuge 1, has only three or four levels, although there are several blocked corridors preventing them from being explored.[1]: 88 Refuge 1 also connects to the upper level of Area 5.[1]: 88

There is a second refuge accessed from Area 4 — on the eastern part of the upper level, there are three tunnels extending northward from what was probably a room in the northeast corner of the courtyard unit.[1]: 88 The easternmost tunnel is now blocked and inaccessible, while the other two connect to Refuge 2.[1]: 88 Refuge 2 appears to have originally been a separate courtyard house was open to the south, but was later buried by a landslide and then converted to an underground refuge.[1]: 89 Above ground in this area, there are also remains of masonry architecture.[1]: 88

Across the road south of Areas 3 and 4 is a large cemetery located on a triangular spur of land.[1]: 89–90 The southern part of this area has been significantly eroded, and many of the graves throughout the cemetery have been disturbed and the tombstones moved about.[1]: 90 The tombstones themselves are unique to this cemetery: they are shaped like sarcophagus lids, with the more elaborate ones having a stepped top.[1]: 89–90 Their shape resembles a common Seljuk tomb style, suggesting a late date for this cemetery (no inscriptions or other evidence of a specific date has been found).[1]: 90

Areas 5-8

Area 5 consists of a courtyard unit facing south, directly towards Hasan Dağı.[1]: 91 It has rooms on two levels; the lower level was converted to a stable at some point but is not currently used that way.[1]: 91 On the upper level is another entrance to Refuge 1.[1]: 91 On the east side of the courtyard is a cross-shaped church and another room with a similar layout.[1]: 91 Both rooms' domes are now fallen in, but they originally projected above the ground above.[1]: 91 The exposed part of the second room's dome was painted with red lines to imitate masonry construction.[1]: 92 Directly above the church, meanwhile, is a cemetery with 30 rock-cut tombs, some of which are cut into the church's dome.[1]: 91 Many of the tombs were apparently for children.[1]: 91

West of Area 5 (Area 5a) there was another courtyard unit that is now collapsed.[1]: 92 Only traces are visible now, and some of the rooms are too damaged to reconstruct their original layout.[1]: 92 There are remains of a tunnel that led to Area 5.[1]: 92 Below this area to the south is a partly-buried stone wall facing the road; its original purpose is unclear.[1]: 92

The courtyard house in Area 6 features fairly ornate architecture and has rooms on several levels.[1]: 92 It is now used as a stable, and the south-facing courtyard is partly enclosed by a modern rock wall.[1]: 92 The original layout of the upper part is now hard to discern because some parts have collapsed and other areas have later carvings or pigeonholes.[1]: 93 On the east side is a well-preserved cross-in-square church, whose exterior façade remains partially intact on the upper level.[1]: 93 The central naos is preceded by a narthex, although only one column survives to separate them today.[1]: 93 There are several cuttings for tombs in the floor of the naos.[1]: 93 The altar is set against the back wall of the apse, with curved benches on either side.[1]: 93 Above the dome of the church there is a cemetery with at least 10 rock-cut tombs.[1]: 93

Area 7 follows a similar plan to Area 6: it consists of a courtyard house facing south, with a large hall on the north side and a cross-in-square church on the east side.[1]: 94 This complex is now used as a stable for cows.[1]: 94 Like the church in Area 6, the naos of the Area 7 church is preceded by a narthex, with the altar attached to the back wall of the apse; there is also a full chapel to the south of the naos, elevated by three steps and with an altar against its own back wall.[1]: 94–5 The main hall extends horizontally along the entire front façade, and on the north side it is connected to three more rooms of different sizes.[1]: 94 Stairs once connected the main hall to an upper level which is now heavily collapsed in the center and has dovecotes on the sides.[1]: 95

Below Area 7 to the south is Area 7a, which consists of a few small rooms that may have been used as stables.[1]: 95

Area 8 has been heavily damaged by landslides and collapses.[1]: 95 Three distinct groups of rock-cut structures survive: the first, right next to Area 7, has two levels of rooms carved into the slope of the hill.[1]: 95 The upper level may have been centered around a small courtyard, but this area is now buried by landslide and the adjoining rooms have collapsed, making it hard to tell.[1]: 95 This complex may have included stables; niches in some rooms have carved holes in their corners which may have been used for tying up animals.[1]: 95

The second group contains several carved rooms, but except for one surviving chapel they are all too damaged by erosion to reconstruct.[1]: 95–6 The chapel is now also mostly buried.[1]: 95

Finally, the northernmost group in Area 8 consists of a central cluster of carved rooms that are now partly filled with dirt.[1]: 96 The central room was decorated with red and black paintings and both painted and carved Maltese crosses.[1]: 96 Access to several other rooms is at the back.[1]: 96 Just to the right of this central grouping, there are traces of a cross-shaped room, while to the left are a few other rooms.[1]: 96 There were probably originally two or more separate units here.[1]: 96

Areas 9-12

Area 9 consists of an isolated rock outcropping to the south that had various rooms cut into it.[1]: 96 Many of them are now collapsed, and most of them are fairly plain and lacking in architectural detail.[1]: 96 There are also a few rock-cut graves higher up.[1]: 96

To the south and west of Area 9, and west of Area 11, there is a steep dropoff, and access to the areas farther north is restricted to a narrow path that separates Areas 9 and 11 from the rest of the settlement.[1]: 96, 98 In this bottleneck there are remains of an old road cut into the rock, which may represent the main street running through the middle of the medieval village.[1]: 98 There are also remains of several masonry walls in the area, which may have been defensive structures built later in the settlement's history to control access to its northern part.[1]: 96

The main courtyard unit in Area 10 has rooms on two levels.[1]: 96 There are several large halls, as well as a stable and a chapel.[1]: 96–7 The rooms on the west side of the complex are more irregular.[1]: 97 Traces of a second distinct courtyard unit survive higher up, but a lot of it is now destroyed.[1]: 97 To the northwest, a large ravine separates Areas 10 and 12.[1]: 97

Like Area 9, Area 11 consists of an isolated rock outcropping standing across from most of the settlement.[1]: 98 There are several rooms on two levels, but they are all heavily eroded.[1]: 98 Area 11 in general is the most severely eroded part of the site, so much that a small rock-cut chapel on the northwest side has apparently separated from the main rock formation and slid down the hill.[1]: 9, 98 The chapel is tiny — its naos is just 1.58x2.08 m in size — and its narthex "has now almost completely disappeared; its remnants are suspended above a dropoff".[1]: 98

Comprising a single courtyard unit along with the foundations of two masonry churches further uphill, Area 12 is particularly important for interpreting the settlement's history because it shows signs of change over time.[1]: 98, 101 The rooms themselves resemble those found elsewhere throughout the site, indicating that Area 12 was also originally a residential unit.[1]: 101 However, the later addition of a chapel, apparently by converting a preexisting room, and the large number of churches (there are also two rock-cut churches within the complex) suggest that it was later converted into a monastery.[1]: 100–1 Moreover, some of the rooms were later converted to utilitarian or agricultural functions (a cistern was added in the main hall, and a manger in another room), and others were subdivided with rubble walls.[1]: 101 This indicates that the standard of living had declined significantly by the last phases of the site's occupation.[1]: 101 Finally, an underground refuge was added behind the main hall at some point, which may reflect that the site had become less secure by then.[1]: 101

The eastern rock-cut church in Area 12 has several fresco remnants throughout, as well as an unusual cross-shaped cutting some 40 cm across that may have once held a processional cross.[1]: 100 [2]: 304 One of the frescoes, perhaps dating from the 11th century, depicts the church's donors alongside a scene of the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace protected by an angel.[2]: 304 The human figures are lined up in a row and all have their hands raised in front of their hands in a gesture of prayer.[2]: 304 The Three Hebrews are depicted with halos and have orange flames below their feet.[2]: 304 The donor on the left appears to be female, while the one on the right is almost completely destroyed; neither one has flames beneath them.[2]: 304 This scene is normally represented in Byzantine art with the angel's wings extended over the Three Hebrews, but in this case the wings extend over the donors too.[2]: 304

Areas 13-23

Area 13 is a "well-organized" courtyard house that faces west-southwest and has three levels.[1]: 101 There is no church in this unit.[1]: 101 Most of the rooms are now partly buried, and the area on the south side of the courtyard has been so heavily damaged by collapse and landslide that its original layout is impossible to reconstruct.[1]: 101–3 Three main rooms open onto the portico on the east: a kitchen in the north, a small hall in the middle, and a cross-shaped room in the south.[1]: 102 The kitchen was originally square-shaped but was later expanded to the north, connecting to a storeroom with shelves on two walls.[1]: 102 The vaulted ceiling in the cross-shaped room has an opening to an upper room which was apparently added later.[1]: 102 On the north side of the courtyard was a stable, which was on a lower level.[1]: 102 The stable was later greatly expanded so that its original dimensions are barely distinguishable.[1]: 102 Above the stable was a tunnel connecting the storeroom with a small room further west; the tunnel has windows on both sides, opening onto both the courtyard and the stables.[1]: 102

Area 14 consists of various rooms carved into the side of a vertical rock face.[1]: 103 Many of them are poorly preserved.[1]: 103 This area includes a large basilica which is unique at the site.[1]: 103 The basilica consists of three aisles: a nave and two side aisles which were originally separated by columns but now only one column remains.[1]: 103 The nave is 11.40x3.55 m, and including the side aisles the total width increases to 7.15 m.[1]: 103 Area 14 also includes a large stable with well-preserved mangers.[1]: 103 Higher up above Area 14 (Area 14a) there was a large courtyard house, but this is now almost completely buried.[1]: 103

Area 17 appears to have been a monastery, specifically a form of metochion: a subsidiary monastery, typically intended to provide surplus production for the parent monastery.[7]: 124 It includes a church, refectory, various living quarters and other rooms, and an unusually large area dedicated to storage (typical of a metochion).[7]: 124 Further expansions to the storage space and a second refectory appear to have never been completed.[7]: 124 When the Area 17 monastery was abandoned is unclear, but it was probably at the same time as the rest of the settlement.[7]: 124

A church above Area 17, toward the northwestern end of the settlement, features some frescoes whose style suggests a tenth-century date.[2]: 304 In the apse is a Deesis scene, depicting the Christ enthroned between the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist.[2]: 304 There is a dedication here reading "τοû δούλου τοû Θεοû" ("of the servant of God"), but the donor's name is missing.[2]: 304

Outlying settlements

In addition to the main site of Çanlı Kilise, there are also a few other sites in the vicinity.[2]: 305 One of these is the "North Settlement", which is located about a kilometer to the north of Çanlı Kilise proper.[2]: 305 The North Settlement consists of the building foundations for a cruciform church and a rectangular building next to it, along with a small cemetery and an underground area to the northeast.[2]: 305 It was probably not inhabited at the same time as the main settlement: no glazed ceramics were found here, while some late Roman red-slip ware was found.[2]: 305 The buildings appear to date from the early Christian period, possibly the sixth century CE.[2]: 305 There is no evidence of rock-cut architecture here.[2]: 305 To the east of the church, though, there is a ridge of hard volcanic tuff which appears to have been used as a quarry for all the masonry churches at Çanlı Kilise.[2]: 305

About a kilometer east of Çanlı Kilise, on the slope of the next hill, is the East Settlement.[2]: 305 This may have been a monastery.[2]: 305–6 It consists of two larger churches and two smaller chapels, but most of this area is buried by landslides or damaged by erosion.[2]: 306

Finally, a third outlying settlement is located a bit further away, 3 km northeast of Çanlı Kilise on the road to Çeltek.[2]: 306 It includes three rock-cut churches and appears to date from the early-middle Byzantine period.[2]: 306

Church

The church at Çanlı Kilise appears to have been mostly done in three phases: first came the naos, or main central area; then the elongated narthex to the west of it; and finally the parekklesion, or funeral chapel, to the north of the naos.[1]: 17 It appears that the church was originally built as a free-standing structure located in front of a rock-cut façade, and then later the narthex connected the two.[1]: 17 The currently standing church also seems to have replaced an earlier structure on the site, possibly a chapel.[1]: 31 Because of its isolated location, the current church was never converted into a mosque and was instead eventually abandoned.[1]: 6

The church shares some architectural features with buildings from Constantinople, leading Richard Krautheimer to suggest that it was built by artisans from the capital.[1]: 17, 75 However, it was most likely built and decorated by local artisans.[7]: 152 While certainly influenced by Constantinopolitan styles — for example, it features a recessed-brick façade that would not become widely disseminated throughout the empire for another century[7]: 152 — the Çanlı Kilise also has a number of distinctly local elements as well, so the exact relationship with Constantinopolitan architecture is unclear.[1]: 75 For example, the thin lancet-shaped windows at Çanlı Kilise is a distinctively central Anatolian feature, contrasting with the larger and more complex windows found in churches from Constantinople, while the building's façade has more in common with churches from Syria or the Caucasus.[1]: 71–2, 74 The Çanlı Kilise's resemblance to buildings from the capital may be because its patron, who probably had connections with the imperial capital and may have been a member of the military elite, wanted to convey his/her prestige as a member of high society.[1]: 76

The church that survives today was probably originally built as a private chapel by the owners of either Area 3 or Area 4.[7]: 153 It would have been just one of several such churches in the village, alongside the two masonry churches at Area 12 and the one at Area 2.[7]: 153 While impressive today, the Çanlı Kilise was originally "a rather normal provincial church built quickly by unskilled locals."[7]: 153 The frescoes echo Constantinopolitan trends but are somewhat awkwardly executed, probably because the artist was used to working in rock-cut churches, which had different lighting and ceiling design to a freestanding masonry building like the Çanlı Kilise.[7]: 153

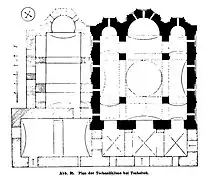

Phase I: the naos

The cross-in-square naos was the first part of the church to be built.[1]: 18 It was originally divided by four columns into nine bays, with apses connecting to the three bays on the east side.[1]: 18 The total area excluding the apses is 9.2 square meters.[1]: 18 The walls are about a meter thick.[1]: 18 The four columns supported the tall dome, which collapsed c. 1954; only two were still standing in 1906-7 when Hans Rott and Gertrude Bell visited, and today only one remains.[1]: 18

The walls of the naos are made from a rubble core, as was typical in central Anatolia, and faced with both brick and stone.[1]: 18 In some places, the external facing has fallen away to reveal the rubble beneath.[1]: 18 The stone cladding used was hard volcanic tuff, quarried just to the north of the settlement.[1]: 19 The brick cladding is unique to the naos; it is not used on other parts of the church.[1]: 18 The interior walls are primarily faced with ashlar, with brick being used only rarely here, and decorated with painted plaster.[1]: 24–5 The walls were strengthened with beams made from chestnut and juniper wood.[1]: 18 The foundation is made entirely of stone, partly cut directly into the bedrock.[1]: 18

Phase II: the narthex

The two-storied narthex on the west side of the church was a later addition; its northern part juts out a fair distance farther north than the naos.[1]: 27 It consisted of two distinct segments, north and south, which were both built at the same time and are connected by doors.[1]: 27 The narthex is entirely faced with stone, from the same quarry as the naos; no brick is used in this part of the church.[1]: 27 Only the western and southern façades of the narthex survive today, and the upper level of the north narthex has collapsed entirely, while the north half of the western façade is now partly buried.[1]: 27–8 The upper level of the south narthex appears to have been a fully functional area of the building, but the only way to enter it would have been to come through the now-collapsed north narthex; there are no traces of stairs in the south narthex.[1]: 30

An excavation by the Aksaray Museum in 1994 found 16 tomb cavities below the floor of the north narthex.[1]: 30–1 Many of the burials appear to be post-Byzantine, but some others appear to be from the same period as the settlement itself.[1]: 31 This indicates that while the north narthex was probably not originally intended to a burial site, it was already being used as one during the Byzantine period and then continued to do so long after the settlement itself was abandoned.[1]: 31 Most of the tombs had already been disturbed by the time of the museum's excavation.[1]: 30

At the southeast corner of the north narthex, there are traces of a wall carved directly into the bedrock and covered in a hard white plaster unlike the kind used elsewhere in the building.[1]: 30 There was apparently a large framed panel on the east side of the south wall, which was partly destroyed when the naos's foundation was cut into the bedrock.[1]: 30 On this panel are the partial remains of a fresco, showing a female with a halo tilting her head to the right on a pale blue background.[1]: 30 This fresco was later covered up by another one when the narthex was decorated.[1]: 30 The presence of the fresco indicates that something, apparently a religious structure, existed on the site before the church currently standing was built.[1]: 30 It may have been a chapel, which the current church replaced.[1]: 31

Immediately to the north of the narthex is a rock-cut façade, behind which is a separate series of rooms that by now have been almost completely buried by landslides.[1]: 31 This structure appears to predate the church, which must have been intentionally designed to be juxtaposed with the façade.[1]: 31 The narthex was not originally connected to the façade — they are separated by a small space, less than a meter — but later additions fully joined the two, probably around the same time as the parekklesion was built.[1]: 31 A partially surviving wooden beam here analyzed by dendrochronology suggested a date shortly after the year 1293.[1]: 31

Phase III: the parekklesion

The 4x8 square meter parekklesion was built directly onto the north side of the naos, blocking its north windows in the process.[1]: 32 Landslide and collapse have buried most of the parekklesion, and none of its exterior is visible today.[1]: 32 Like the narthex, its walls are made of a rubble core faced entirely with locally quarried stone, with no brick used.[1]: 32 The parekklesion was built using the already existing east wall of the north narthex as its west side, with one entrance on this side, while the north wall was placed just a short distance from the rock-cut façade.[1]: 32 Another entrance opened out into the narrow space between the parekklesion and the façade.[1]: 32 When it was first built, the parekklesion must have been fairly tall.[1]: 32 It was covered with a banded barrel vault, of which only the western part survives today.[1]: 32

There were four arcosolia in the parekklesion, two each on the north and south walls.[1]: 32 The two northern arcosolia had been buried by the 1990s when a full survey of the site was conducted, but they have since been uncovered by illegal excavations.[1]: 32 No evidence of burials within the arcosolia themselves survive, but the excavations also found a tomb cut into the floor in the main space of the parekklesion.[1]: 32 Like the north narthex, the parekklesion floor probably covers many more such tombs.[1]: 32

After the Phase III constructions, there is little evidence for the church's continued use, and it is unclear when it was finally abandoned.[1]: 33 Besides the tombs in the floors of the north narthex and the parekklesion, the main later addition is that a templon appears to have been added to the naos, enclosing its eastern bays.[1]: 33

View of the south and west faces

View of the south and west faces View of the west face, showing the narthex

View of the west face, showing the narthex Plan of the church, as drawn by Hans Rott

Plan of the church, as drawn by Hans Rott One of the photographs Gertrude Bell took of Çanlı Kilise in 1907, before the dome collapsed

One of the photographs Gertrude Bell took of Çanlı Kilise in 1907, before the dome collapsed

History of study

Early scholarship focused almost entirely on the eponymous church and mostly ignored the rest of the settlement.[1]: xix, 7, 10 When they did note the surrounding settlement they usually characterized it as monastic.[1]: 10 [2]: 301

Josef Strzygowski described the site in his Kleinasien, based on the notes of J.W. Smirnov; he dated the complex to the 10th or 11th century.[1]: 10

Hans Rott later visited Çanlı Kilise while heading from Akhisar to Çeltek; he characterized the site as "a great monastic settlement in the isolated mountain wilderness" and illustrated his account with a photograph and plan of the Çanlı Kilise itself as well as a sketch of the rock-cut church in Area 17.[1]: 10

Gertrude Bell visited the site on 12 July 1907, while en route to Aksaray after spending the morning at the Ala Kilise and the Karagedik Kilise in the Ihlara Valley.[1]: 11 She only stayed at the site for three hours, but in that time she drew up a plan and took several photographs as well as took many detailed notes, the most detailed account of the site until the 1990s.[1]: 11

After the outbreak of World War I, the site was left unexamined until 1956 when Michael Ballance visited the site and took notes and photographs.[1]: 12 Then Nicole Thierry visited in the 1960s and mentioned the church in several publications; she also described the surrounding rock-cut architecture in one of them.[1]: 12

A team led by Robert Ousterhout began an intensive survey (without any excavation) of the site in the summer of 1994.[1]: 14 In the first such survey of any Byzantine settlement in Cappadocia, the team focused on measuring and mapping, along with some minor cleanup in order to expose the original architecture.[2]: 301 An Electronic Distance Measurer (EDM) was used to record the site's topography, while architectural features were measured by hand and then entered into the EDM system.[1]: 14 This first summer was the first of four roughly three-week seasons taking place each summer.[1]: 14 The first season (1994) focused on the church itself, while later seasons focused on the surrounding settlement.[2]: 301

Later that fall, illegal excavation in the north narthex of the church revealed "mummies" (probably peasant burials from the 1700s or 1800s), prompting the Aksaray Museum to undertake a "rescue excavation" of the north narthex.[1]: 14 This excavation unearthed many more tombs cut into the narthex floor.[1]: 14

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 Ousterhout, Robert (2005). A Byzantine Settlement in Cappadocia. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 0-88402-310-9. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 Ousterhout, Robert (1997). "Survey of the Byzantine Settlement at Çanh Kilise in Cappadocia: Results of the 1995 and 1996 Seasons". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 51: 301–6. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ Howard-Johnston, James (2020). "Introduction". In Howard-Johnston, James (ed.). Social Change in Town and Country in Eleventh-Century Byzantium. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-884161-6. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ↑ Öztürk, Fatma Gül (2017). "Transformation of the "Sacred" Image of a Byzantine Cappadocian Settlement". In Blessing, Patricia; Goshgarian, Rachel (eds.). Architecture and Landscape in Medieval Anatolia, 1100-1500. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 144–6. ISBN 978-1-4744-1130-1. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ↑ Robert G. Ousterhout. "Development of Regional Styles II: Middle Byzantine Anatolia". Retrieved 2019-09-09.

- ↑ Ousterhout, Robert G.; Ousterhout, Robert (1 April 2023). Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands. Oxford University Press. p. 443.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Cooper, J. Eric; Decker, Michael J. (2012). Life and Society in Byzantine Cappadocia. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-36106-5. Retrieved 2 December 2021.